Arthur Pringle (1877 - 1902)

Arthur was the second child and second son of Lionel Pringle and Charlotte Atkinson, known to family and friends as "Arthur".

Arthur's story is a short and sad one. He was remembered by his cousin, Eleanor Jauncey, in her memoirs as follows:

"Arthur had out distanced Jellicoe in many exams, and then he was killed in an accident, just as he reached the deck on coming up. It was a terrible loss to all the family and the Navy."

— Details about Arthur's childhood have not surfaced, but he did appear in two British censuses.

1891 Census: Arthur appears in Paddington as a Naval Cadet.

1901 Census: Arthur was serving on the HMS Camperdown (1st Class Battleship, Captain Alvin Coote Corry)

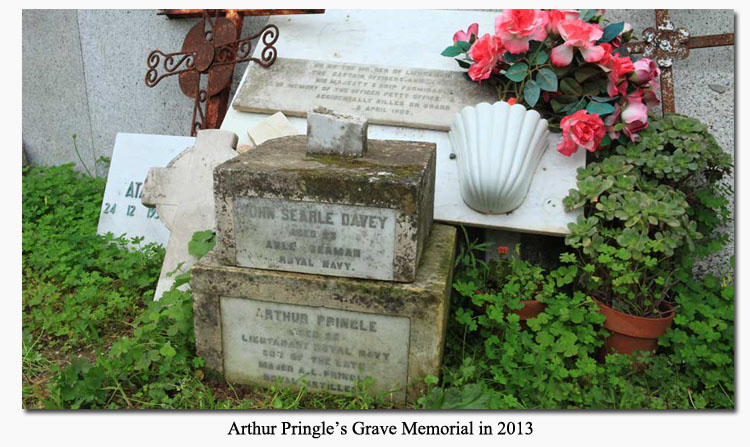

While researching Arthur Pringle, I was surprised (and pleased) to run across an online article published on an Italian news site in 2013. Since my Italian is non-existent, I had to translate the article with Google Translate, resulting in a rough but fascinating story. In short, an Italian gentleman discovered a discarded and mistreated tombstone in Olbia Cemetery. The inscription gave the names of two young men, John Davey and Arthur Pringle of the Royal Navy. The epitaph stated that they were accidentally killed on board the Formidable.

On seeing this memorial in such poor condition (broken and leaning against a wall), the gentleman was quite outraged at the disrespect shown by the citizens of Olbia to the memory of those buried in the local cemetery. He wondered how these two sailors happened to die so far from home and why they were buried there in Olbia, stating that the "eventual reconstruction" of those events would have to be left to historians — and how sad, he mused, would any family be to one day find his article and photo of the state of this poor grave, should Google ever index his words and make them searchable to any relatives who may wonder where Davey or Pringle was laid to rest.

Just one year after that gentleman wrote his article (which is now no longer online), I stumbled across it via . . . you guessed it! Google had made his wish come true. Thanks to this man's work, it was possible to see the long-forgotten memorial to our own Lieutenant Arthur Pringle. And for those interested in the particulars, the following articles give accounts of Arthur's death and funeral.

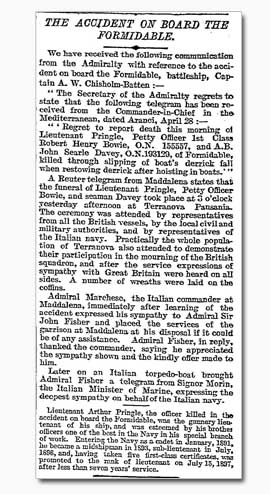

— "The Times" 30 Apr 1902, page 2:

THE ACCIDENT ON BOARD THE FORMIDABLE.

We have received the following communication from the Admiralty with reference to the accident on board the Formidable, battleship. Captain A.W. Chisolm-Batten:—

"The Secretary of the Admiralty regrets to state that the following telefram has been received from the Commander-in-Chied in the Mediterranean, date Aranci, April 28:—

"Regret to report death this morning of Lieutenant Pringle, Petty Officer 1st Class Robert Henry Bowie, O.N. 155557, and A.B. John Searle Davey, O.N. 193129, of Formidable, killed through slipping of boat's derrick fall when restowing derrick after hoisting in boats."

A Reuter telegram from Maddalena states that the funeral of Lieutenant Pringle, Petty Officer Bowie, and seaman Davey took place at 3 o'clock yesterday afternoon at Terranoca Pausania. The ceremony was attended by representatives from all the British vessels, by the local cicil and military authorities, and by representatives of the Italian navy. Practically the whole population of Terranoca also attended to demonstrate their participation in the mourning of the British squadron, and after the service expressions of sympathy with Great Britain were heard on all sides. A number of wreaths were laid on the coffins.

Admiral Marchese, the Italian commander at Maddalena, immediately after learning of the accident expressed his sympathy to Admiral Sir John Fisher and placed the services of the garrison at Maddalena at his disposal if it could be of any assistance. Admiral Fisher, in reply, thanked the commander, saying he appreciated the sympathy shown and the kindly offer made to him.

Later on an Italian torpedo-boat brought Admiral Fisher a telegram from Signor Morin, the Italian Minister of Marine, expressing the deepest sympathy on behalf of the Italian navy.

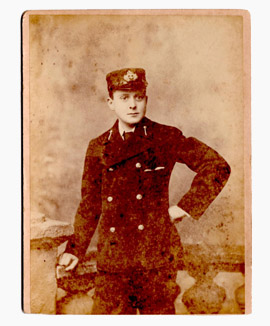

Lieutenant Arthur Pringle, the officer killed in the accident on board the Formidable, was the gunnery lieutenant of his ship, and was esteemed by his brother officers one of the best in the Navy in his special branch of work. Entering the Navy as a cadet in January, 1891, he became a midshipman in 1893, sub-lieutenant in July, 1896, and, having taken five first-class certificates, was promoted to the rank of lieutenant on July 15, 1897, after less than seven years' service.

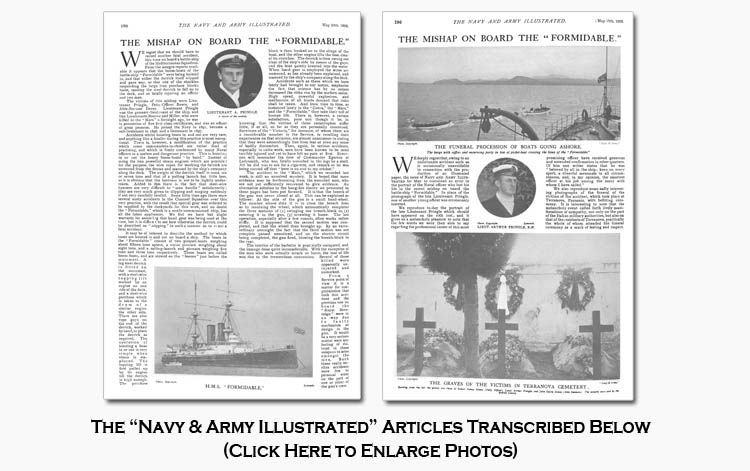

— "The Navy and Army Illustrated" 10 May 1902, page 190:

THE MISHAP ON BOARD THE "FORMIDABLE."

We regret that we should have to record another fatal accident, this time on board a battle-ship of the Mediterranean Squadron. From the meagre reports available it appears that the boom-boats of the battleship “Formidable” were being hoisted in, and that either the derrick itself slipped and gave way, or that one of the shackles suspending the large iron purchase blocks burst, causing the steel derrick to fall on to the deck, and so fatally injuring an officer and two men.

The victims of this mishap were Lieutenant Pringle, Petty-Officer Bowie, and Able-Seaman Davey. Lieutenant Pringle was the gunnery-lieutenant of the ship, and like Lieutenants Bourne and Miller, who were killed in the “Mars” a fortnight ago, he was in possession of five first-class certificates, and was an officer of great promise. He joined the Navy in 1891, became a sub-lieutenant in 1896, and a lieutenant in 1897.

Accidents whilst hoisting boats in and out are very rare, and anything like a fatality during this practice is most exceptional. There is, however, a modification of the practice which some commanders-in-chief are rather fond of practicing, and which is freely condemned by many Naval officers as a useless and dangerous practice. This is hoisting in or out the heavy boom-boats “by hand.” Instead of using the two powerful steam engines which are provided for the purpose, the wire ropes for working the derrick are unwound from the drums and manned by the ship’s company along the deck. The weight of the derrick itself is some six or seven tons and that of a pulling launch but little less, so it is obvious that the business is not to be lightly undertaken. Added to this there is the fact that steel-wire hawsers are very difficult to “man handle” satisfactorily; they are very much given to slipping and surging suddenly if not very carefully tended. Some little time ago there were several nasty accidents in the Channel Squadron over this very practice, with the result that special gear was ordered to be supplied by the dockyards for this work, and no doubt the “Formidable,” which is a newly-commissioned ship, has all the latest appliances. We feel we have but slight warranty for assuming that hand gear was being used at the time, but it is difficult to see how otherwise the derrick could be described as “slipping” in such a manner as to cause a fatal accident.

It may be of interest to describe the method by which boats are hoisted in and out on board a ship. The boats in the “Formidable” consist of two picquet-boats weighing about fifteen tons apiece, a steam pinnace weighing about eight tons, and a sailing-launch and pinnace weighing five tons and three tons respectively. These boats are called boom-boats, and are stowed on the “booms” just before the mainmast. A big steel derrick is fitted on the mainmast, with a steel-wire topping lift worked by an engine on one side of the deck, and a steel-wire purchase which is taken to the drum of a similar engine the other side. There are also rope guys on the end of the derrick, worked by hand, to place the derrick as required. The operation of hoisting a boat in or out is very simple when steam is employed. The topping lift is first pulled up by its engine till the derrick is high enough. The purchase block is then hooked on to the slings of the boat, and the other engine lifts the boat clear of its crutches. The derrick is then swung out clear of the ship’s side by means of the guys, and the boat quietly lowered into the water. When hand gear is employed the wires are unwound, as has already been explained, and manned by the ship’s company along the deck.

Accidents such as these which we have lately had brought to our notice, emphasize the fact that science has by no means decreased the risks run by the modern sailor. High speed, powerful explosives, and mechanism of all kinds demand that risks shall be taken. And from time to time, as instanced lately in the “Cobra,” the “Mars,” and the “Formidable,” they take their toll of human life. There is, however, a certain satisfaction, poor one though it be, in knowing that the victims of these catastrophes suffer little, if at all, so far as they are personally concerned. Survivors of the “Victoria,” for instance, of whom there are a considerable number in the Service, in recalling their experiences on that occasion, are almost unanimous in stating that they were astonishingly free from fear or even any sense of bodily discomfort. Then, again, in serious accidents, especially in cable work, men have been known to be most terribly injured and yet to have felt no pain at first. Everyone will remember the case of Commander Egerton at Ladysmith, who was fatally wounded in the legs by a shell. All he did was to ask for a cigarette, and remark as he was being carried off that “here is an end to my cricket.”

The accident to the “Mars,” which we recorded last week, is still an unsolved mystery. It is hoped that more evidence may be forthcoming from the wounded men, who are not yet sufficiently recovered to give evidence. An alternative solution to the hang-fire theory we presented in these pages has been put forward. It is that the breech of the gun was never closed at all. This can be explained as follows: At the side of the gun is a small hand-wheel. The number whose duty it is to close the breech does so by revolving the wheel, which automatically completes the three motions of (1) swinging the breech-block to, (2) entering it in the gun, (3) screwing it home. The last operation, especially after a few rounds, often works rather stiffly. It is supposed that the second motion was completed, and that the wheel then brought up. By an extraordinary oversight the fact that the third motion was not complete passed unnoticed, and on the electric circuit being completed, the gun fired, blowing the breech-block to the rear.

The interior of the barbette is practically uninjured, and the damage done quite inconsiderable. With the exception of the men who were actually struck or burnt, the loss of life was due to the tremendous concussion. Several of those killed were apparently uninjured and unmarked.

From a Service point of view it is a matter for congratulation that both this accident and the previous one on board the “Royal Sovereign” were in no way due to faulty mechanism or design in the gun. It would be very serious matter were any feeling of distrust in these weapons to arise amongst the men. Both these really terrible accidents were due to personal error on the part of one or other of the gun’s crew.

— "The Navy and Army Illustrated" 17 May 1902, page 196:

THE MISHAP ON BOARD THE "FORMIDABLE."

We deeply regret that, owing to an unfortunate accident such as is occasionally unavoidable in connection with the production of an illustrated paper, the issue of "Navy and Army Illustrated" for May 10 contained an error in the portrait of the Naval officer who lost his life in the recent mishap on board the battleship “Formidable.” In place of the photograph of the late Lieutenant Pringle, one of another young officer was erroneously inserted.

We reproduce today the portrait of the late Lieutenant Pringle which should have appeared on the 10th inst., and it gives us a melancholy pleasure to note that the few words we were then able to say regarding the professional career of this most promising officer have received generous and extended confirmation in other quarters. Of him one writer states that he was “beloved by all in the ship; keen on every sport, a cheerful messmate in all circumstances, and, in my opinion, the smartest officer at his job among the many with whom I have sailed.”

We also reproduce some sadly interesting photographs of the funeral of the victims of the accident, which took place at Terranova, Pausania, with befitting ceremony. It is interesting to note that the melancholy event called forth lively manifestations of sympathy, not only on the part of the Italian military authorities, but also on that of the residents of Terranova, practically the whole of whom attended the funeral ceremony as a mark of feeling and respect.