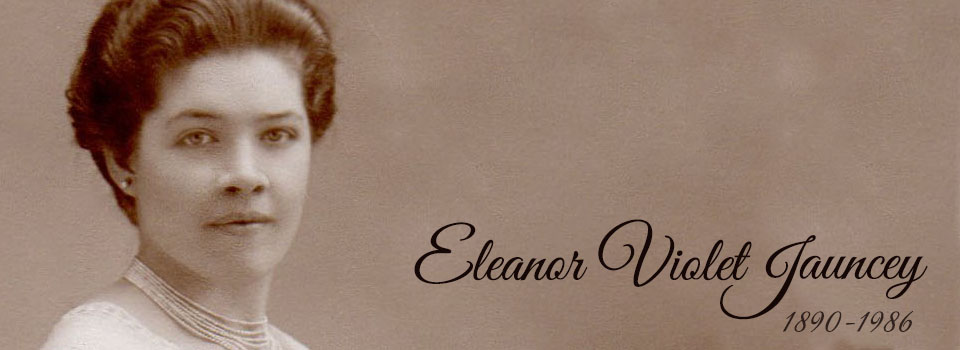

Eleanor Violet Jauncey (1890 - 1986)

Eleanor Violet was the fourth child and only daughter of Henry Jauncey and Blanche Pringle, known to family and friends as "Eleanor" and "Va".

Eleanor Jauncey is one of the most intriguing personalities to surface in the history of all the descendants of the Eliot family of Port Eliot. She never went to St. Germans or saw the great house there, but she was the great-great-great granddaughter of the first Lord and Lady Eliot. On paper, from a genealogical research point of view, poor Eleanor doesn't look very interesting. In fact, her "biography" boils down to the following few rather dull facts. She was born in Surrey in 1890, seven months after the death of her father, and grew up with her mother and one surviving older brother. She died in Scotland, never having married, at the age of 95. That's about all you'll find, if you only search the genealogical databases. Search just a little harder outside those sites, though, and you'll find that Eleanor was a member of the Ipswich Fine Art Club from 1919-24 and that she worked at Bletchley Park during WWII. There it is. Ninety-five years boiled down to a few sentences. She didn't get her name in the papers. She didn't even appear in all the UK censuses . . . but this is a fabulous example of how much history is lost every day, and every researcher or historian has their own "Eleanor Jauncey".

Studying history and researching individual people is just as intricate an undertaking as it can be interesting. In most cases, it is impossible to get any idea of a person's actual character and personality. The deeper into a project you get, the easier it is to turn people into names and dates on a piece of paper (or in this age, names and dates in a computer program), but the real story of those names is lost. However . . . every now and then, a fabulous breakthrough occurs, and you catch a glimpse of the personality behind one of those names on your list. Like Eleanor Jauncey.

When she was 94 years old, Eleanor's niece asked her to remember her life and write down anything that came to mind. By this time, "Aunt Eleanor" was living in Dalginross House, a home for the elderly in Comrie. Picture her, if you can. She looked like any old lady in the 1980s, grey hair and an unassuming demeanor. A diminutive figure seated in a worn chair, balancing a pad of paper on her knee, scrawling out her precious memories. Memories which must have been, by the way she told the stories, as fresh in her mind as if they had been recent events. Memories which took her back to happier – and sadder – times. It seems obvious that family photos were used to jog her memory (if it needed jogging, which cannot have been often), as many of her remembrances have corresponding pictures. Memories which were not stories as much as a retelling of emotional moments which had shaped her character. Like many elderly people, what surfaces from Aunt Eleanor's scribblings is a clear picture of the strong emotions which live in the hearts of all people. She records neither genealogies nor unrelated facts (and as to these, she is not often very attentive). She did not preserve relationships of the people involved in her stories; nor did she bother to remember things in any chronological order. Indeed, what she so vividly remembered were events which had left a lasting impression on her mind and heart. Not quite raptures of delight or depths of sorrow, but something more elusive. Something softer and far more able to transport you into the world of a three-year-old girl playing with her dear little Droujok or a 27-year-old woman trying to deal with the murder of her dearest cousins in Russia. You feel her joy at finding the little "St George and the Dragon" with her kind Uncle Serge on their companionable shopping trips in the dark little second-hand shops. Conversely, you later feel her disappointment in the manner of its disposal. You are carried away, with a little imagination, at this little old lady's remembrance of the Prince with whom she so felicitously glided across the dance floor to the tune of the waltz. You climb the Alps and cross the hazardous waters to the Blue Grotto of Capri. More, so many more, memories like these, and yet nothing in the outward appearance of Aunt Eleanor to suggest the wealth of experiences she'd lived through in her lifetime. A life that had begun in the last decade of the Victorian era, experienced the high society of Europe in the days preceding the Great War, contributed to the Allied victory during the second World War, and helped raise much-needed funds for the little parish church by selling flowers at her makeshift stand. She was one of the last survivors of an era and way of life that is now left only to be discovered by pouring over the endless stream of tired and rehashed history books. This is a fabulous example to prove the old saying, "Don't judge a book by its cover!" A person may appear old and uninteresting, but the wealth of knowledge and observations they have to offer does not diminish with the passing years, and too often that wealth is lost for lack of interest on any listener's part. Thanks to Aunt Eleanor's written memories, a picture of her life and that long-ago era survives which leaves in its readers the feeling that it might have happened yesterday, instead of a hundred years ago. You are left with the understanding that people were the same then as now — they just wore different clothes.

Add to these memoirs some written notes about Eleanor by her great-nephew, and you get an amazing picture of her as a real person with an individual personality, including her likes and dislikes. She may have looked like a "little old lady" during the last decades of her life, but she had a richer life story than many wealthy or titled people could claim. She was raised by a mother who was old-fashioned, a classic picture of the early Victorian era; and Eleanor was one of that last generation to carry the Victorian characteristics into the end of the 20th century — a survivor of days gone by.

Memories of Eleanor Jauncey, by her great-nephew Jamie Jauncey (36 years old when she passed away).

• Rosy apple cheeks.

• A rope of braided grey hair coiled up on her head.

• Long tweed skirts, woollen stockings and brogues.

• Feeding sticks then coal into the little stove (or was it an iron grate) in the tiny cluttered kitchen.

• Tales of childhood visits to Russia and games with ivory spillikins and miniature patience cards.

• Scented tea in chipped bone china.

• A fierce independence of spirit and an open, curious mind.

• A clear steady voice, each word carefully enunciated.

• A high, slightly girlish laugh.

• A damp shuttered bedroom.

• "My Darling Mother"

• Great warmth and a twinkle in the eye.

• An overwhelming sense of self-sufficiency.

• Home made jam and wild flowers in jam jars.

• A regular Sunday lift to church in Muthill from a neighbour.

• An old Bakelite radio.

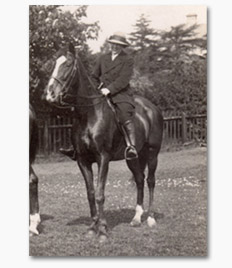

• An old hammer action 12-bore shotgun and a handful of cartridges that she used to shoot the odd pigeon and, once a year, a grouse unwise enough to feed on the half acre of heather behind the cottage.

• A relic of another era who was quite ready to engage with the times she lived in.

[When asked about his reference to Eleanor's childhood visits to Russia]:

I think I remember her talking about horse-drawn sleigh rides, and possibly also going to balls with them. As I write now I'm struck by the contrast between the very simple life she led as an elderly spinster in her cottage in Perthshire, and what I imagine to have been the glamour and excitement of those trips to her Russian cousins. I can hear her speaking about them now, she was very articulate and had very clear diction, but she also retained a certain girlish quality, and I remember she used to clap her hands in delight at things. I guess some of that would have come through in her description of those youthful trips to Russia. She brought back the spillikins and miniature (I think) patience cards and we played both with her as children in her little cottage.