Edward James Eliot: Form and Character

It was in the months, and even years, after his wife's death that Edward James began to turn his mind, in earnest, to spiritual matters, and it was this period that defined his lasting character. Less than a year after Harriot's death, he wrote to Wilberforce that he had every day less fear of his temper of mind being thought a transitory effect of grief. He felt himself every day looking upon his condition "with more steadiness and resignation, and to a future life with more earnestness and desire." And it is the humble piety and gentleness of this character that endeared him to so many people, keeping their memory of him fresh for decades.

Edward James was a very pretty man (yes, that is the word used back then, although we now prefer "handsome"), inferring that he was not an "under-sized" man — meaning that he was at least five feet nine inches tall by the day's standards. He had the airs and behaviour of the old men of fashion, no longer seen by the 1790s. His hair was on the reddish side (being quite bright and curly as a youngster, while appearing more auburn with age), and his eyes were probably blue or grey, though his surviving portraits have darkened, making that fact a bit difficult to verify. He certainly resembled both of his parents!

Piecing together Edward James' character from various writings proves an interesting and rewarding activity. Apparently, no one ever wrote a concise physical description of him (though both Wilberforce and Pitt made passing mentions of his good looks and "pleasing" exterior), but a fairly accurate character analysis can be deduced from contemporary sources. (For ease of reading, no quote marks will surround the following attributes, but they are all words, phrases, and sentiments applied to Edward James by various friends and acquaintances.)

In manners, he was amiable and promising, with a very extraordinarily good character throughout his life. He had the warmest affections and the mildest manners, was sincere in his friendships, a kind brother, affectionate son, the tenderest of husbands, and best of fathers. His personality was that of a gentle character who loved the shade. From the more ostensible duties of public business he shrank with modest reserve; and, though fitted to take part in them, both by his abilities and character, he greatly preferred the walk of unobtrusive privacy. Though quite active and supportive in the House, Edward James was no public speaker. He chaired committees, acted as teller, drafted proposals and formed many plans, but only two "unimportant interventions in debate" appear on his parliamentary record before 1790. (It does not appear that any important interventions of debate were recorded after that date, either!)

As a young man, Edward James was quite healthy with a naturally strong constitution, but this was undermined by the heartbreak he experienced at the death of his wife. It was a blow that proved too much for him, and he never recovered his former cheerfulness and spirits, nor could he bring himself again to mix in general society. So widely known was the effect of this sorrow, that London papers were still publishing the statement that "Mr. Eliot has not yet thrown off his sables for Lady Harriot" at as late a date as October of 1792. In other words, Edward James continued wearing mourning clothes for the rest of his life (a fact quite noticeable in the Hickel portrait).

After Harriot's death, he maintained a small circle of close friends, most of them family, with the exception of Dr. and Mrs. Pretyman and, of course, Wilberforce. Mrs. Pretyman had been a very close friend of Lady Harriot, so Edward James was able to enjoy private conversations on the subject so dear to his heart with one who shared his loss. He found that there was no relief from his sorrow "except in the Book of God", saying "but it pleased God to sanctify His visitation, and gradually to draw me by it to a better mind." It was during this time of grief that Edward James drew closer to God, being greatly influenced by Wilberforce, to whom he proved an immense help at a crucial time in the great reformer's work. Pitt was not a religious man, and that stood between the two illustrious friends — forming a wider chasm over the years. Eliot, however, never lost his tie to either man, and he formed a never-failing bond between them, being able to discuss and explain motives of each to the other, thereby easing many political situations and misunderstandings.

Anyone who had any dealings with him at all seems to have respected Edward James to an amazing degree — even if they were not on close terms. This general admiration is well illustrated in a letter written by Charles Grant (one of the Clapham-based reformers) to Wilberforce just days after Eliot's death:

"For my own part, though I should, perhaps, never have used the freedom of calling him a friend whilst he lived, yet, now that he is gone, I feel for him with all the sentiments of true friendship."

Even his father's friends were impressed by him, none more so than Rev. John Whitaker (Lord Eliot's friend of many years and a historian of St. German's church), who considered him the "singularly worthy heir" of his honoured father and the Port Eliot estate.

All of Edward James' work now centered around his Christianity. Combined with his general character, the result was a truly virtuous life. He was deeply impressed with a sense of every duty, moral and religious. He was fervent in his faith but unaffected, and in the service of his earthly King and country he was faithful, zealous and able. When it came to charity, he was very bountiful to the poor and active in the promotion of anything which would assist in their relief or comfort. He was "a man, whose singular modesty had the effect of concealing from all but those who were intimately acquainted with him, the superiority of his understanding and the rare qualities of his mind; —in whom a spirit of warm and active benevolence, heightened and regulated by the most elevated principles of action, received a peculiar grace from a disposition naturally the most generous, amiable, and engaging." This tribute was written by Sir Thomas Bernard, an obvious friend and fellow founder of the Society for the Betterment of the Poor. Interestingly enough, a very similar (though not quite so wordy) one was written by Wilberforce, when he told Lord Muncaster that perhaps no one but himself (being Wilberforce) knew Edward James thoroughly. "He was so modest, retiring, and unassuming, that neither in point of understanding, nor of religious and moral character, did he generally possess his proper estimation."

Before moving on from this character examination and venturing into the political and charitable actions of our hero, one more thing should be said. Even though the tributes just quoted were written by personal friends, they were written in the days and months following Edward James' death. It's very easy to amplify virtues of a departed friend or relative, particularly when they die suddenly at a young age. And, very often, this is the real case. While almost all of the descriptive terms and traits mentioned above are quoted from letters written during Edward James' lifetime, there is a world of difference between ascribing a "very extraordinary good character" to a gentleman versus the more flowery tributes above.* To do justice not only to this noble character but also to the integrity of his friends, it's worth noting a particularly beautiful tribute actually written and published during his lifetime.

Rev. Richard Graves was the domestic chaplain of the Dowager Lady Chatham, as well as being a personal friend to the family. He was, therefore, well acquainted with Edward James for a number of years. In 1792, Graves published a translation of "The Meditations" by the Roman Emperor Marcus Antoninus — examples of personal ethics and noble, public-spirited maxims which the Emperor employed throughout his reign. The translator requested (and was granted) the honour of dedicating his work to Edward James, the result of which is a beautiful page of tribute and well worth reading. The first paragraphs deal with the honour of being allowed the dedication, the work of translation and a few remarks on the Emperor himself saying, "He was a philosopher from his youth; and coming to the government of a great empire, at a very critical period, as the love of his country was his ruling principle, so he made its prosperity the chief study and employment of his whole life."

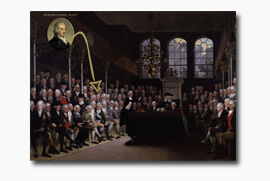

This is followed by a beautiful tribute to our own hero, and it's worth keeping in mind that this was also written during one of the greatest parliamentary eras in British history. There were so many great orators and politicians in the House at this time that the European artist Anton Hickel came to England to paint the House of Commons of 1793. The benches were graced by men like Pitt, Wilberforce and Fox — so there was certainly no shortage of great leaders in the group. Rev. Graves, however, goes on with his dedication as follows:

"In short, Sir, it is, I think, universally agreed, that Marcus Antoninus was one of the best sovereign princes, and one of the most virtuous men of ancient times; and I know of but one sovereign prince in modern times, who can rival him in both those respects; whose effort also for the service of his country, from the instruments employed in that service, will, I trust, be attended, as they hitherto have been, with equal success. I have the honour to subscribe myself, Sir, your much obliged and obedient servant, Richard Graves."

<< Previous Page • E.J. Eliot Home Page • Next Page >>

* To be fair, it's only right in a character study to include all comments (even if they be less than praiseworthy). Amazingly, I could only find one rather derogatory comment, and that by a relative (sad but not surprising, given the sour nature of the author). The remark was put down on paper in 1783 by the rather venomous hand of Edward Gibbon (famed historian and first cousin of Edward James' mother), when he called his cousin's son a "very unmeaning youth". This was said on the occasion of Edward James being appointed a Lord of the Treasury and his father being raised to the peerage. Gibbon was a personality who liked his relatives only for what they could do for him, and he resented his cousins' wealth and prosperity. Consequently, the Eliots were a common subject in his letters, and he used many vindictive terms in regard to them every time they did not live up to his expectations of supplying him with a gratis income.