Henry Cornwallis Eliot (1835 - 1911)

Henry was the seventh child and fifth son of Edward Granville Eliot and Jemima Cornwallis.

When the Western Morning News, a local West Country newspaper, asked the 5th Earl for personal information and anecdotes from his own life, the Earl's response must have been as disappointing to them as it is to modern researchers:

"I am sorry to hear that you are thinking of publishing a sketch of my life, as it can be of no public interest. The dates of my birth and marriage, &c., will be found in any book of reference, and also the fact that I was five years in the Navy and 26 in the Foreign-office. I really do not see what more there is to say about me."

The few facts that can be gleaned from books such as "Burke's Peerage" and "Who's Who" are pretty much all that has been remembered of Henry for a long time. Like Henry himself, during the first years of my association with this family's history, I considered him to be one of the "most boring Eliots". Peregrine (10th Earl of St Germans and my friend) had a particular fondness for this ancestor, though, and pestered me time and time again to look into "the Victorians". While my interests drew me to the Eliots of the 18th century, Peregrine kept trying to drag me into the 19th. "But he was in the Navy!" he'd say. Years went by, and I continued to resist his best efforts to cross into "modern times". In the end, however, it was General G.A. Higginson who broke the time barrier for me. An odd little online search brought up a small paragraph from the General's 1916 autobiography, and Henry's story exploded into a massive project of prime interest to me.

Far from being the most boring Eliot, Henry Cornwallis, 5th Earl of St. Germans, led quite an interesting life and turned out to be one of the most beloved members of his family – respected, revered, and remembered by his friends, tenants and employees . . . and me. A large number of his boyhood letters (carefully preserved with the rest of the family's correspondence) provide a fascinating and intimate look at a young fellow growing up in the 1830s and 1840s. A regular little boy who loved to read (particularly Mr Dickens), eat ("more meat pies, jam and sugar cakes"), fish, swim, play and ride. His general health was good, and he got through the measles without too much trouble. As a little bloke, he absolutely doted on Mr Sainsbury (Gamekeeper at Port Eliot), with all of his chickens, dogs, kittens and ponies (a love which did not die even upon Mr Sainsbury's death). He played with his brother's "conjuring set" and loved anything to do with scientific experiments. Henry and his siblings spent happy days exploring the underground tunnels at PE near The Craggs, entertaininging themselves with many thrilling "smuggling adventures". His family's deep-abiding love for each other was shown in every word of their letters, and it ran deep in Henry's veins. He looked up to his sister and older brothers and doted on Baby's every move and word.

As a boy, Henry had a passion for riddles and socializing. He was thoughtful of other people's feelings and well-being and "never met a stranger", as the saying goes. Throughout Henry's letters, there is this overwhelming feeling that he thought everyone was as glad to see him as he was them. Like every one of his Mother's children, he had a capital grasp of "modern" slang. He had remarkable manners, a strong sense of self-confidence, and a kind word to say about everyone. He loved adventure and ever-changing scenes, was easily bored and easily distracted/amused. (More than a day or two in one place and Henry began to feel that the place was "stupid" – the 19th-century word for bored and one of his favorites.)

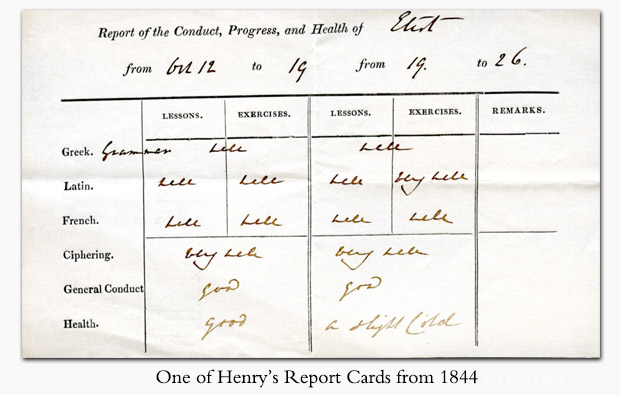

Henry was proficient in "ciphering" and languages at an early age, receiving high marks in Latin, Greek and French before his 10th birthday. His report cards were always excellent . . . in most areas, anyway. There was one less-than-perfect mark, though, and that was handwriting and spelling. (His teachers commented on it, but a quick look at his letters was all you really needed. Ironic, isn't it, since his lifelong career was that of a Clerk at the Foreign Office?) At the same time of his boyhood, he was familiar with all of the London theatres and loved a good play. He came by this honestly, of course, since the Eliots throughout recorded history have been potty about theatricals and entertainment, from both sides of the footlights. He was very fond of swimming, ice skating and all other outdoor sports of the time. A six-month schooling in Paris during 1847 found him studying German and Spanish, with fencing lessons three times a week. Henry did not care for Paris much, but his stay was short, and – as always – he made the best of the situation.

Henry was just a little chap when he decided on the Navy. It seemed to hold the key to all of his dreams. In 1848, at the wise old age of 13 years, after a preparatory education at a private school and Eton, he set sail aboard the "Prince Regent" as a Cadet in the Royal Navy. He was off to visit some of those faraway places with the strange sounding names, very proud of the fact that he never suffered from seasickness. A day or two in each place was about all his short attention span could bear, but he admirably performed his duties at all times. He accidentally lost the sword given to him by his Godfather and outgrew his uniforms as quickly as they could be made. (That boy must have spent the first 20 years of his life HUNGRY! He didn't like salt junk, and thought the Navy victuals "unpleasant".) Nevertheless, the Navy suited him just perfectly; his half-yearly allowance from his father was £30, and he did his best to live within his means. But poor Henry! At the age of eighteen, after only five years in the service and having made Midshipman, his hearing began to deteriorate at a rapid pace. Despite anything that doctors could suggest, his condition worsened, and he was forced to resign and return to England.

It was now 1853. Henry's sister had married while he was gone, so there were nephews and a niece to meet in England. Most of the next year was spent, however, at the Vice Regal Lodge in Dublin, where his father was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and his parents entertained in a most lavish manner. (Henry's Mother was known as a most perfect hostess and organizer, and many of her balls were legendary.) He was proficient at the "regal behaviour" expected of his Father's son and never missed a chance to dance. He attended all the balls and dinner parties and became intimately acquainted with the best of the 1850s upper echelon in England and Ireland (although he admitted to having a poor memory in general, in particular for names and faces). We know of at least three young women whose hearts belonged to him, and Olivia, "Bunty" and "The Star" live on in family letters, their unrequited love as fresh as ever. One of these society beauties, in fact, is the reason for his next move in life.

Henry's parents felt the necessity of Henry's separation from a certain young lady. They sent him to Egypt and India, alone, on a rather unusual form of a "Grand Tour". (Henry would later write that he thought "the reason for my banishment was Olivia", when he discovered that it had really been "Bunty", who had tenderly remarked to his Aunt that he was "too precious" to be exposed to danger). His two oldest brothers had taken the same route a few years before, so Henry was eager to relive the experiences which they'd related in their letters. At first, the excitement of travel and shooting expeditions pleased his insatiable need for change and adventure. He even wrote to his brothers of climbing a pyramid and carving his initials near the top! But after months of this lonely travel, Henry's letters began to fill with a longing to be with his parents and siblings. Wandering around India on elephant-back, looking for tigers to shoot, began to lose its thrill. As Henry had never exhibited a very long attention span before this, it was no surprise when he began to plan for the trip home earlier than expected. But it wasn't time. Not yet.

England was readying for war in the Crimea, and Henry's brother, Granville (Captain in the Coldstream Guards), was already at Scutari. It seemed a grand lark to Henry to visit Granville in the Army's camp before returning home. It was early June 1854, and their Father granted his permission and extra funds for the extended travel, relying on Granville to keep his brother "out of trouble". Most of their Father's staff (military men all and Henry's closest friends in Ireland) had already arrived in Turkey, but it wasn't enough to keep him there long. Henry missed life at Port Eliot, and the disorder and dirtiness of Army/Navy life in the Crimea seems to have quenched some of his ardour for adventure. Watching battles from the heights or ships in the harbour began to lose its thrill. He was faithful in his writing and sent home reports of the battles of the Alma and Balaclava. Henry treated the early days like a diverting look at exciting places in a "filthy, dirty" land. He made little of the privation they suffered (though he often yearned for a "good bath"). Henry was capable of finding a bit of fun in most situations; but things, in general, weren't moving fast enough for him, and he began planning his return home.

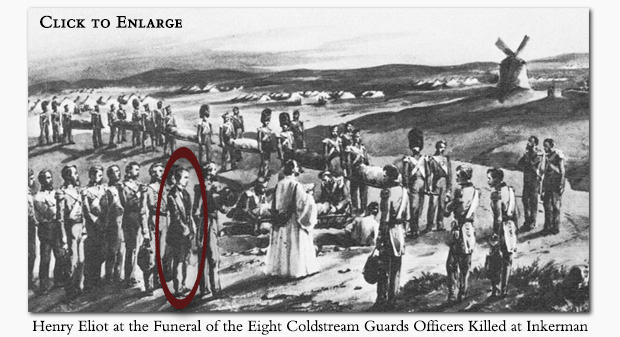

The fun ended suddenly on November 5th. It was on the battlefield at Inkermann where Higginson found Henry standing over the body of his beloved brother, killed by the Russians just minutes before. The battle still raged, and Higginson's vivid memory of this scene was what had grabbed my attention in that online search.

Henry was crushed, barely able to write the letter home to tell his father the terrible news. He stayed for the still-historic funeral on Cathcart Hill of the eight Coldstream Officers who died in that one fierce battle (including his brother, as well as the other seven officers who had grown to love Henry in the time he'd been with them). With a sorrow that seemed impossible to bear, he gathered his brother's few belongings and returned home as soon as possible, carrying the emotional scar of that awful day for the rest of his life. (He brought home a lot of battlefield and local "souvenirs", too.) His homecoming was a thing of joy, to be certain, as so many sons were not returning home in those days. The joy was dampened, however, by the overwhelming grief permeating the very air of the country, and the shock of Granville's death was too much for his Mother. She would die not two years later, of a broken heart, in the same week that the surviving Coldstreams returned home to London. The Crimean War had changed life forever for the Eliots of Port Eliot and their dearest family and friends. The familiar faces of loved ones were gone, now memorialized by bloodied uniforms and hastily scrawled letters from the fronts in Turkey. Life went on, of course, but the paths had changed forever.

In one short month, Henry's life took a complete turnabout, and he quickly settled into a quiet, unadventurous career as a Clerk in the Foreign Office. Now in his twenties, he swiftly became one of London society's "most eligible bachelors". Family connections offered him entree into all of the best circles; and dances, dinner parties and the opera (all of which he was absolutely potty about) occupied his free time. Sadly for us (Henry was probably thrilled), his quiet life in England meant that he didn't need to write letters to his family. The 1860s become a bit of a "dark ages" in our story. His oldest brother died in 1864. The newspapers reported his attending dances, dinner parties and the opera ad infinitum. Still interested in everything for the first time, Henry flung himself into the maddening pace of the post-war social world. He had seemingly had his fill of adventure, and his life became one of unvarying days and months. Until 1870, that is, when a new chapter in Henry's life exploded onto the scene, right before his very eyes. Literally.

Even though closed off to him as a career, Henry never lost interest in anything connected with the Navy. His closest mates from Midshipman days remained lifelong friends. In November 1870, Henry and his brother were invited to view a naval gun experiment at Devonport (not far from Port Eliot), but it all went wrong. While the brothers were on deck, viewing the proceedings, the discharge of the experimental torpedo caused a nearby window to break and shower glass all over Henry's head, severely cutting his face and causing the loss of his left eye. At 35, poor Henry was now practically deaf and needed a glass eye! (Peregrine had always heard there was "an Earl with a glass eye", and the discovery of the story made him almost giddy with childish pleasure.)

Henry had the amazing gift of being able to find something positive in every situation and was not one to let problems slow him down. He returned to his desk in London at the Foreign Office and continued to indulge in two of his favorite hobbies: shooting and billiards. Henry was known far and wide as a crack shot at both sports — mentioned by the local newspapers as if it were a well-known fact that bore repeating. During quiet times or bad weather, Henry enjoyed Whist, flatly refusing to attune to the times and learn the "modern" game of bridge. (The Eliots of Port Eliot had always been known to be "a hundred years out of time".)

Holidays were spent away from London, at the much-loved PE, as the family called it. In 1872, the first Christmas tree in St Germans was erected by Henry's father in the town hall at St. Germans. Christmas at PE was the highlight of the year for this family. The anticipation of the seasonal festivities was enough to gladden their hearts, and friends and relatives came from far and near to share it with them. These celebrations were very like ours nowadays – gifts, theatricals, games, a Christmas dinner, and Christmas service at the church. The Eliot cheer didn't stay at home, though. St Germans villagers received gifts as well (e.g., large-scale teas or distribution of meat and other commodities, dependent on their needs that year). Henry was in his element at Port Eliot – good friends, good food, and the family he loved.

Time passed, and death visited the Eliot family three times between 1864 and 1877, including two older brothers and his father. At the age of forty-six, Henry became the 5th Earl of St Germans. It must have been a sad time for him, like so many other inherited-title holders experience; his rise in life and succession to the estate was only possible because a loved one (or four, as in Henry's case) "departed this life" to make way for the new Earl. In Henry's case, it was the best of fathers and a beloved brother who died within four years of each other. (As the fifth son, Henry cannot ever have imagined that the estate would come to him, but time would show that he had been born for this task.)

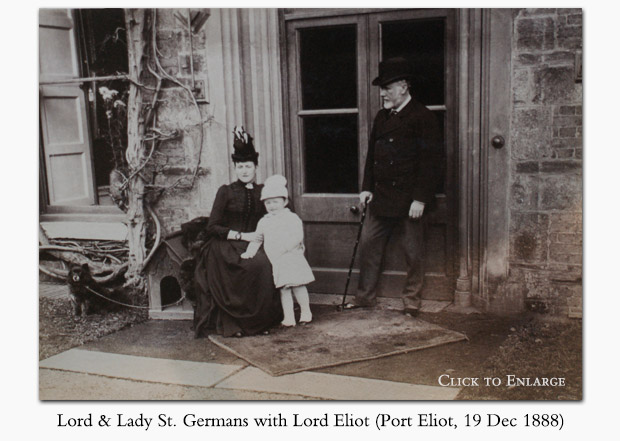

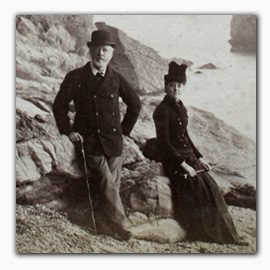

Always the man to "ride the waves", Henry retained the title of "bachelor Earl" for only a few months. His wedding to the Hon. Miss "Lily" Labouchere followed later that same year, and the happy pair settled into a busy life at Port Eliot – raising their two sons, renovating the church standing just outside their windows, and supporting a vast number of charities and institutions. They endeared themselves to their tenantry like no other Earl and Countess before or after them and left their mark on St. Germans in ways that survive even today. There were lawn fetes for charity, shooting parties and visitors galore, and lots of nieces and nephews coming "home to PE" at all times of the year. Henry's older sister and younger brother and their families were dearly loved and welcomed to PE often, not to mention Lily's two sisters and their families. The Eliot family bonds would never be stronger than they were during Henry's lifetime, and he thrived in this atmosphere. (In an amusing side note, a friend of Lily's later wrote this about the happy couple: "I was delighted to see again Lily LaBouchere, supremely happy in married life, as Countess of St Germans, with her excellent husband. She had found him when he was 50, and though he was the color of a poppy and had only one eye and was deaf, their union was blessed by a son and heir some years later.")

In 1903, Henry suffered his first stroke but recovered well, though it would seem that it was the end of his dancing days, since no more reports featured him leading the first dance at the annual Port Eliot Servants' Ball. His younger brother had been gone for two years, and he must have been quite lonely for his lost brothers, having only his sister left who "remembered when". His brother Granville's blood-stained coat (the one he died in) and four-clasp Crimean medal were on display in a glass case at Port Eliot, and Henry enjoyed inviting friends of his brothers to shooting parties, listening with keen interest to anything they could recount about the old school days. He spent his last years cataloguing the family's massive art collection and began the enormous work of sorting and dating the large boxes of letters saved in the muniment room. (N.B. Henry's handwriting may have been spidery and weak, but years in the Foreign Office must have improved what he thought was a bad memory. Many of the family's letters were undated, so he pencilled in the missing dates. After having read through hundreds of these letters and researched people/places mentioned in them, I can tell you that not one error was made by Henry in those dates. And some of the letters were written by the Eliot children 60 or 70 years before he worked on the sorting of them. Very impressive.) His sons grew, and time passed. In 1906, Henry and Emily marked their 25th Wedding Anniversary and Lord Eliot's "Coming of Age" in one lavish celebration at PE. It was to be the last of the celebrations of its kind at Port Eliot, and the old Eliot traditions were gone for good.

Tragedy struck the family in August 1909. Henry's older son and heir committed suicide in the gun room at Port Eliot. It was a rainy day, and the cricket players upstairs had decided to cancel the scheduled game and sit down to a companionable lunch. Eliot's death was more than his father could bear. Henry's health declined for two more years, when the final stroke ended his life in September 1911. The county was devastated by his passing, and testimonies of his character were published in many newspapers. The Royal Cornwall Gazette published these words:

"There is not one in this parish who does not but feel that he has lost a very great friend," was the testimony of Canon Westmacott at St. Germans parish church on Sunday when alluding to the decease of Earl St. Germans, which took place that day. That is a high tribute to any man; but it is one that can be applied to the deceased earl, not only in his relations with his fellow parishioners and those who lived in the immediate locality of Port Eliot, but in regard to the Earl's relationship with all who had his acquaintance in whatever rank in life. . . . The late Earl of St. Germans saw less of public life and service, perhaps, because of his serious affliction of deafness and the partial loss of sight; but as a friend and a neighbour he was, to use a Gilbertian phrase, "The embodiment of everything that's excellent." Kind, generous, unassuming, full of desire to help whatever institution he could for the betterment of the condition of those around him, he played a quiet but by no means unimportant part in the circles in which he moved and the neighbourhood in which he lived.

Hardly the praise you'd expect for the "most boring Eliot" in the family tree! When you read about the different Earls of St. Germans and Squires of Port Eliot, there are three who were loved above all and esteemed by the tenantry in a special way (the "noble Earls") — they were Henry, his father (3rd Earl), and his grandfather (2nd Earl). And now the last of the "noble Earls" at Port Eliot was gone, never the like to be seen again. Many mourned his passing, but they all remembered his Christian spirit and charitable nature. Henry Eliot is an Earl worth remembering. Peregrine was right, after all . . .

Photos of the Silver Wedding Celebration mentioned above were taken, as well as extensive reports written for the local papers. Click on the buttons below to view the photos or read the articles.

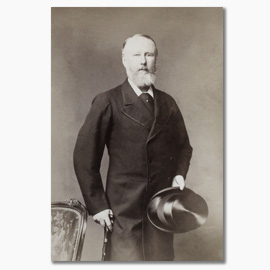

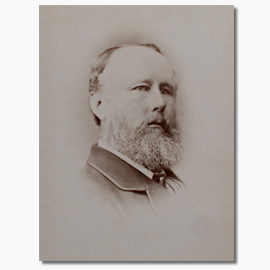

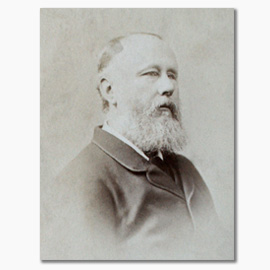

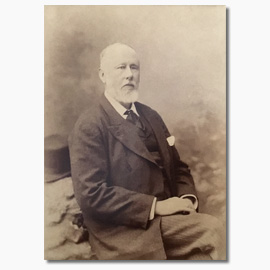

Four portraits of Henry Eliot are still in the family collection at Port Eliot – the earliest being a small watercolour by an unknown artist in the 1840s. A small miniature by an unknown artist shows young Henry Eliot in his Eton suit (c. 1845), and the family art catalog records a portrait from a similar time by Cornish artist, Nicholas Condy (either the father or the son). The last portrait is a larger one by Edward Opie (painted c. 1879), one of a pair – the other portraying Henry's younger brother, Charles. The Eliots were very keen amateur photographers, so many photographs of him survive in the family albums.