William Henry Wilbraham Pringle (1836 - 1858)

WHW Pringle was the first child and first son of John Pringle and Georgiana Ramsbottom, known to family and friends as "Henry".

Henry was born in the French province of Loiret on the ninth day of May in 1836, when he entered the world at nine o'clock in the evening at his parents' home at 9 Rue St. Marceau, Orleans. The following morning, at the local Town Hall, an official French birth certificate was filed under the impressive name of William Henry Wilbraham Pringle. (Why his birth was registered in this civil manner, instead of the expected Ecclesiastical Return, is a mystery, as Henry's parents were always British subjects who spent quite a lot of time in France. In fact, two of his younger brothers were later born in Paris, and they had the customary Ecclesiastical Returns filed for their CofE baptisms.)

Henry was the first grandchild on his father's side of the family, so there must have been great rejoicing at the time of his birth at the prospect of another name to add to a long list of decorated military officers. Shortly after his birth, on the seventeenth of July, he was baptised in the rites of the Anglican Church by the pastor of the Christian Protestant Church in Orleans, France. Henry's godparents were Emily Ramsbottom (his maternal aunt) and Captain Edward Bootle Wilbraham of the Coldstream Guards (good friend of his father) – a couple who would actually marry five years later!

By all accounts, Henry was a "beautiful" child and very well behaved. His childhood was spent at home – whether in England or France – where he and his younger siblings were privately tutored. At the age of fifteen years, in the best Pringle fashion, Henry was admitted to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich. Sadly, he was unable to meet the academic requirements in the later examinations and, after two years, was removed "by order of the Master General". This step was typically taken to avoid embarrassing the school or the student who had no hope of passing.

How disappointed Henry (and family) must have been can only be imagined. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather were all high-ranking career officers (the two latter gentlemen well-decorated Generals), so Henry had generations of distinguished ancestors to follow. While two of his brothers would do well in the military – one as a Rear-Admiral in the Royal Navy and the other passing the Woolwich Examinations and ending as a Major in the Royal Artillery – Henry just didn't have the academic skills necessary to lead him into and through the brilliant military career that he so desired.

Two courses were open to young Henry at this point in his life. He could choose to enter the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, where academic requirements were not particularly demanding and officers were expected to purchase their commissions, or he could enter the military service of the East India Company. For unknown reasons, Henry opted out of purchasing a commission in the British Army and chose the East India Company. The downside was that this was a much more dangerous option, since life in India was known to be difficult, and young officers often did not return. The upside was, however, that service in the EIC was an honourable choice, one that would allow Henry to prove himself in action (since he could not prove himself in academics). Once the choice had been made, Henry's father turned to family for help, and we find that Lord St. Germans "recommended" his cousin's son for appointment to the Bengal Infantry. Henry was examined and qualified at Addiscombe House, the academy of the East India Company, and on 5 Aug 1854 was given the rank of Ensign in the 22nd Bengal Native Infantry (BNI).

Instead of finding distinction or promotion, though, Henry passed a rather tranquil eighteen months in India. (In fact, the only action recorded for him was a short posting to the 58th N.I. at Jhelum.) In June of 1856, it was reported in the military lists that Lieutenant Pringle of the 22 B.N.I. had returned to England – sent home "invalided from the effects of the sun" – having been granted a medical certificate allowing him to remain in the country for four months. It is known that, during his short stay in India, Henry's health was compromised, causing him to be subject to occasional fits, but the full extent of his illness would not be revealed for two years to come.

After the producing of several additional medical certificates, Henry found himself forced to relinquish his hopes for an army career and enrolled at Clare Hall, Cambridge, in 1858. This body would later become Clare College, but its claim at this time to any academic standing was low. Clare boasted only about 70 undergraduates, with Choir and Cricket known to be the "main" subjects. Henry was admitted to Clare as a pensioner, which meant that he paid his own tuition, room and board, instead of receiving any form of scholarship. Obviously, Henry's academic prowess had not improved since his Royal Military Academy days.

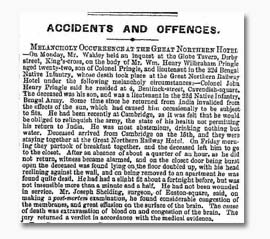

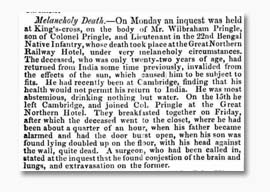

On Wednesday, 15 Dec 1858, Henry travelled up to London from Cambridge to meet his father for the Christmas holiday. They stayed for a couple of days at the Great Northern Hotel, a rather new building across from the King's Cross station. They had breakfast together on Friday morning, after which Henry excused himself and went to "the closet". After an absence of about fifteen minutes, Henry's father became alarmed and called for the door to be opened by force. Poor Henry was found on the floor, doubled up with his head reclining on the wall. A doctor in the hotel was called immediately, as it was thought that Henry was just suffering from a fit. On carrying him to one of the apartments, however, it was discovered that he was dead. An inquest was held three days later at the Globe Tavern in Derby-street, King's Cross, and Henry's father was one of two witnesses. John Henry Pringle testified that his son was "most abstemious, drinking nothing but water", and also that he had been subject to these fits (though not too often) since his return from India. He had suffered a slight fit about two weeks before, but he had been insensible for no more than a minute and a half.

It was a very sad Christmas for the Pringles that year, because their much-loved Henry was buried (above his grandparents, General and Lady Pringle) – just two days before Christmas – in the catacombs beneath the Anglican Chapel at Kensal Green Cemetery in London.

Postlogue

Although the name was not applied to the ailment at the time, the published results of the post mortem (along with Henry's noted symptoms) sound very much like Cerebral Malaria to modern researchers. This was a common problem for soldiers in India, and it would be some decades before the condition was given a medical name. If a silver lining were to be searched for in this heart-wrenching story, however, one can be found in the timeliness and location of Henry's death. As heart-breaking as the circumstances were, the fact that Henry was invalided home in 1856 from India saved him from certain death on the eighth of June 1857, when his regiment mutinied at Fyzabad and his fellow officers were massacred. Henry's family were able to spend another year with him at home and did not have to bear the news of his horrible death in what is commonly referred to as "The Indian Mutiny". One can only hope that there was a bit of comfort in this knowledge.

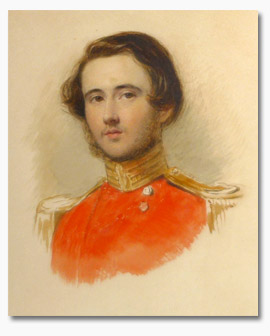

Portraits

Two known portraits of William Henry Wilbraham Pringle exist today. One is an oil miniature showing him as a small baby in the arms of his mother. The second is a larger watercolour portrait painted at the time of his appointment to the Bengal Native Infantry in 1854.