The Pitt Connection

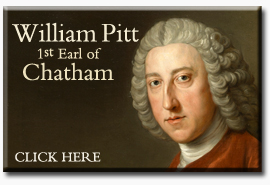

In 1785, Edward James Eliot (son of 1st Lord Eliot) married Lady Harriot Pitt, sister of William Pitt the Younger. Through the birth of their daughter, the two families were forever tied by blood. The Eliots' connection with the family of William Pitt (Earl of Chatham) had begun much earlier, though. The first recorded instance of this friendship dates back to about 1732, when Harriot Eliot (nee Craggs) was nineteen years old and already mother of three children. Harriot later described the occasion to her daughter (Mrs. Anne Bonfoy), who later related the story to her niece, Harriet Hester Eliot.

"Mr. Pitt [William the Elder], being one day in company with Mrs. Eliot, in a house in the country, withdrew from the conversation to an adjoining window, and being asked by her what he was doing, replied, 'Drawing your picture, Madam;' and immediately recited these verses:

To view that airy mien, that lively face,

Where youth and spirit shine with easy grace,

We form some sportive nymph of Phoebe's train,

Some sprightly virgin of the sacred plain:

But --- lo! a happy progeny proclaim

Love's golden shafts, and Hymen's genial flame.

So the gay orange in some sylvan scene

Blooms fair and smiles with never-fading green,

Her flow'ring head with vernal beauty crown'd

Speaks tender youth and sheds perfume around,

While fruits ambrosial deck the lovely tree,

The heavenly pledge of blest maturity,

In pleasing contrast with surprise we sing

The fruits of Autumn and the bloom of Spring."

Between 1773 and 1780, both Edward James Eliot and William Pitt the Younger attended university at Pembroke College, Cambridge. By 1782, the two young men (already serving in the House of Commons) were partners in the fight for Parliamentary Reform. In July of that year, Pitt, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, gave Edward James a seat on the Treasury Board (making him a Lord of the Treasury), strengthening the bond between the families.

Pitt and Eliot (joined by another Cambridge friend, William Wilberforce) decided to journey to France to spend five or six weeks improving their knowledge of the French language. On their return from France, in the autumn of 1783, Eliot and Pitt privately prepared for major governmental changes. When the coalition of Fox and North fell, on 19 Dec 1783, William Pitt became England's youngest Prime Minister.

One of Pitt's first acts as Prime Minister, in an effort to secure his political position and strength, was to raise several MPs (all of whom were his friends or sons of friends) to the Peerage. Each man controlled multiple seats in Parliament and was (or suddenly became) a staunch Pitt supporter. In January 1784, Edward Eliot (father of Edward James) "kissed the King's hand" and was given the title of Baron Eliot, bringing six Cornish seats and a family's lifetime devotion to Pitt and his followers.

The Marriage of the Eliots and the Pitts

Harriot was the older (and most-beloved) sister of William Pitt the Younger; she often stayed with him at his home at 10 Downing Street. Speculations of an "attachment" between Harriot and Edward James Eliot were published in the early months of 1785, and, in April, Eliot wrote to inform his father of his upcoming marriage.

Lord Eliot objected to the marriage, convinced that his son did not have sufficient income for the support of a family and should wait for an Uncle's death which was expected to bring a large inheritance to the Eliot estate. Edward James, however, had no such concerns, and wedding arrangements proceeded as planned. William Pitt did not have any money to settle on his sister but did have the power to raise Edward James to the position of Remembrance of the Exchequer – with a salary of £1,500 per annum. This calmed the troubled waters, bound the Pitt and Eliot families "for better or worse", and the Hon. Edward James Eliot married Lady Harriot Pitt (on 24 Sep 1785) at the Putney home of William Pitt.

The marriage ended in tragedy, however, with Harriot's death on the day after their first anniversary, just five days after giving birth to a daughter. Eliot never recovered from the loss of his wife and remained for years at 10 Downing Street, unable to move from the house where he had been so happy. The sorrow brought Eliot closer than ever to his Pitt in-laws. His infant daughter was raised at Burton Pynsent by her grandmother, Lady Chatham, where the devoted father often spent weeks at a time. Even Eliot's choice of guardians for his daughter – Lady Chatham, William Pitt, John Pitt (Earl of Chatham and brother of William) and George Pretyman – portrays the high degree of connection between the families.

The Eliot-Pitt Political Connection

The Eliot brothers, Edward James and John, were virtually inseparable from Pitt, so much so that it is impossible, in many cases, to discern which "Mr. Eliot" is referred to in newspaper reports of the day. For instance, on 12 Nov 1796, the following report was published in "The Times": Mr. Eliot, who was in the carriage with Mr. Pitt on Wednesday when he went to Guildhall, was considerably hurt on the head by a stone thrown into the carriage. John Eliot rented and/or owned several houses in London, including 11 Downing Street. William Eliot, deeply attached to his oldest brother and a staunch political supporter of Pitt, later shared a high degree of this close family fellowship and spent a lifetime voting as he thought Pitt would have advised.

Edward James Eliot was involved in every aspect of Pitt's government, was privy to the most private plans and decisions, and served as a member of the government throughout his entire (albeit short) adult life. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of Edward James Eliot's knowledge and involvement with Pitt in government was recorded by Mrs. Elizabeth Pretyman, wife of George Pretyman (private secretary to William Pitt) and personal friend of Edward James and his wife. She wrote the following account in November 1801 (which was edited into its present form by John Ehrman, in his biography, "The Younger Pitt").

In 1796 and 1797, things were critical for the Country, Bank of England, naval mutiny, &c., and Mr. Pitt, ever ready to sacrifice himself for what he thought the good of his Country, had serious thoughts of resigning his situation, hoping the French would make peace with another Minister rather than with him. We were at Buckden while this idea and consequent plan was upon the Tapis. But we heard constantly from Mr. Eliot. Details could not be mentioned in letters, and this plan was of a nature too delicate to be trusted to the Post.

We knew nothing of it therefore till we went to Town which happened to be two days after it was given up. Mr. Eliot came to the Deanery an hour after our arrival. The Bishop was engaged with a person upon business and Mr. Eliot afraid of not being in time for the House of Commons told me the whole surprising Story before the Bishop came up. He told me what I have related, of Mr. Pitt's idea and proposal, and that he thought he could make a very tolerable Administration without himself and a few others so as to keep Fox and the Jacobins entirely out. Upon my asking eagerly "who could be found as Mr. Pitt's Successor", Mr Eliot answered, "Addington".

Mrs. Pretyman was astonished. "Addington!" (exclaimed I instantly) . . . "Are you all mad?" and, so she claimed later and probably truthfully, said that she distrusted him. But Eliot was unperturbed. "Oh no," he answered her (smilingly), "Addington would do very well under the direction of Mr. Pitt, for a time. It would not do forever, but it would do Mr. Pitt good to be out of Office for a little while." . . . "But [he continued] you may make yourself easy, for the thing is not to be. Everything is now settled and we are to remain as we are. The Storm is over." "Does Addington know what was intended?" Mrs. Pretyman asked. "Yes.". "Does the King know? Did it go so far as that?" "Yes, he certainly did not like the Change, but what could he do if the present Ministers thought it necessary?" "Did Addington readily agree to the new Arrangement?" "Certainly. How could he do otherwise at Mr. Pitt's request? He owes everything to Mr. Pitt, and Mr. Pitt would have directed had he taken the situation, so that he would not have been under great difficulties. Besides, I really do not think so ill of his abilities . . ."

The Death of Eliot

Edward James Eliot was not healthy for the last years of his life, suffering from a recurring illness, often referred to at the time as an "affectation of the stomach". Complaints of this kind had been common among the Eliot family for the past two hundred years (possibly due to the foul water lapping at their door and the active cemetery lying outside the dining-room window), and the effect of his wife's early death reeked havoc on Edward James' health.

Eliot had been struggling with his final bout of illness since the beginning of 1797, even spending some weeks at Bath, hoping the "pump water" would have a positive effect. His poor health continued, however, and Eliot was forced to refuse an appointment as Governor-General of India. Before the summer was out, he left the business of London and went to stay with his parents at Port Eliot. The news of his death reached Pitt at Downing Street, in the morning mail of September 20th (three days after the melancholy event). Pitt's reaction to this saddest of news was described in a letter to Wilberforce by George Rose, Pitt's secretary and friend:

"The effect produced on Mr. Pitt was, as you may imagine, beyond description; it has not happened to me to be a witness of such a one, as I saw him immediately after his getting Lord Eliot's letter by the common post, and reading it among others, not knowing the writing; it is difficult even to conceive the impression made by the misfortune, and the manner of hearing of it. To say that from the bottom of my heart I lament the loss, is poorly expressing what I feel; I can say truly that in my intercourse with men I have met with few, very few indeed, such as our poor friend was. The poor little girl was with her father, so was John Eliot; William is at Trentham."

He went on to say that the blow of Eliot's death was one of the very severest that could have been inflicted on poor William Pitt. Wilberforce wrote that the effect of the news on Pitt "exceeded conception". Pitt wrote a short note to Addington, that same day, saying:

"I am grieved indeed to tell you, and you will, I know, be grieved to hear, that a return of Eliot's complaint has ended fatally. The account reached me from Cornwall this morning, at a moment when I was quite unprepared for the event. You will not wonder if I do not write on any other subject."

In fact, the shock of Eliot's death brought on a severe recurrence of Pitt's own health complaints, and it was some time before he was able to conduct his full load of ministerial affairs, causing his many friends much concern.

William was not the only member of the Pitt family to be distressed by this news. Lady Chatham (Edward James' mother-in-law) was recovering from illness at her home, and it was up to her longtime friend and companion, Mrs. Stapleton, to decide how to break the news to her. Six days later, John Pitt, Earl of Chatham, wrote to Addington:

"Many thanks to you for your kind letter and for the concern you express at the misfortune which has befallen us. I was much shocked at it, though I cannot say that I was unprepared to expect it, as from what I knew of poor Mr. Eliot's complaint. I was very apprehensive of the worst, the moment I heard of the frequent returns he had had since he left town. I have great comfort in being able to answer satisfactorily your concerns about my Mother. Every precaution was used in communicating to her the melancholy intelligence from Port Eliot, and she suffered as little as under so severe a blow could be expected. I fear however it will retard the progress she was before making in recovering [from] her late illness. I had a few lines from her yesterday, wrote tolerable composed, and Mrs. Stapleton assures us she has not suffered materially. My Niece is tolerably well."

The Pitt-Eliot Connection Lives On

After the death of her father in 1797, 11-year-old Harriet Hester Eliot went to live at Burton Pynsent, with her grandmother. The "poor little girl" had been raised there as an infant and had spent many months at this house with her father, so the surroundings would have been a comfort to her. Not six years later (in 1803), Lady Chatham died, and the orphan went to live with her uncle, John Pitt, in London. It was from his house, three years later, that she married Lt-Col William Henry Pringle.

This tight-knit Eliot-Pitt family connection remained in effect for the better part of a hundred years, long after the death of both William Pitt and Edward James Eliot. Harriet Hester Pringle was obviously very proud of her Pitt connection and passed that pride on to her children. Her son, John Henry Pringle, was strongly attached to his Pitt relatives throughout his life and inherited a good portion of John Pitt's estate. As joint heirs of the Earl of Chatham, John Henry and his Pitt cousin (William Stanhope Taylor) edited and published "The Correspondence of William Pitt" in 1840. It was John's son, Rear-Admiral Eliot Pringle, who donated all of the Chatham papers to the Public Record Office in 1888.

More than two hundred years have passed since Edward James Eliot and William Pitt became friends and brothers, but the given names of Eliot, Pitt and Grenville can still be found among current descendants of Edward James and Harriot. Various Pitt family items were passed down through the Pringle line, including a chair made of wood from the HMS Victory and presented (after Trafalgar) by "A Grateful Nation" to William Pitt the Younger; Chatham Armorial China; a large, mahogany, Georgian Writing Desk having belonged to the 1st Earl of Chatham in the mid-18th-century (commonly referred to by the family as "the Chatham Chest", last having been used in the 1980s as a descendant's tool chest); William Pitt's "Order of the Garter" Robes; and a stack of prized letters written by Lady Harriot Eliot (nee Pitt). All of these items (and, undoubtedly, many others) have since been donated, sold or remain secreted in family homes. Descendants of Edward James & Harriot (Pitt) Eliot are still many, living in many countries and bearing many surnames.