Edward James Eliot: Engagement and Marriage

On his return from France, Edward James threw himself into his political activities. Great changes came in December 1783, when the Fox-North coalition fell and the King named Pitt as Prime Minister. Once again, Edward James was appointed a Lord of the Treasury, and this time he would hold the position for almost ten years. At the beginning of the new year, his father received a peerage, being created Baron Eliot of St. Germans. Also at this time, Edward James was chosen M.P. for Liskeard — his father's most powerful seat.

More great changes were in store for our young hero. Not only was his political career moving ahead, but so were matters in his personal life. At some point during this period, Edward James became briefly engaged to Miss Mary Palmer, the niece of Sir Joshua Reynolds. That attachment was broken off (presumably mutually, as the families remained on the closest terms), and Edward James continued on as a most socially eligible bachelor.

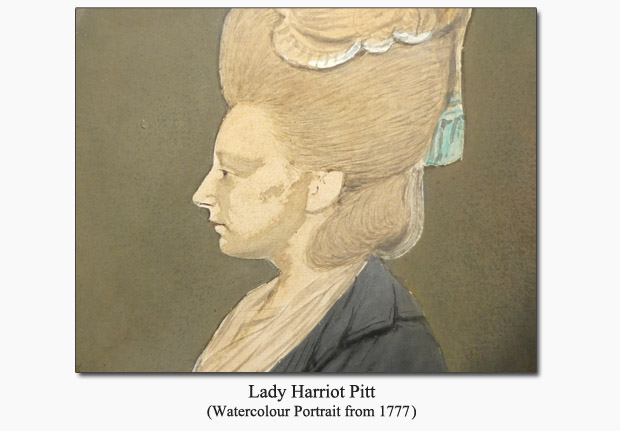

During their days at Cambridge, Edward James had become one of William Pitt's closest friends, the two of them dining and staying together more often than not. This meant that Edward James was thrown together with Pitt's younger sister, Harriot, whenever she was in town and staying at her brother's house in Downing Street. The first mention of "Mr. E" in Harriot Pitt's surviving letters occurs at the end of May 1781 (two years before the French affair), when he was among a few friends listed as arriving for dinner. By 1783 (a full two years before they married), Edward James was regularly mentioned in these letters as a close friend of the family.

Harriot was considered one of the most fashionable young women of her day, the same age as her brother's best friend, and often seen in the company of her brother and his best friend. It was only natural that their names would soon be linked in the gossip columns, and – in January of 1785 – the first London papers reported a "sure" match between Mr. Eliot and Lady Harriot. As has always been (and is still often) the case, the newspaper reports were incorrect and premature, as no serious attachment between the couple was formed until March. On April 2nd, Edward James wrote to his father at Port Eliot to inform him of the engagement, stating, "I am to acknowledge to you my attachment to Lady Harriot Pitt, which has been so long attributed to me by report, which was indeed attributed much sooner than there was any ground for it, and which was some time ago supposed to have proceeded much farther than you may readily suppose it has yet gone."

As happy as Edward James was about this happiest of events, the news did not bring joy to Lord Eliot. Not unreasonably (though quite unromantically), he wished his oldest son and heir to marry a woman of some fortune. The Eliot estate was just blossoming into the flourishing property it would become in future decades, and the father hoped that the son would follow in his footsteps by marrying a woman who could swell the family coffers enough to continue actual growth of the burgeoning estate. Instead, Edward James had chosen a very poor young lady with no dowry. Granted, she was the daughter of an Earl, but this single claim to social status was only due to the political genius of her late father — a man who died so far in financial arrears that Parliament actually had to step in to pay his debts, and whose surviving widow and children forever struggled to make ends meet. Neither Harriot's mother nor her brother (whose political career was beginning to achieve success but whose finances were to remain always "in the red") had any money to settle on her, so Harriot was certainly not the "catch" that Lord Eliot had hoped for in a daughter-in-law.

By August of 1785, the strain between father and son came to a head, and Edward James travelled to Port Eliot to discuss his upcoming marriage with his father in person. Writing to Harriot on the evening of the 31st, he recounted the disturbing event:

"My dearest Love, — I have had a conversation with my Father this morning, upon the whole certainly a melancholy one. It began with his telling me with a good deal of agitation that he already had annual expenses beyond his annual income, that therefore it was altogether out of his power to give me any assistance — that he almost desponded of his own affairs and thought it little less than absolute ruin for us to think of going on on the present plan in the present circumstances."

Lord Eliot advised the pair to wait until the death of an elderly uncle (Lord Nugent), at which time Lord Eliot would come into a large sum of money, thereby finding himself in a position to help his son as he would wish. Horrified at this thought of delay, Edward James assured his "dearest Dear Harriot" that none of his father's reasoning had at all entered his mind. After all the discussion and no opinions having been altered, Edward James travelled back to his father's house in Spring Gardens (London). From there, on September 8th, he wrote again to Port Eliot, informing his father that the marriage was to go ahead as planned:

"It then only remains for me to entreat your pardon and forgiveness, and to pray you will from this moment consider the thing as done . . . as it is I am, I do assure you, most deeply distressed at the manner in which you feel and think of the event. I believe you do not doubt that I do so. It wounds most deeply the happiness and satisfaction which I should otherwise have felt of every kind at this connection . . .It is no small additional anxiety to me to reflect on the inconveniences of a different kind which you feel yourself in, but which as some consolation to myself, it is my firmest resolution never to multiply or augment."

Edward James married his dear Harriot at William Pitt's house in Putney just sixteen days later, and the couple never did add to Lord Eliot's financial worries.

While Lord Eliot's reaction to his son's choice of bride did not come as a surprise to those who knew him, it certainly did not sit well with the bride's younger brother. In response to a letter written by Lord Eliot to Pitt (who stood in the place of Harriot's deceased father) requesting a delay, Pitt's strong letter of disapprobation of the suggestion was succinct and to the point. Lord Eliot was free to give them the inheritance later on, but Pitt would settle on Edward James the valuable government position of King's Remembrancer of the Exchequer in lieu of his sister's dowry. This post supplied a salary of £1,500 a year and was the subject of many reports and letters at the time — most of them ready to abuse the young Prime Minister for his obvious preference of a friend and relative. Pitt confided to Wilberforce that, while he did not consider the abuse just, it was, perhaps, plausible, but he had abundant reason to "endure with patience". Happily, he did find one public friend in the voice of the "Hampshire Chronicle", when (on the third of October) the following commendation was published on the front page of the paper:

"The exemplary conduct of Mr. Pitt, in regard to the office of Remembrancer, deserves the warmest eulogium, and yet to the disgrace of those gentlemen who are employed in his suite, not a syllable has been uttered in his praise. Shall his conduct with respect to the Pells be extolled, and his more manly — more liberal — more becoming conduct on this occasion be overlooked? In this instance he has yielded to the dictates of proper affection. He has not, as we said, disposed of the place for the sake of a vote — for Mr. Elliot voted with him before. He has not opened or shut the mouth of a venal orator — for Mr. Elliot is no speaker. He has rewarded no apostasy — for Mr. Elliot has been regularly his friend. But with the love and tenderness of a brother he has given that provision to the valued husband of his sister, which the misery of Lord Elliott refuses to a son. This is virtue, we say again, superior to all the quackery of the Pells."

Personal acquaintances also saw the appointment in a similarly understanding light. Writing to the Duke of Rutland on 23 Sept. 1785, Thomas Orde commented on the situation saying, "The office . . . is given to Lady Harriot Pitt as her portion upon her marriage tomorrow with Mr. Eliot. It is worth £1,500 p.a. net. Old Lord Eliot will, it is hoped, be softened by this accession of income." At the same time, Mrs. Boscawen wrote: "Lady Harriet Pitt if she goes on as she begins will be a fine fortune, and Lord Eliot who I hear has not taken out his purse upon this occasion will soon swear ‘there is no need'."

Apparently, the settlement of the position was satisfactory to Lord Eliot. He was at peace with his son and new daughter-in-law quite soon, since the pair travelled down to Port Eliot within a couple of months of the marriage. Harriot made a good impression on her in-laws, and Lady Eliot was quick to send favourable accounts of her new daughter-in-law to a number of friends. These letters even spread as far as the palace, where the King himself assured Lady Harriot that she was now greatly in her new father-in-law's favour and that the trouble was about "nothing but money."

Whatever family relations had been strained by this marriage, Edward James was soon back in regular communication with his father and paying normal visits to Cornwall. His friends, on the other hand, had rejoiced in his happiness from the beginning — though perhaps not in the most timely manner. Wilberforce happened to be on the Continent at the time of the wedding and was not even sure of the exact date, due to his friend's complete lack of correspondence. So, poor Wilberforce found it necessary to chide his friend:

"As I have not the gift of second sight, nor you the faculty for letter writing, I don't know whether I am addressing a simple Knight Bachelor, or that more respectable character: a married man."