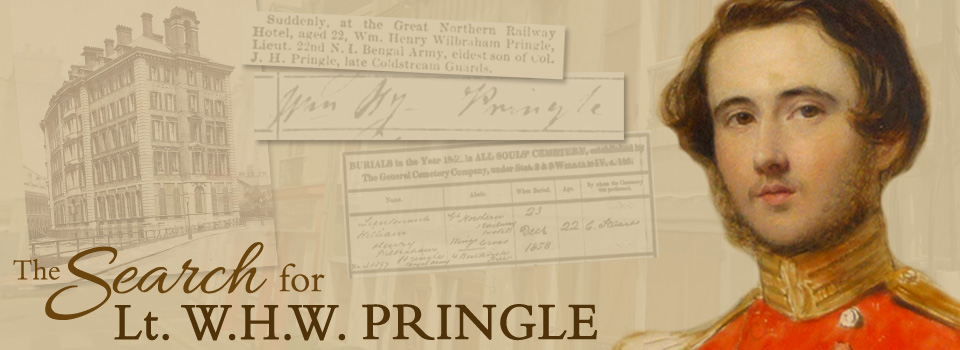

The Search for Lieut. W.H.W. Pringle

When it comes to genealogical and historical research, the tracing of the descendant line of General William Henry Pringle and Harriet Hester Eliot has not been a very simple nut to crack. My original research began with Harriet Hester's father, the Honorable Edward James Eliot (friend and confidant of William Pitt and William Wilberforce, as well as early member of the well-known Clapham Sect), in the last months of 2011. As Eliot's daughter and only child, Harriet Hester and her family were meant to have been the "end of the line" – a small part of the overall project. In fact, I originally figured on doing just enough basic research to place memorials for Harriet Hester and her family onto FindaGrave.com. One thing led to another, however, and I'm knee-deep in the history of the entire Eliot family of Port Eliot (including their line of Pringles).

During any research, it can be very difficult to narrow things down correctly or to keep yourself from ascribing what turn out to be imaginary motives to your people. (I have a very good imagination, too, and that's a bit of a handicap sometimes.) The finding of some of the Eliot individuals has been fairly straightforward, while others took a little longer to uncover. The prize-winning person for Most Challenging Research Project, though, without a doubt, has been Lieutenant William Henry Wilbraham Pringle. Much time and hard work goes into turning each and every person into a living persona and not just a name on an index page, but no one has needed more than W.H.W. Pringle!

Six months after the beginning of my research on Edward James Eliot, I discovered the existence of his great-grandson, William Henry Pringle, on the 1851 England census. Before I felt able to say that I had a fairly good idea of "little William Henry" as a person, a long eighteen months would pass, and I now feel as though I've actually met the Lieutenant. While solving the mystery of WHW Pringle, though, almost everything that could have gone wrong (as far as mis-assumptions and imagination goes) went wrong. Perhaps the retelling of my journey will give some guidance to others who wish to research their own officer in the Bengal Army. Or it might give others an idea of just how much work it's taken to put all of this information together. Or it might just supply a little entertainment to those of you who've already been through a similar situation. Regardless of your reason for being here, let's begin at the beginning . . .

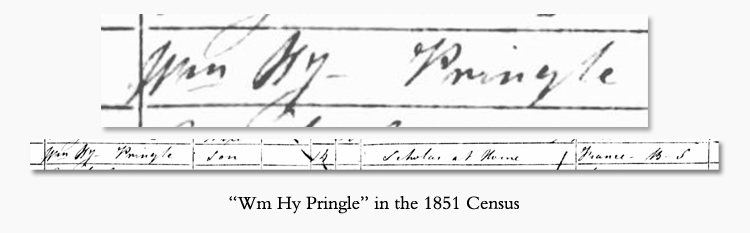

Henry was the oldest child of John Henry Pringle and Georgiana Ramsbottom, making him the first grandchild of William Henry and Harriet Hester (Eliot) Pringle. As a boy, Henry was remembered by Mary Shelley as being a "beautiful" child and very properly behaved (gleaned from hours of reading through the published letters of Claire Claremont). The first reference to him that I was able to find – and the only reference I had for about a year – was Henry's name written on the 1851 census (a good starting place for your research). He was recorded as "Wm Hy Pringle" (abbreviations not converted to William and Henry by most search engines, so keep searching with variants), a fourteen-year-old scholar at home with his parents at 13 Kensington Gardens in London. His birthplace was marked as "France – BS", which means he was born in France as a British Subject and should have been on the index of Ecclesiastical Returns. I had already learned the names of Henry's six siblings, but the discovery of this oldest child was unexpected – even though I had often wondered why there was no child called after General W.H. Pringle (his much-decorated paternal grandfather).

As aforementioned, I spent a year with no other information about Henry. My trip to the census returns had been a stab at finding Henry's sister, Violet (I had known about her for some time and simply liked her three given names). It was a lesson hard-learned, because I should have consulted the census returns in the first place. There he was – a wrench in my well-oiled machine!

I gathered small clues about this "surprise" child during the next year, but no hard facts were forthcoming. It was obvious that he had died before his father, since I already knew that Henry's younger brother had inherited the majority of the family property. That seemed like a good starting point, since it narrowed the search field down to the years between 1851 and 1868 and led me to searching through records for any William Henry Pringle dying during those years. It's not an uncommon name (which makes the search a little more difficult), but there was a result for a man by that name who died in Newington, London, in 1856. That was a pretty good fit, so I put that in my family tree as a possibility and looked for more clues. I even spent some time trying to find an address for the Pringles in Newington. Nothing – no results.

I combed through the "Ecclesiastical Returns for British Subjects Born Overseas" for the ten years following his birth, which should have yielded a result without much effort. Two of Henry's brothers were there, and their records came up right away. No matter how hard I looked, though, there just wasn't anything for Henry. Discouragement and boredom (plus the fact that I was really tired of browsing dead ends) led me to drop this line of inquiry for a while and move on to another part of the family.

I'd like to stop here for a brief message and share a hard-learned lesson with you. The women of the family count for more than you think. Do not neglect to research your person's mother and her parents/siblings! Until this point in my research, I had devoted little more than a cursory glance (as most/many genealogical researchers are inclined to do) at any of the wives and mothers. BIG mistake! Maiden names and given (as well as married) names of Aunts and Uncles can be the key to unlocking your mystery. Family names were often passed down generation after generation, and research which neglects this fact will always disappoint.

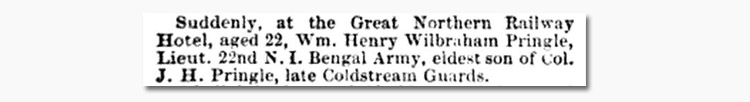

So . . . having left little Wm Hy Pringle behind, I returned to researching other names in the family and inadvertently hit upon the sister of Henry's mother, Emily Ramsbottom. She had married Lieut.-Col. Edward Bootle Wilbraham of the Coldstream Guards – who also happened to be the close friend and fellow officer of her brother-in-law, John Henry Pringle (Henry's father). Do you see where this is going? While typing in a search for Wilbraham of the Coldstream Guards, a little search result on Google books showed up with a short death notice from "The Gentleman's Magazine" of January 1859. It read:

I couldn't believe it! There it was, staring at me in black and white. I still remember the look of those words on my screen, and the feeling of disgust that overcame me with the thought that it had been sitting there all the time but I had placed too little importance on the mother of my subject. (While there will always be futile searches in your project, I had spent more than had really been necessary on that Newington gent!) After a year of spinning my wheels, so to say, the pitch of excitement and motivation rose again and serious research began once more.

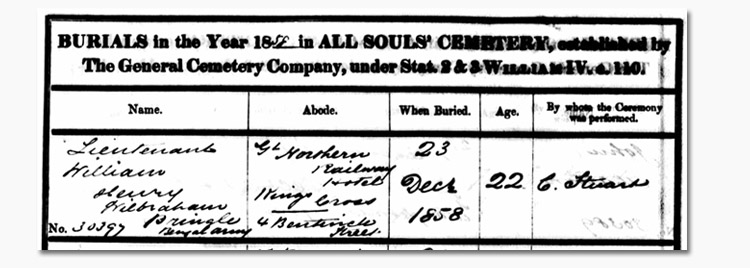

Knowing that Henry had died in December 1858 (Gentleman's Magazine is nearly always one month behind in their reporting) and in London, it was non-stop from here on out. Search engines on genealogical sites (and sites in general) are notoriously poor, and without actually knowing about that second middle name of Wilbraham, nothing had ever come up. (I know, it should have, but it doesn't always work the way it should.) It was simple to find his death record in the Free BMD results, and – considering where he had died – I was pretty sure that he would have been buried at Kensal Green Cemetery (his grandparents and a number of other relatives were buried there). Some of the Bishop's Transcripts of the Kensal Green records are available online, so I typed his name in there and waited for a result. Nothing. That seemed odd, but I tried looking at a few other cemeteries in the area. Still nothing.

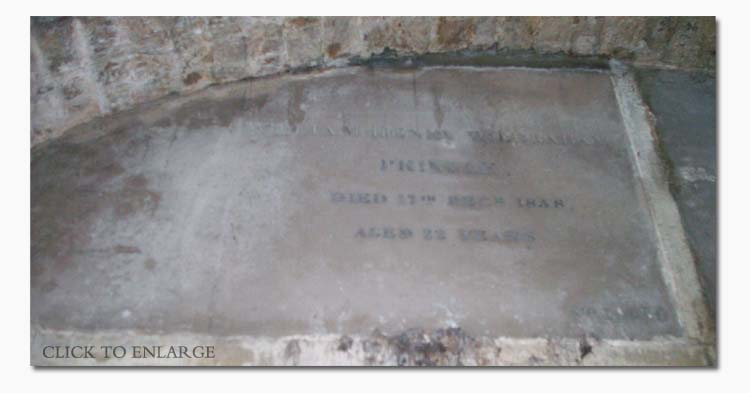

The Kensal Green idea kept nagging at me, though, so I decided to just browse through the images relating to that time period and hope for a result. Sure enough, there it was! He had been buried at Kensal Green, just two days before Christmas. The reason that his record would not show up in search results was due to the fact that his name was listed on the burial records as "Lieut. William Henry Wilbraham Pringle, Bengal Army", and this had been poorly transcribed online to show a last name of "Beryar Arny". The lesson learned here? Don't neglect to BROWSE!

Even though the Kensal Green staff had an awful reputation in earlier days for being mercenary and unhelpful, I learned that a new group (the Friends of Kensal Green) had taken over, so I decided that it was worth a shot. Thankfully, I received a very fast reply to my e-mail, from a wonderfully helpful person who not only gave me the burial-plot information but went down to photograph the grave for me and sent a copy of the original burial record. Sure enough, Henry had been buried in the catacombs below the Anglican Chapel, just above his grandparents, William Henry and Harriet Hester Pringle!

I'm glad that I persisted with this Kensal Green line of pursuit. By all rights, I should have given up any idea of his being there, because (believe it or not) – just months before this – someone had gone down into the catacombs to photograph Henry's grandparents' stones for me. Due to the darkness down in the catacombs, though, they had not noticed that the grave above them also belonged to a Pringle. So near and yet so far! Persistence paid off, though, and I have only kind things to say about working with the great folks at Kensal Green! Take note, though, that memorials in cemeteries and official burial records are not always complete (if they ever were). Many graves were never marked, stones have been removed over the years, and time and vandalism have often destroyed them. Burial records have often been lost or decayed beyond repair, and WWII bombings destroyed many records (not to mention entire burial grounds). Regardless, a search through burial records should always be exhausted before moving on to other areas.

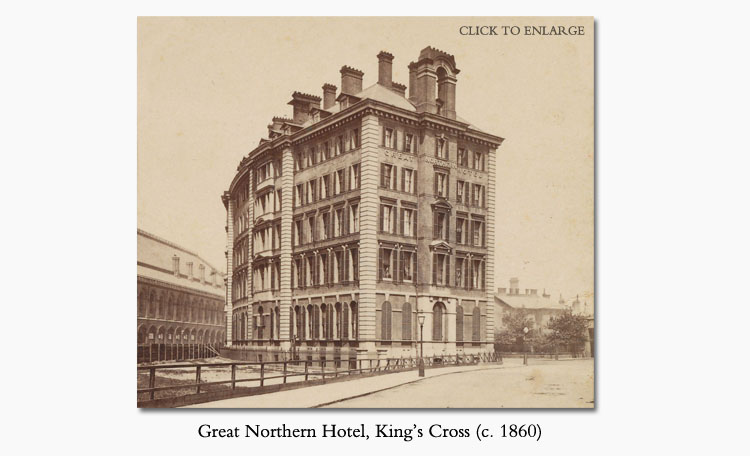

Now armed with the knowledge of Henry's complete name, date of death and place of burial, searching through newspaper archives became much easier. (It's a fact of online research and search engines that you have to know exactly what you're looking for before you can find it. Well, nearly always a fact. And it's getting worse with each passing year.) I was able to come up with a number of obituaries, as well as a fabulously detailed report about the inquest, held three days after Henry's death, at the Globe Tavern in King's Cross. It supplied the information that Henry had actually been invalided home from India in 1857, as he was subject to occasional fits due to "effects of the sun"; had been unable to recover his health; and, after a year of recuperation attempts, had been finally forced to face the fact that he needed to relinquish his career in the Army and look elsewhere for a career.

The inquest report told how Henry had gone on to enroll in Clare Hall at Cambridge, just months before his sudden death, and had just returned home to London for the Christmas holiday. It also gave a detailed description of his last morning, on which Henry was staying with his father at the Great Northern Hotel. Henry excused himself from the breakfast table and went to "the closet". Fifteen minutes later, when he didn't return to the table, his father became alarmed and had the door forced open, only to discover poor Henry slumped on the floor, dead from one of his fits. At the inquest, his father testified that Henry was "most abstemious, drinking nothing but water", and the results of the post mortem showed congestion of the brain. While there was no name for it at the time, the detailed medical results sound very like what we now call cerebral malaria – a common problem for British men serving in India. This was the most detailed inquest report that I've ever come across, and it was thrilling to have Henry's personal story documented like this.

Now that I had this much information and the facts were falling into place, I just had to keep going. This seemed a little harder than normal, though, because I had absolutely no idea what the "22nd N.I." or the "Bengal Army" was or how to find the appropriate records. Some more searching and reading, and I ended up even more confused, so I decided to look for help. Having stumbled across a site called the "Victorian Wars Forum", I decided to ask for advice. This turned out (and continues) to be a blessing in more ways than one. Without some of the very knowledgeable and helpful gentleman over there . . . well, Henry Pringle would probably still be just a uniformed face in a portrait with a sad ending.

A forum member suggested that I contact the British Library in London, as they hold all of the India Office records. This collection has now been digitised and made available online, but back at this time the papers could only be read, in person, at the library. With them in London, and me in the USA, this presented a bit of a problem. After sending an e-mail to the department in charge of the India papers, I received an almost immediate reply from a very wonderful librarian who was not only amazingly helpful but had already photocopied Henry's HEIC cadet application papers and just needed my address in order to get them in the mail to me. Wow! (This was, in fact, the beginning of a lot of dealings with the British Library, and I have always found them quite helpful.)

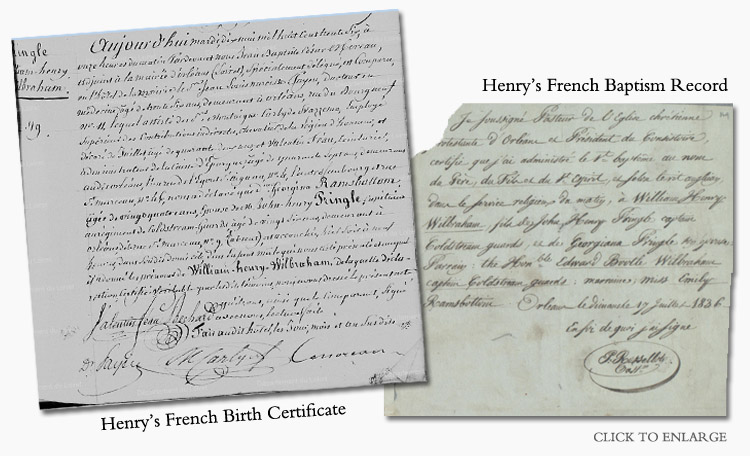

About one week later, the papers arrived and proved to be a goldmine of information. All East India Company (HEIC) cadets were required to fill out an application form, explain the type of education they had received, and supply letters of recommendation regarding their character. Henry had been privately tutored in a classical and mathematical education, but the only public school or university he had ever attended was the Royal Military Academy. He was also required to supply evidence of his age. Usually the young man supplied either a copy of his birth record or his baptism record. Happily for me, Henry supplied both! There was a short version of his French birth certificate and a copy of his French baptism record, which included my long-desired piece of information: his birthday. Armed with all of these new facts, I was able to spend some time on the Loiret, France, provincial archives website, where all the birth records have been digitised and are available to browse. Since I speak/read no French ("merci beaucoup" and "Mademoiselle from Armentieres" did not appear anywhere on the pages), browsing through the French records was tedious and took quite a while. There it was, though – finally – in the Orleans Civil Records of 1836 – William Henry Wilbraham Pringle's full birth certificate!

There was only one small hitch here, though. The certificate was written in French. Thankfully, a very kind lady on an online Message Board was willing to translate both the birth and baptism records for me (don't neglect to ask others for help). There was great information included there, as it supplied the address of the house where Henry was born, the time of his birth, and the names of his godparents (or "sponsors"). Interestingly enough, the godparents were none other than Lt.-Col. Edward Bootle Wilbraham (a friend of Henry's father) and Emily Ramsbottom (Henry's maternal aunt). (This couple would marry five years after this baptism.)

During the very same week that the application papers arrived, I was actually able to find and contact the widow of a direct descendant of Henry's father (search, search, search for descendants – this one came up as the owner of a rental cottage). Just two days after we began to correspond, she e-mailed photos of a beautiful pair of framed watercolor portraits which hung next to the chair where she sat every evening. One was identified by the family as being Henry's younger brother, John Eliot Pringle (later a Rear-Admiral in the Royal Navy), as a boy, the other as his brother, William Henry, in uniform, aged 18 years. That e-mail opened up, and before I even read the note, I just knew that was going to be Henry's face staring at me! I couldn't believe it! All in one week, here was more information than I'd thought possible – including an amazing portrait of my "mystery" individual.

Another great avenue of research was opened by the two letters of reference included in Henry's Cadet papers. This was the first set of HEIC application papers that I had ever seen, and the same applied to most of the gentlemen on the Victorian Wars Forum (VWF) at the time, since this was before the records were made more readily available. That said, none of us were familiar with the usual form of these recommendation letters. Henry's are very typical, but we did not understand that at the time.

The first letter was written by Henry's father, Lt.-Col. John Henry Pringle of the Coldstream Guards, and reads as follows:

May 13, 1854

I have much pleasure in certifying that since Mr. W.H.W. Pringle quitted the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich back in November last, 1853, he has resided with me, and his conduct in every respect has been perfectly satisfactory.

JHPringle — Lt.Col.

The second letter, was written by Lord Raglan, Master General of the Ordnance, on 3 Mar 1854, saying:

I do hereby certify that Mr. William Henry Wilbraham Pringle was not discharged from the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, in consequence of having been guilty of immoral or ungentlemanlike conduct, or of conduct which would disqualify him from entering or serving in Her Majesty's Army.

Henry wrote a small note along the top of the paper saying, "Was there from August 1851 to November 1853."

When doing research of this kind, it's always hard to keep your imagination contained. It is also very hard to keep from ascribing motives to the people you are researching. Well, sometimes you can't help it, and this was one of those times. It seemed (to more people than myself) that Henry must have left the Academy under "a bit of a cloud." The fact that his only letter of recommendation came from his father suggested that no one else would write one for him, and it was suggested to me that Lord Raglan's letter of approval may have been written as a favor to Henry's father – a gallant officer who was known for his leadership qualities and distinguished career. It did not seem a far jump to the thought that young Henry was less than gentlemanlike and had been removed in disgrace from the school, in order to be packed off to the Bengal Army.

To make matters appear even more serious, his recommendation for the Bengal Army came from the Earl of St. Germans, the first cousin of John Henry Pringle's mother. Even this had the look of being just one more "family favor" to save the face of Lt.-Col. Pringle. It was also suggested that Henry was so poor, academically speaking, that he was not able to continue with the education required and was forced to enter the Bengal Native Infantry – just about the lowest standard of military branches at the time. For a brief time, it almost seemed as if he was going to be intellectually retarded, a thought which seemed corroborated by the discovery that, on his being invalided out of the Army in 1857, the best he could do was to enter Clare Hall at Cambridge (where the "main" subjects were Choir and Cricket). Henry was admitted as a pensioner, which meant that he paid his own tuition, room and board, and thusly had not received any type of scholarship. School records are often a good source of information. Sadly, in Henry's case, this proved to be rather a dead end. He was there such a short time that there is no information about him in the school records of the period outside of his having been admitted, but even that little bit gleaned some information.

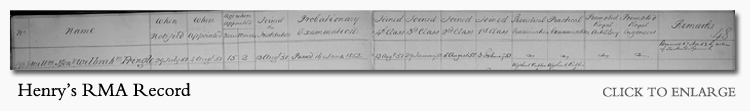

Knowing that Henry had spent some time at the Royal Military Academy, I decided to try for a school record there. This proved more profitable than Cambridge. Henry's record is a short one, containing a few dates of examinations, etc., but it also includes one remark in the last column. This reads simply, "Removed 27 Nov 53 by order of the Master General." A bit of research uncovered the fact that this Master General was the same Lord Raglan who wrote the letter of reference included in the HEIC papers. (As a side note, it's funny to realize that this same officer was also a distant relative of the Pringles by marriage through the Eliots, a fact of which the Pringles were probably unaware.) The idea of "being removed" sounded serious, and it now seemed that there may have been some idea of misconduct going on. Nothing could be nailed down without further facts, but it's not a far trip in the imagination to make up a story using these presumed motives.

It took days of e-mailing with gentlemen on the VWF to even begin to sort out all of this school info. During this time, I continued to go through the online indexes of the British Library India Office collection and came across another reference to a record pertaining to W.H.W. Pringle. I sent an e-mail questioning this record and received an answer back which said that the librarian had "found another more serious report in the record (held at our reference IOR: L/MIL/10/65/643). This record shows that William Henry Wilbraham Pringle was court-martialed on 21 September 1857 for being drunk on duty and under arms. He was cashiered from the army and struck off on 11 October 1857."

This hit me like a ton of bricks! There it was. Solid evidence that Henry Pringle was a dishonourable heir to a long line of honourable officers. It seemed the perfect explanation for his having been removed by the Master General and the reason it was necessary to call in so many favors for the Bengal Army appointment. Henry's story seemed pretty clear, at this point, and I decided to move on to someone else in the family tree.

A month or so passed by, but something kept nagging at me in the back of my mind. Something just didn't feel quite right here, but I couldn't put my finger on just what it was. After deciding to go back over some of the papers again, I realized the main thing that had been bothering me. It was the fact that John Henry Pringle swore at the inquest that his son was "most abstemious, drinking nothing but water". There was no problem in my mind believing that Henry might have been a shameful son, but with the facts that I already knew about John Henry, I could not accept the idea that he would ever have lied under oath. Even if the lie were to save himself or his family any embarrassment, it just didn't fit – so, I decided to send out a couple more e-mails.

The first e-mail went to the archivist in charge of the Royal Military Academy records (the Curator of the Sandhurst Collection). Several days later, a response came back with a simple explanation:

The phrase ‘Removed by the Master General' usually referred to the removal of a cadet from the Academy because he had failed to reach the required academic standards at the end of a particular class of instruction.

This clarification fit in with the idea of Henry's not being particularly bright, but there was still the court-martial record staring me in the face.

Hoping for another opinion, I decided to e-mail the same very helpful librarian at the British Library who had helped me before, asking him to check the court-martial records himself. He responded back that same afternoon, saying that he could find no reference or evidence of W.H.W. Pringle being involved in any proceeding of the type. I sent the quote of the record (as sent to me the previous month by his fellow librarian) and all of the appropriate catalog information to him, asking him to verify that particular record. He did so, and the answer was simple – the other librarian did not know how to read these particular records and neglected to double-check her work. The soldier who was court-martialed and struck off was actually a William Wheeler Jasper Ouseley and had nothing at all to do with young Henry Pringle! The reputation of John Henry and his son had now been restored, and I learned a valuable lesson about double-checking facts which don't mesh with the rest of the story.

In the end, there was nothing more sinister in Henry Pringle's story than a lack of ability to meet the rather "strenuous" academic requirements of the Royal Military Academy. At that time, the RMA only promoted men who had genuine academic ability, unlike the Royal Military College at Sandhurst (for the Queen's Service infantry and cavalry), where advancement was purchased by hard cash, regardless of intellect. The RMC more or less just required that a man be brave and die well while leading his men, but the RMA demanded genuine professional capability. Poor Henry just does not seem to have had that sort of ability, and – rather than embarrass Henry and his father by failing the young man in an examination – the Master General simply "removed" him from the academy.

How heartbroken Henry must have been when, at the age of 17, he had failed to achieve even a small amount of success in a military career. His father was a noteworthy officer in the Coldstream Guards and acting commander of the 6th Lancashire Militia, his grandfather had been a Major-General in the Royal Army (serving in various regiments, including the Coldstream Guards, and fighting with distinction in the Peninsular War – gaining for himself the personal thanks of the House on two separate occasions), and his great-grandfather had been a full General in the British Army with memorable service in the Seven Years' War. Here was young Henry, the oldest son and heir of a family with a great military heritage to uphold, and he could not pass the examinations necessary to make him an officer.

With the favour of his cousin, Henry was recommended for the Bengal Army and entered Addiscombe Academy, the school for the East India Company. Even there, he was only able to achieve high enough marks in the standard subjects for the infantry requirements and not the higher demands of the HEIC Engineers and Artillery (which were arduously similar to the RMA's exams). To Henry's credit, this was not an unusual scenario. Winston Churchill did not even achieve what Henry had been able to do, having himself failed the entry exam marks for the artillery, engineers, infantry and the Indian Army, proving himself to be only suitable for the cavalry (whose academic requirements were the lowest and most basic). Still, this must have been a hard situation to live with as a young man with so much to live up to, as Henry certainly had.*

The fact that Henry was able to pass the initial entrance examination at the Royal Military Academy proves that he was intellectually capable (in an average sort of way), though not capable enough to pass the later exams. He obviously wanted a career in the Military, because deciding on the Bengal Army was a drastic step. Why didn't he opt to enter the Infantry or Cavalry at Sandhurst, where the outcome could have proven quite different, since there was not as much stress on academics there? True, purchase of a commission would have been necessary, but the price of one would not have been an issue for the Pringles. The honourable thought may be that the Pringles refused to take part in the shabby system of purchasing commissions regardless of ability, thereby creating officers who were a danger to their comrades. Besides, there was great room for gallant action in combat and promotion in India, and it may have been a reason like that which made the Bengal Army seem like the best choice, since Henry would have seen ample opportunity to distinguish himself in action. When you're looking to ascribe motives like this, you really need to hope that correspondence or diaries of some sort will surface. Unfortunately for the Pringles, that hasn't happened yet. So, Henry's reasons remain conjecture for now.

Instead of finding a chance for distinction or promotion, however, Henry passed a rather quiet eighteen months in India. He was posted, briefly, with the 58th Native Infantry at Jhelum and returned home in June of 1856 on medical leave. The leave was gradually extended until Henry was forced (in 1858) to relinquish his budding career. (In the end, it proved a bit of a mercy, because he would most certainly have died when his regiment mutinied at Fyzabad, had he stayed in India.)

No family letters or documents have surfaced which would shed any light on Henry's time in the Army. His uniform is probably long gone, and the location of his sword and revolver is a mystery. If his sword was kept, it may have deteriorated in storage. Since two of his brothers served in the military, there is always the chance that both the sword and revolver were used by others. Finally, there is also the chance that one or the other lies hidden in a house or trunk, somewhere in England, just waiting to be discovered. Like the pictures hanging in a country house in an even smaller village in Scotland. Once again, I can't advise enough to keep searching for descendants.

At this point, William Henry had become a "real" person to me, and small details were still missing. Non-essentials, yes; but just I couldn't stop! I still wondered what the family had actually called him, as military and school records always used his three initials. At this point in our journey, the widow of Henry's great-nephew had become a good friend – a friend who continued to go through the house for more clues. It was not until months after the schooling and death of Henry had been discovered that she found an old genealogical chart showing the seven children of John Henry Pringle listed by their pet names (and referring to W.H.W. as "Henry").

Not a week or two after that, one more amazing discovery was made – one that had not even been imaginable. I received an e-mail from this same woman (who had the large portrait of Henry in uniform hanging in her living room), where she wrote that another small picture was attached which might be of interest to me, though I would probably be disappointed, since the painting had a worn spot where some of the paint was missing and was pretty shabby looking. Lo and behold! What I saw was a miniature painting (just inches tall and originally inserted in a leather case like those used for daguerreotypes — though it had long since been removed), from 1836, showing Henry as a small baby in the arms of his proud mother (whose cheek is missing a portion of paint). On the back, in very old ink, was written "W. Henry W. Pringle". A baby picture seemed like the crowning touch, even with a little damage. (It would have been a crowning touch even with a lot of damage.) And it clearly showed the carrot-red hair one expected to find in this family!

Both of these portraits had belonged to Henry's youngest sister, who was only eight years old when her brother had passed away. She had kept them through the decades, and the large watercolour had hung in her house until her death in 1939. She lived to the era of fighter planes over London, but her brother's picture harkened back to the days of the Indian Mutiny! The portrait has been kept and handed down in the family, although Henry's story and name had faded over the years. Just faded, not lost, but waiting for me to come around and drive everyone crazy with questions.

And that is the story of the discovery of one very lost individual in this whole mystery land called "genealogy". What began with a simple name of "Wm Hy Pringle" started a whole avalanche of searches, mistakes and (finally) facts. While Henry may not be the most successful or illustrious member of his family, he's a special individual to me, because no one else (out of the thousands of names in this family tree) has been this much work — and fun — to find.

*As a side note, one of Henry's cousins had the same exact problem of failing at the RMA and entering the service of the HEIC. Sadly, however, this cousin was not spared a brutal murder during the Indian Mutiny.