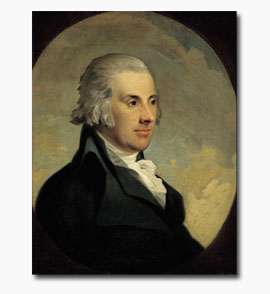

Edward James Eliot: Abolition and Reform

As his faith grew stronger and deeper, so did Edward James' ties to reformation and charitable work. Already well established in the work of parliamentary reform, he became an active supporter of the movement to abolish the slave trade and improve the lot of the African people in general. The great crusade of the Slave-Trade Abolition movement (as led by Wilberforce) began in earnest in 1787, and (being the year after Harriot's death) Edward James was in the perfect position, both physically and mentally, to immerse himself in the necessary work. In the last months of 1787, London papers were excitedly reporting meetings of Parliament Ministers and notable men at Mr. Wilberforce's house, No. 4 Old Palace Yard. Attendance was recorded of Mr. Eliot, Mr. Addington and the Bishop of Lincoln (among others), but Edward James' actions were not confined to this one great cause, and he willingly joined himself to his friend's other great mission: Social Reform.

In this same pivotal year, Edward James encouraged and joined Wilberforce in the formation of the "Association for the Discouragement of Vice". (Being so close to the Prime Minister, as well as holding the posts of a Lord of the Treasury and King's Remembrancer of the Exchequer, he was a powerful asset to any cause he supported.) His name was also published in the list of donors and supporters to the Marine Society, a long-time charity which educated poor boys for a career at sea. He also subscribed to a volume of poetry by Mrs. Charles Smith called "Elegiac Sonnets". Far from being a mere indulgence of pleasure reading (though it's quite likely that Edward James did enjoy poetry, as a number of his family did at this time), this volume was written in debtor's prison and was the lady's soon-to-be-successful attempt to pay her husband's debts and free herself and her children.

By 1791, Edward James was well-known for his philanthropic views and association with reform efforts, and it was no surprise when he was elected to chair a House Committee on the question of Abolition. Similarly, when Henry Thornton and his friends formed the Sierra Leone Company, Edward James was one of the Directors. This was a company founded "to encourage trade with the west coast of Africa; and above all—not to suffer their servants to have the slightest connection with the Slave Trade; neither to buy, sell, or employ any one in a state of slavery, and to repress the traffic as far as their influence would extend." This work also included the formation of the Sierra Leone colony. Although it was later suggested that the directors had used this company to the good of their own pockets, these founders actually laid down a by-law at its formation stating that no director would receive any emolument whatever for his services. In contrast, they actually used their own money to support the work. It was a busy time for our hero, since his name was also admitted to the "Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge". These were two associations with which he would remain active until his death.

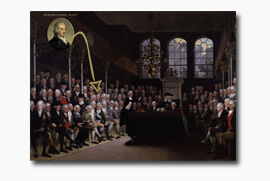

Edward James' work in the House continued just as active as his social work. Throughout the 1790s, his name appeared often in Parliamentary reports. He chaired a number of House committees, proving himself invaluable to his associates with his willingness to undertake these dull and unrewarding positions which most other MPs shirked. The issues discussed were things such as the Wine License Bill, Bribery and Corruption in Elections (again in conjunction with Lord Mahon), Voting Rights, etc. — never forgetting, of course, the continual committees on the Slave-Trade Abolition.

By 1793, Edward James' health was already delicate, on which account he resigned his post as Lord of the Treasury. In place of that, he was appointed a joint commissioner for the Affairs of India as a Joint Comptroller of the East India Board with Charles Jenkinson. This was the beginning of his serious involvement with that Asian country, a missions field that was obviously close to his heart. No doubt, too, this appointment must have been a great aid to his philanthropic work, since the post of Commissioner brought with it a salary of £2,500 a year.

As the years moved on, the Abolition movement continued, but things did not get very far. Bills were presented and voted on annually, but the result was always defeat. In 1793, the measure was lost by only eight votes. Britain was at war with France, and this caused fear and unrest to grow among the population. Concerns for their own safety over-shadowed people's concerns for the African slaves, and only very dedicated individuals persisted in the Abolition work as fervently as ever. In his support of Wilberforce and reform work, Edward James never wavered, but it was during this time of unrest that all of his characteristic kindness and sincerity was called upon to mediate between his two dearest friends. The Philanthropist and the Premier were at odds, and only their mutual friend was capable of bridging the proverbial gap. Wilberforce saw nothing greater or more important than his push for Abolition. Pitt saw the danger to the nation and the fear which such a move would cause during an economically perilous time. Edward James understood the rationale behind each man's point of view and managed to stand between both extremes, explaining to each friend that there was validity (with no intent of malice) in the other's cause.

Some difficulty arises while researching Edward James' activities during the 1790s, due to the fact that he and his two younger brothers were all known to London society as "Mr. Eliot." The problem is often trying to sort out just which Mr. Eliot is referred to, particularly between Edward James and his younger brother, John, also a very close friend of Pitt. One or the other of the brothers could usually be seen with the Prime Minister, but newspapers were not often careful to note which brother was actually in the report. One such example was the intriguing report in "The Times" on 12 Nov 1796:

"Mr. Eliot, who was in the carriage with Mr. Pitt on Wednesday when he went to Guildhall, was considerably hurt on the head by a stone thrown into the carriage."

Whether this report refers to Edward James or his brother, 1796 proved a very busy year for our Mr. Eliot. The annual presentation of an Abolition bill in Parliament ended in a defeat unlike any other, and feelings of "if-only" ran high among the friends. Wilberforce and many of his supporters (including, of course, Edward James) filled the benches of the House, but a handful of about a dozen of them favoured a trip to the opening night of a comic opera rather than staying to cast their vote. To the dismay of those present, the measure was lost by just four votes, and it would be a decade of even harder work before the Abolitionists would ever get that close a vote again.

In the midst of ever-failing health, this year saw two more important additions to Edward James' philanthropic plate — both of which began about the same time as the aforementioned parliamentary defeat. Firstly (together with Wilberforce, the Bishop of Durham and Sir Thomas Bernard), Edward James was listed as a founder of a later well-known charity called "The Society for Bettering the Condition and Increasing the Comforts of the Poor." (Sadly, the actual formation of this society took a little time to come about, and Edward James did not live to see the fruits of their labours.)

Secondly, Edward James assisted and supported Joseph Hardcastle's efforts to reform the East India Company. The HEIC was an old establishment full of corruption and personal greed. It basically ruled India as it deemed fit. Under the company's influence the country was effectually closed to any real missionary work, and Hardcastle (as a friend of Wilberforce) was ready to devote his fortune and talents on the reformation of the Company — the plan being to gain entrance for ten or twelve missionaries into the country. These men would teach English to the natives and spread the good news of the Gospel among them. India was ever on Edward James' heart, and this project suited him well. Sadly, it was too big a fight for just so few and the efforts proved fruitless, despite the additional backing of Wilberforce, Charles Grant and Henry Thornton. Speaking years later on this effort, Rev. John Morison noted that Hardcastle was assisted "perhaps more than all, by the Rt. Hon. E. J. Eliot, the beloved and accomplished brother-in-law of Mr. Pitt."

<< Previous Page • E.J. Eliot Home Page • Next Page >>

Although the following does not "move the story along", it would be appropriate here to take a glimpse at the privy nature of Edward James' political involvement with the highest powers. In this verbatim reporting of a private conversation between him and one of his closest friends, you can almost "see" him smiling at Mrs. Pretyman's reaction to his news. The following account was written by her in November of 1801.*

"In 1796 and 1797 things were critical for the Country, Bank of England, Naval Mutiny, etc. — And Mr Pitt (ever ready to sacrifice himself for what he thought the good of his Country) had serious thoughts of resigning his situation, hoping the French would make peace with another Minister rather than with him. We were at Buckden while this idea and consequent plan was upon the Tapis, but we heard constantly from Mr. Eliot. Details could not be mentioned in letters, and this plan was of a nature too delicate to be trusted to the Post. We knew nothing of it, therefore, till we went to Town (which happened to be two days after it was given up). Mr Eliot came to the Deanery an hour after our arrival. The Bishop was engaged with a person upon business, and Mr Eliot (afraid of not being in time for the House of Commons) told me the whole surprising story before the Bishop came up. He told me what I have related, of Mr. Pitt's idea and proposal, and that he thought he could make a very tolerable Administration without himself and a few others, so as to keep Fox and the Jacobins entirely out. Upon my asking eagerly ‘who could be found as Mr Pitt's Successor', Mr Eliot answered ‘Addington'.

‘Addington!' (exclaimed I instantly) Are you all mad?'

‘Oh no,' (said Mr. Eliot, smilingly), ‘Addington would do very well under the direction of Mr. Pitt — for a time — It would not do for ever, but it would do Mr. Pitt good to be out of office for a little while. . . . But you may make yourself easy, for the thing is not to be. Everything is now settled, and we are to remain as we are. The Storm is over.'

‘Does Addington know what was intended?' [asks Mrs. Pretyman]

‘Yes.'

‘Does the King know? Did it go so far as that?'

‘Yes. He certainly did not like the change, but what could he do when the present Ministers thought it necessary?'

‘Did Addington readily agree to the new arrangement?'

‘Certainly. How could he do otherwise at Mr. Pitt's request? He owes everything to Mr. Pitt, and Mr. Pitt would have directed had he taken the situation, so that he would not have been under great difficulties. Besides, I really do not think so ill of his abilities . . .'"

* Conversation transcribed in "The Younger Pitt: The Consuming Struggle" by John Ehrman.