John Henry Pringle (1809 - 1868)

John was the third child and only son of William Henry Pringle and Harriet Hester Eliot.

John was born in London on 7 Oct 1809 and baptised at St. James, Westminster, on the first day of November — exactly twenty-three years to the day after his mother's own Christening. John's childhood and school years are shrouded in a bit of a historical mist, due to a lack of surviving family letters. He spent his first few years at home with his mother, while his father was on the Continent engaged in the Peninsular War. He must have attended some sort of school later, as the first recorded event in his life is the fact that he was given the rank of Ensign in the Coldstream Guards on Christmas Eve of 1825. John was sixteen years old and an official member of his father's old regiment. (Within ten years John held the rank of Captain, eventually retiring with the rank of Colonel.)

John was the great-grandson of William Pitt the Elder, a family connection that he was very proud to claim, and retained close ties with his Uncle John (2nd Earl of Chatham). So close, in fact, that – on Chatham's death in 1835 – John was co-heir to his estate (with his cousin, William Stanhope Taylor). The cousins did much for the preservation of the Pitt name in history, editing and publishing the papers of their great-grandfather in 1840. The family honor was a dear thing to John, and he was quick to defend it. In 1835, upon discovering the phrase (referring to the recently departed Lord Chatham) "whose military incapacity has caused the glorious title of Chatham to be scorned" in Sir William Napier's printed "History of the Peninsular War", heated correspondence followed, resulting in a "piecrust" promise to strike the libel in future editions. This episode is a fine illustration of John's inherited Irish passion.

For a career officer, John had a very poetic soul. He wrote a volume of poems called "Algiers the Warlike" (published in 1846), as well as lyrics for several songs. A notice appeared in English newspapers in early December 1839, advertising some new songs by Captain J.H. Pringle. John wrote "the poetry", and the music was written by "a Lady". The songs were priced at 2s a piece and published by Lewis Lavenu, music seller to the Queen. The titles of the pieces were "The Breezes Revel with the Rose" (a song), "Her Dark Eyes Beam of Glory" (a song) and "Where is the Summer Now?" (a Fairy Dirge for three voices). How sad that no copy of these songs appears to have survived.

While he may have given ample demonstration of his poetry in his personal time, John was just as capable of proving himself a good officer, even at a young age. His military career took place during a rather peaceful time for the Coldstream Guards, and there is no evidence to show that he ever saw any kind of war-like action. He was a capable commander of men, however, and it was proven in October 1835 – when the public was first introduced to this descendant of two eminent Generals – on the occasion of the Millbank Penitentiary Fire. A great disaster which (after hours of firefighting) ended with the utter destruction of the laundry and the entire female side of the prison. A detachment of Coldstream Guards arrived on the scene two hours after the fire started, in order that they might assist the police and the fire engines. These men were led by Captain Pringle (mistakenly identified in some news reports as an officer of the Scots Fusilier Guards), whose gallant behaviour and firm leadership of his men attracted a good deal of public attention, including the following report:

Captain Pringle, in his statement (published in our last week's paper) alluded to a person that "was employed in beating down the burning wall, others holding him lest he should fall into the fire." This nameless person was Captain Pringle himself, whose cool and intrepid courage upon this occasion is said to have been most admirable and praiseworthy. On the cracking and sinking of the ceiling, the party under his command rushed towards the door pell-mell; but the Captain kept his post steadily, ordering them to fall into single file, an order which was obeyed with as much precision as though they were on the parade ground.

In the same year of 1835 (which proved to be a very busy one for him), John married Miss Georgiana Ramsbottom, the third daughter of James Ramsbottom of Clewer Lodge in Windsor, Berkshire. The particulars of this marriage can be slightly confusing, though, without a bit of research. At first glance, you find a record of their marriage on 24 Dec 1835 at St. Anne's Limehouse in London. Their first child, a son, was born (not five months later) in Orleans, France (on 9 May 1836).. Four years later, John's father died (in December 1840) and – in less than a month – newspapers and magazines across the United Kingdom published the following announcement:

On the 24th of March, 1835,

Capt. J.H. Pringle, of the Coldstream Guards,

to Georgiana, third daughter of

J. Ramsbottom, Esq. of Clewer Lodge.

Why publish a marriage announcement four years after the event? And why publish it in so many papers? After spending quite a lot of time researching this, it appears that John Pringle and Georgiana Ramsbottom married in France on the 24th of March. A marriage in France was perfectly legal, but it was not considered legal enough when proving legitimacy as the heir of an estate. It seems to have been common advice to couples during this era to come home to England and marry again in Britain. Often, this step was suggested once the first child of the marriage had been (or would shortly be) born. In John and Georgiana's case, they were less than five months away from the birth of their son when they "married" in London, and no newspaper announcement seems even to have been published for this later British ceremony. The fact that their marriage in March was announced just weeks after John's father died would point to the idea that they were making sure that their son was recognized as the fully legal heir. So far, I have not been able to locate a French marriage record, but without knowing which town they were married in, I have no way to search for one. I have no doubt that something will turn up in the future.

John and Georgiana Pringle had a happy family life, and they were blessed with four sons and three daughters. They moved to several different homes in Brighton and London but appear to have stayed the longest at 4 Bentinck-street, Cavendish Square. Until her death in 1863, John's mother-in-law lived with them – along with her youngest (and unmarried) daughter, Ada. John was able to spend up to six months of each year on the Continent (usually in France, particularly near Paris), and all of John's children were as fluent in French as they were English. On occasion, the family stayed on in France while John returned for duty with his regiment in England. A glimpse into the Pringle family's life can be gained through references in many surviving letters from Claire Clairmont and Mary Shelley. John and Georgiana were, for many years, close friends of Miss Clairmont. She was full of praises for both them and their "lovely children", stating that their house was a place of order, where the "decencies of life" were preserved and each person did his duty and helped the others. John often assisted her financially, when she found herself in straitened circumstances, even purchasing her opera box for the unheard-of (but most helpful) sum of £290.

By 1853, John had placed himself on Half Pay — which amounted to the sum of eleven shillings per day. By March of this same year, he was also given the civil situation of "Gentleman at Large" in the Viceregal Court of Ireland, under his cousin, Edward Granville Eliot (then 3rd Earl of St. Germans and Lord Lieutenant of Ireland). This position came with a stipend of 128 pounds, 18 shillings and 8 pence a year. While his name appears on several court lists, the definition of this position has faded with time, and just how often John would have been required in Ireland is uncertain. He did attend the Garrison Amateur Theatricals at the Queen's Theatre in Dublin in February 1853 as one of a large Viceregal party, but other reference to his presence has not surfaced.

In June of 1854, while still on Half Pay, John was promoted to the Brevet rank of Colonel, making him an officer of staff rank, no longer attached to a particular regiment. Interestingly enough, he was never called to serve in the Crimea. Instead, he and his good friend (also of the Coldstream Guards), Colonel Edward Bootle Wilbraham, were appointed commanders of the 6th Royal Lancashire Militia, with John serving as Lieutenant-Colonel Commanding. He proved a good commander and was well-liked and obeyed by his men. While the regiment was stationed at Manchester in 1857, the officers (led by Lt.-Col. Pringle) attended an evening performance of "Lancaster's Panorama of the Late War" on exhibit at the Exchange Rooms. (This entertainment was well-known throughout the country, having begun in 1855 and continuing on to include scenes of the Indian Mutiny. Large panoramic paintings were displayed, depicting scenes from the Crimea – featuring the major battles of the Alma and Inkerman, the Siege and Fall of Sebastopol, the Light Cavalry Charge at Balaklava, the Fall of Sweaborg and the Storm in the Black Sea. As these paintings were displayed by gas light, a gentleman narrated the scenes, singing popular songs between intervals. In honor of the officers' attendance, a private band performed selections of appropriate music.)

After six years of service, John retired from the Militia regiment, and his officers presented him with "a handsome salver and tea and coffee service". At the age of fifty-one, John had finished his military career, but family considerations more than occupied his time. That same summer, his oldest daughter married an officer of the 18th Hussars, presenting the family with a grandson the following year. The Pringles now had as much time as they could wish to travel, and it seems that they spent a good deal of time in London, Brighton, France and even Switzerland. They attended a large amount of balls and assemblies in high society, and John's name was published as patron of the "South Kensington Hotel Company" and the "Practical Military Institution", a school for young gentlemen destined for the military profession.

John certainly handled all of the family business after his father's death. He purchased plots at Greenwich Cemetery and Kensal Green Cemetery, handling the burials of his parents, his mother-in-law, his sister and his brother-in law. Sadly, he even had to bury his oldest son, Henry. (The two were staying at the Great Northern Railway Hotel in December 1858 when Henry died from "a fit". John was called to give evidence at the inquest, and then went home for a very sad Christmas.)

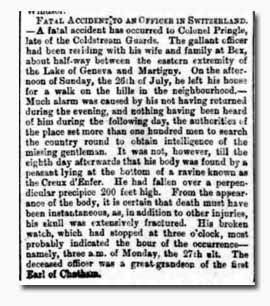

By 1867, John and his family were again in France. This time, their travels took them to Nice, where twenty-five-year-old Eleanor married the Russian Colonel and A.D.C. to the Tsar, Serge Plaoutine. The two families must have lived near each other, because John was at Nice to sign the birth registration of his third grandson, Nicholas Plaoutine. (It is around this time that the only known photograph of John Henry Pringle was taken.) Later that same year, John and Georgiana took their younger children and spent time in Bex, Switzerland, the last trip he would ever take. On Sunday evening, July 26, 1868, John left his house for a walk in the neighboring hills, while his family waited for him to return to dinner — but he never came home. The alarm was called after nothing could be heard of him, and – on the following day – the authorities set more than one hundred men to search the countryside. Eight days later, a peasant found John's body at the bottom of a ravine known as "Creux d'Enfer". Judging from his broken watch and the extent of the injuries, John must have gotten lost in the hills in the dark, and (at three o'clock in the morning on July 27) he fell 200 feet over a perpendicular precipice.

John was buried at the cemetery in Bex on 3 Aug 1868. An impressive tomb was erected over his grave by his oldest surviving son, John Eliot Pringle. His youngest daughter, Blanche, kept black and white photos of the tomb, along with a photo of the precipice (marked with an "x" on the spot where her father fell), in a black bordered envelope with "Photographs of Dear Pappie's Tomb" written on the front.