Edward James Eliot: Visit to France

Despite the unrest of the British political scene in 1783, Edward James and William Pitt managed to find enough time for a visit to France. Originally, the two friends planned the trip by themselves, intending to spend a few weeks in Rheims to improve their poor knowledge of the French language before continuing on for a visit to Versailles and Paris. They arranged to meet at Kingston Hall in Dorsetshire, the home of their mutual friend, Henry Bankes. This rendezvous was set to take place in the first days of September, with the pair setting off from there to journey into London and then on to the continent. Wilberforce discovered their plans and wrote to Pitt, enquiring just when they were setting out, stating that he intended to join them. Judging from fragments of surviving letters, Wilberforce was not reliable or punctual when it came to outings with his friends, and Pitt was wary of the possible consequences of this new arrangement thrust upon the sojourners. He informed Edward James of this change, assuring him that this had been agreed to on one condition: "I wrote to him [Wilberforce] that if he is not at Bankes's the 1st of September or in London the 2nd or 3rd, he will have no chance of going with us."

Actually, Pitt's rephrasing of his words to Wilberforce "lost something in the translation", as they say, and the original is worth including here as an illustration of the frank correspondence between the trio:

Burton Pynsent, Saturday, August 22, 1783

Dear Wilberforce,

I hope you have found benefit enough from your inland rambling, to be in perfect order now for crossing the seas. Eliot and I meet punctually at Bankes's the 1st of September, and in two days after shall be in London. Pray let us see you, or hear from you by that time, and do not verify my prophecy of detaining us a fortnight, and jilting us at the end of it. We shall really not have a day to lose, which makes me pursue you with this hasty admonition. Adieu. Ever yours,

W. Pitt

Obviously, both Pitt and Eliot well understood their friend and were doing their utmost to make the trip to the Continent a pleasant and successful one. Wilberforce must have taken Pitt's admonition to heart, since he managed to get himself to the rendezvous with enough time for the trio to even spend a few days together before arriving in Canterbury on September 11th. Even with a "heavy sea", they embarked from Dover on the following day, arriving at Calais later the same afternoon. Despite the good beginning to their holiday, however, things soon fell apart for the young adventurers from across the Channel.

Social etiquette of the 18th century demanded that a stranger present letters of introduction while on a holiday of this kind, but the three friends reached the French shore colossally ill-prepared. Not one of them had ever left England before, and each had trusted to the others for an introduction into high society. On discovering their mistake shortly before their departure, the best that they could produce was a letter (obtained through their friend, Mr. Robert Smith, and written by a Huguenot banker and merchant by the name of Peter Thelluson) to a Monsieur Coustier of Rheims. Relieved with what appeared to them to be a relatively easy solution to their problem, the young men set out for that city and (upon their arrival) engaged rooms at a local inn. They presumed this Monsieur Coustier to be a man of some consequence in the city; and, on the following day, dressed in their best, the trio set out for his establishment. What disappointment ensued when they arrived at a small shop to find him nothing more than a "veritable epicier" (or "grocer") standing behind a counter serving figs to his clientele! Wilberforce's description of this moment is quite entertaining:

". . . the day after our arrival [we] dressed ourselves unusually well, and proceeded to the house of a Mons. Coustier to present, with not a little awe, our only letters of recommendation. It was with some surprise that we found Mons. Coustier behind a counter distributing figs and raisins. I had heard that it was very usual for gentlemen on the continent to practise some handicraft trade or other for their amusement, and therefore for my own part I concluded that his taste was in the fig way, and that he was only playing at grocer for his diversion; and viewing the matter in this light, I could not help admiring the excellence of his imitation."

As candid and polite as Monsieur Coustier proved himself to be, he was certainly not able to introduce the aspiring politicians to any local men of consequence or position, as he informed them that he could claim not even one acquaintance among the gentry. The deflated trio returned to their rooms and spent (as Wilberforce described it) "nine or ten days without making any great progress in the French language, which could not indeed be expected from us, as we spoke to no human being but each other and our Irish courier." Not wanting to leave in despair (after weeks of anticipation regarding the "vast pleasure" their little ramble promised), the Englishmen approached the poor epicier and "prevailed on him to put on a bag [wig] and sword and carry us to the intendant of the police, whom he supplied with groceries. This scheme succeeded admirably."*

While Wilberforce may have felt that the whole scheme worked out well (and that the intendant was "extremely civil"), in truth, the intendant of the police was quite suspicious of the ill-prepared Englishmen. He was so convinced that they were British spies that he reported their presence to the Archbishop, Abbe de Lageard, by recommending an official investigation and stating that the young men were "of very suspicious character. They are in wretched lodgings, they have no attendants, yet their courier says that they are ‘grands seigneurs', and that one of them is the son of the great Chatham. But it is impossible! They must be des intrigants."

Fortunately for the unsuspecting visitors, Abbe de Lageard had been in England himself, and responded to the request for an investigation with his astute observation that the younger sons of the English nobles were not always wealthy. Instead of sending out an official investigator, he insisted on visiting the trio himself. Just how happy they were to find a new friend in Lageard can only be imagined, after their dismal days alone in their "wretched lodgings", and the following weeks amply repaid the gentlemen for their lonely existence at the inn. Now, instead of eating their meals alone, they dined at Lageard's house, talking for five or six hours after dinner. They enjoyed the "best wine the country could afford" and compared political institutions of the two countries. Pitt's French was quickly improving, as he "had a quick ear for all but music". Sadly for us, no one seems to have recorded if this visit proved helpful in the same respect for either Edward James or Wilberforce.

When the Archbishop of Rheims returned to town at the end of the month, he arranged for the three gentlemen to dine with him, and it may be this amusing occasion which was described some time later:

"Supping one evening at the house of one of the gentry, they observed a large space left vacant in the middle of the table, which was in other parts covered with delicacies. The party was large, and a mysterious smile and whisper circulated amongst the guests. Presently the door of the apartment flew open, and two servants entered, bearing between them a huge dish of roast beef, which was put down with an air of importance in the vacant place [having been prepared just for the British guests]. The beef was cut, and the Englishmen invited to fall to. It proved to be almost raw, and they could none of them touch it. As to Mr. Pitt, he never ate any meat which was not thoroughly well done. The French appeared much disappointed, and it was clear they thought their guests were ashamed to display their national tastes before strangers."

On the twelfth of October, the trio set out for Paris (now appropriately armed with ample letters of introduction). Because the King had taken his entire court to Fontainebleau, the whole city was almost completely emptied of any French, with only British tourists being "quite in possession of the town". Edward James and his friends spent a week in Paris, doing little but seeing the sights, before they followed the French nobles to Fontainebleau. There, they were presented to Louis XVI and his famous queen, Marie Antoinette. The story of the friends' debut at Rheims had travelled before them, now well known to every Frenchman at court. The queen herself was so amused by the tale that she could not refrain from then on, if in company with Mr. Pitt at any party or gathering, to inquire whether he had heard from "his friend the epicier".

As a result of making such a good impression on the French monarchs, the three young men were introduced to many great statesmen and literaries. Together they attended numerous suppers and card parties, visited theatres and the opera, and played billiards. Pitt even spent a day stag hunting, while Edward James and Wilberforce opted for a more subdued entertainment and set off in a chaise to attend the Court.

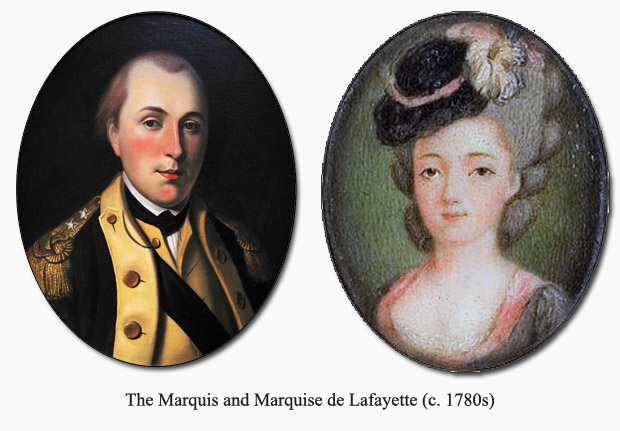

Always ready to combine business with pleasure, Pitt did not let the remainder of this sojourn on the continent slip by without making some advancement in political connections. After spending so much time in their private rooms at Rheims, the trio was doing a fine job of making up for lost time. On their arrival in Paris, Pitt had requested an introduction to the renowned hero (and ardent abolitionist), the Marquis de Lafayette, and was immediately invited to dinner at the well-known house on Rue de Bourbon. Lafayette was recently returned from America and still exulting in the termination of hostilities between that new country and Great Britain (the peace treaty having been signed at the beginning of September, just as the three young gentlemen were setting out on their holiday). Critics of the great French General were quick to raise an eyebrow at his choice of guests, having so recently been "enemies", but neither Lafayette nor Pitt was the type to worry about criticism of this sort. While conversing with his host, Pitt expressed his "warm desire" for an introduction to the prominent American statesman, Benjamin Franklin.

For the purpose of making the desired introduction, Lafayette immediately sent off invitations for a party, to take place the following evening. The impromptu gathering stood as one of the highlights of the trio's French holiday (not to mention an event that remained a popular topic in conversation, in both France and England, for decades to follow). Lafayette kept company with many eminent citizens of both France and the new country across the ocean, and the "Monday night dinners" given by the Marquis and Marquise at their home on Rue de Bourbon were remarkable social events in Parisian society. Lafayette planned an "American Dinner" for the night of 20 Oct 1783, and it turned into one of the most memorable of these intimate entertainments to ever be given by the General. Eighteen distinguished individuals sat down to dinner, the guest list including Benjamin Franklin, the Vicomte de Noailles, the Comtesse de Boufflers, George Henry Fitzroy (later 4th Duke of Grafton), John Jeffreys Pratt (later 1st Marquess Camden), and, of course, Messrs. Pitt, Wilberforce and Eliot. What a change from the first dinners in France, just six weeks earlier, when the three disappointed travellers ate their simple dinners in those "wretched lodgings" at Rheims!

Following his customary behaviour of remaining in the shadows, not one mention of Edward James seems to have been recorded in relation to this illustrious gathering, but a few scraps survive in reference to his two friends. Pitt was certainly the man whom all the French gentry and politicians wished to meet, but Wilberforce made a more favourable impression. Franklin extended "hearty" greetings to that young parliamentarian who had so openly opposed the war with America (particularly in his brilliant speech of 22 Feb 1782). In fact, it was Wilberforce's fellow M.P. for Hull, David Hartley, who had just signed the Treaty of Paris (ending the hostilities between Britain and America) along with Franklin and numerous American politicians, so the elderly American statesman was well-disposed to the young representative from Hull. These greetings were, naturally, welcomed by Wilberforce, but he was himself more intrigued by Lafayette, calling him a "pleasing enthusiastical man" and his wife "a sweet woman". He observed what a singular position the Marquis occupied, a seemingly perfect representative of democracy in the very presence of the French monarchy.

Pitt's impression of the Marquis was not so favourable, since the two men differed so acutely in political opinions. The one fact recorded about Pitt's conversation at this remarkable dinner was recounted some years later by the Marquis himself, when he remarked that the young Pitt told him "that he had too much democracy in his principles for him". Obviously, the feeling was mutual, as Lafayette considered Pitt to be no friend of the British people (despite his great majority in Parliament and the confidence of the public), he and his ministers having contributed "more or less to increase the influence of the Crown".

This great dinner was the last excitement for the three English travellers, since Pitt was called back to London just two days later. After spending six weeks abroad, the trio returned to their native shore, "better pleased with their own country than before they had left it". This was the only time that Edward James Eliot ever left England.

<< Previous Page • E.J. Eliot Home Page • Next Page >>

*This incident with Monsieur Coustier remained a tale that Wilberforce enjoyed the rest of his life, often relating it to friends and acquaintances "with much humour." More than forty years later, he recounted the meeting (several times, actually) to Harford, who then published them in his Recollections of William Wilberforce. Time had had its effect on the great man's memory, though, and his tale varied in some particulars from the letter he had written to Henry Bankes in 1783 (which is quoted above), in which he described the events of the French ramble in great detail. Since it seems most likely that the 1783 version would be the most accurate version, it is from there that the majority of Monsieur Coustier's part in this tale was taken for this page.