John Eliot Pringle (1842 - 1908)

John was the third child and second son of John Pringle and Georgiana Ramsbottom, known to his family and friends as "Eliot".

Eliot was born in Paris, France (as a British Subject), on 3 Apr 1842 and baptized there six weeks later on 15 May 1842. Eliot's father was a senior officer in the Coldstream Guards (during a relatively peaceful time in British history), which allowed for plenty of time for family travel. As he had a fondness for the Continent, the family spent as many as six months of each year in France, so it was here that Eliot spent much of his childhood. The Pringles lived in many different places, and Eliot and his siblings were as fluent in French as they were English. Claire Clairmont (a friend of Eliot's parents) was always full of praises for the older Pringle children, calling them "lovely and pretty . . . and so full of character — so clever and independent, but so soft and affectionate — not a jot will they yield if they are harshly treated, but will for kindness, or a kind look, do the most impossible tasks".

Eliot's naval career began at an early age, and he attended Mr. Eastman's Preparatory Naval Establishment in Southsea to ready himself. In 1854, he was listed as a Flag Officer in the Royal Navy and – in January of the following year – received a certificate as a Naval Cadet at the Royal Naval College. Unlike his father, Eliot had a career full of military action, seeing his first active service that same year in the Baltic at the bombardment of Sveaborg (in the Gulf of Finland) aboard H.M.S. Hastings.

Eliot then served on the H.M.S. Centurion and H.M.S. Tragalgar before being transferred to the H.M.S. Gorgon. It is here that the first recorded story from Eliot's Naval career was recorded by William Devereux, one of his fellow sailors. On the morning of January 28, 1861, the fearful cry of "A man overboard!" was heard across the deck. A boy named John Parkis had fallen into the sea. As a boat was being lowered, Midshipman Eliot Pringle leapt over the side of the ship and swam as quickly as he could towards the poor boy. For a moment, those men on the ship lost sight of both boys, but Eliot reached Parkis and managed to hold him above water until the rescue boat arrived. It was hoisted up with Eliot lying pale in the bottom and the rescued boy gasping for breath and nearly dead. Parkis was brought around by the ship's doctor, and Eliot was helped to the deck where the Captain came to congratulate him saying, "Well done; you're a noble little fellow, and an ornament to your profession." He was then given a stiff glass of grog and put to bed. Devereux records that the entire ship was full of admiration for the heroic rescuer, and 18-year-old Eliot was awarded the Bronze Medal of the Royal Humane Society.

Several more transfers followed to various ships, not to mention a couple of promotions. Not one to sit back and wait for things to come to him, Eliot was recorded again – just two years later – in the rescue of another poor boy who had been swept overboard. This time, our hero was serving as Lieutenant on the H.M.S. Scylla, a wooden screw corvette under the command of Captain R.W. Courtenay. At two o'clock in the afternoon, on the thirteenth of October 1863, a first-class boy named O'Neil was blown overboard. The patent buoy and ring buoy were thrown to him and, being a good swimmer, he was able to grab hold of both. The newspapers reported that, "under the old system of lowering boats, his recovery would, however, still have been almost impossible from the state of the weather, but a boat slung on Kynaston's patent was promptly lowered with the greatest facility and manned by Lieutenant J.E. Pringle and a boat's crew." O'Neil was rescued and the boat rehoisted without any damage.

Lieutenant Eliot Pringle's first command was announced in January 1875, when he was listed as commanding the gun-boat Tyrian. Active duty obviously agreed with young Pringle, and he served on many ships as he advanced up the promotional ladder. At the age of 35, just three years after gaining his first command, Eliot was listed as Commander of H.M.S. Vulture, a screw gun-boat which he commanded for two years, sailing from the Persian Gulf to the East Indies and back to England. Some of Eliot's adventures during this two-year cruise were related by Sir William Laird Clowes in his 1907 history of the Royal Navy:

In the Persian Gulf, in 1878, Pringle's boats were engaged in an action of some importance. The 'Vulture' proceeded to Bahrein in October of that year in order to exact certain fines from the head men of the island for the infraction of a treaty which had been concluded in 1861. On arriving, she learnt that all communication with El Kateef, on the mainland, was suspended, and that that town was beleaguered by about 3,000 Bedouins. Pringle, in consequence, went on to El Kateef, and communicated with the governor, who informed him of the presence of a considerable piratical fleet of dhows near Ras Tinnorah. The 'Vulture' steamed thither, and on October 10th found the dhows close in shore in shoal water. Although it was blowing half a gale, Pringle manned and armed his boats, and led them to the attack. Six of the largest dhows made sail and stood out to engage, while the others, and many people on shore, opened a brisk fire. The British, however, pushed in, drove the Arabs from their vessels, and harassed their retreat with shrapnel and rockets. It was ascertained that the enemy lost no fewer than 34 killed and 85 wounded, while the attacking party escaped scot free. Twenty dhows were taken possession of, and, each in charge of a bluejacket, were navigated to El Kateef. The capture of the flotilla relieved the governor, who had long suffered from the depredations of the marauders and of their allies on shore.

After this brave encounter, Eliot continued with the Vulture, making a tour of Bushire, Bahrein, Bombay and Muscat before arriving in Devonport to be paid off. While sailing near Bahrein in May of 1879, Eliot sighted an "unusual phenomenon" at sea. He wrote a detailed and sensible report of this interesting occurrence to the admiralty. Looking at this report today, it seems like something out of a Jules Verne novel, but Eliot was able to keep his imagination in check and report only the facts!

In February 1882, Eliot was appointed Commander of the H.M.S. Falcon, a gun vessel belonging to the Mediterranean Squadron, which saw plenty of action right away. During the Egyptian War that year, Eliot received the Egyptian medal, the Khedive's bronze star, and the Medjidiah of the third class (which award was upgraded to second class in 1888). In 1883, Eliot successfully landed a detachment of seamen and Marines at Port Said, quelling a disturbance there. For this action, he received a letter of thanks from the principal inhabitants.

In April of 1884, the Commander cruised the Falcon along the coast of Italy, going on to Gibraltar to await further orders. Eliot arrived there on 20 Jun 1884, only to receive the news – three days after his arrival – that his mother had died on the island of Malta. Obviously, the news reached him quickly, because the Falcon left for Malta on Sunday, 29 Jun 1884. Presumably, Eliot settled his mother's business there and saw to her burial — where a very large and beautiful stone monument was placed over her grave. It's very likely that Eliot's youngest sister, Blanche, was at Malta with their Mother. If this was the case, then he was the one who arranged her passage to Constantinople and finally home to England. By November, Eliot was back on the Falcon, sailing for Suakin and Massowah, between which ports he remained until February or March of the following year, when he left the Falcon and sailed for home. Captain Eliot arrived in England by March of 1885, and his foreign naval service was over.

Once back in England, Eliot set up residence at 76 Marine-parade, Brighton and leased Digswell House (in Welwyn, Hertfordshire), just houses down from his sister, Eleanor Plaoutine, and her family. As one of his mother's executors, he proved the will in London in March 1885. It seems likely that his sister, Blanche, was living with him in Brighton until her marriage, later that summer, to a fellow officer of the Navy, Lt.-Commander Henry Jauncey. (Jauncey had recently been serving aboard the H.M.S. Cygnet at Port Said, so it's likely that Eliot had there met his future brother-in-law.) Wedding bells tolled yet again that year in the Pringle family, and Eliot Ayot St. Lawrence in Hertfordshire on the 16th of September for the wedding of his youngest brother, Reginald. (Eliot can be seen standing at far right in the wedding photo below.)

Captain Eliot's active Naval career was drawing to a close, and he (at this time on Half Pay) spent some time in Hertfordshire. In fact, he spent enough time there to cultivate a relationship with Inez Crawley, the older widowed sister of his new sister-in-law. At the age of forty-four, Eliot married Inez on 23 Oct 1886, at the same church where he attended his brother's wedding just one year earlier.

On 20 Jun 1887, Eliot Pringle was removed from Half Pay and appointed Captain of H.M.S. Cyclops, the lead ship of the Cyclops-class breastwork monitors. This was a short appointment, since he commanded the Cyclops for less than two months. She participated in the annual fleet maneuvers and served in the Fleet Reserve — and Eliot Pringle was appointed just for the 1887 Naval Review at Portsmouth.

In 1890, Eliot was listed as Captain of H.M.S. Carysfort, a Comus class screw corvette, but any active service aboard this ship was short-lived, since she was ordered to return home to Pay Off the following month. This was Eliot's last naval activity, since he went on Half Pay for the final time in 1891, placing himself on the retired list in April 1892 (receiving retirement pay of £470 a year). In 1899, the Navy advanced him to his final promotion with the rank of Rear Admiral. (He was one of nine captains from the retired list to receive this flag rank on the same day.)

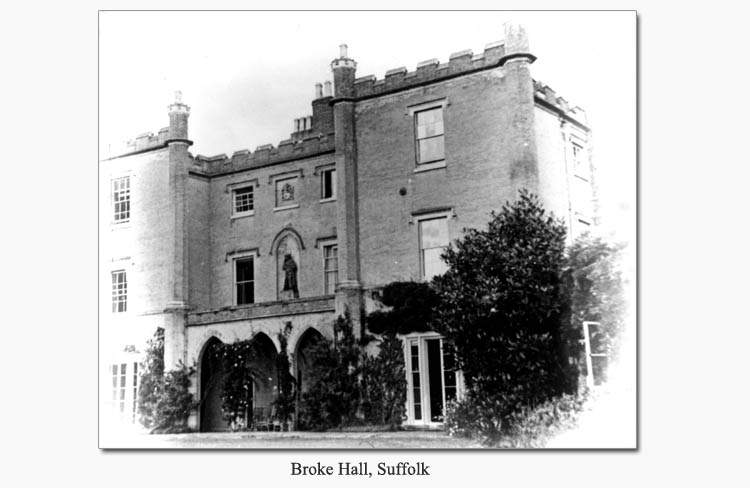

The couple never had any children of their own, but the new Mrs. Pringle had eight surviving children from her first marriage, and Eliot treated them as his own. The new family lived at The Mansions in Ayot St. Lawrence, where Eliot served as County Magistrate. By the time of the 1901 census, Eliot and Inez had taken a city house at 65 Cadogan-gardens in London, Chelsea, and only the youngest daughter, Georgina, was still at home. 1901 was a busy year for moving, because Eliot also leased the country home of Broke Hall in Ipswich, Suffolk. To make matters even more confusing, Inez had kept her villa, La Loggia, on Via dei Colli in Bordighera, Italy, and the family's time seems to have been divided between the three houses. Eliot kept a small private yacht at Ipswich (with "a delightful old seaman to look after it") and enjoyed riding horses. He helped his youngest sister, Blanche (now widowed with two small children), to find a house near his own country home at Broke Hall in Ipswich, so he saw a lot of his niece and nephew, Eleanor and Jack Jauncey.

Eliot and Inez enjoyed the freedom of his retirement, and they spent a good deal of time in Italy. It was on one of their trips to the villa at Bordighera, in March of 1908, that Eliot passed away of heart failure — missing his sixty-sixth birthday by one month. Although no burial record or funeral information has been forthcoming, it is very likely that he was buried at the English Cemetery in Bordighera.

Rear Admiral Pringle's £27,000+ estate contained many of the Chatham family heirlooms which had come to Eliot on his father's death. To the upset of the Pringle family, these items were divided between his stepchildren, the Crawleys, with the vast collection of Chatham Papers bequeathed to the Public Record Office for the "use of the nation and for purposes of historical research". His portrait of William Pitt the Younger (painted by George Romney, but mistakenly attributed to Joshua Reynolds) was bequeathed to the National Gallery "for the use of the nation" with instructions that it not hang in the National Portrait Gallery. It still remains at what is now known as The Tate (originally known as the National Gallery of British Art) but is, unfortunately, not on display.

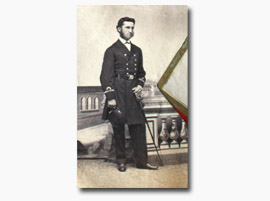

Portraits

One painted portrait of John Eliot Pringle is known to exist today. It is a large watercolour portrait painted at the time of his appointment as Flag Officer in the Royal Navy in 1854. Numerous photographs also survive.