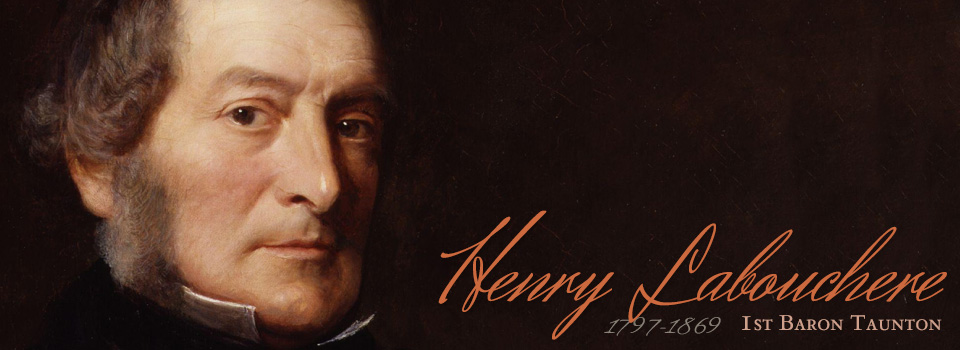

Henry Labouchere (1797 - 1869)

Henry was the first child and son of Peter Caesar Labouchere and Dorothy Elizabeth Baring.

("The London Journal" Vols. 5-6, 1847, page 104):

MR. LABOUCHERE.

The Right Honourable Henry Labouchere is a member of the present Cabinet, and the Secretary of State for Ireland. In previous Whig Administrations he has held high official situations. He was for two years one of the Lords of the Admiralty, viz., form 1832 till November 1834. In the spring of the year ensuing he held the Vice-Presidency of the Board of Trade, and Master of the Mint, which situations he filled till March, 1839, when he was appointed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies; and from 1839 till September 1841 he was at the head of the Board of Trade.

He first of all entered Parliament in 1826, when he sat for St. Michael's. At present he sits in the House of Commons as member for Taunton, which borough he has represented for the long period of seventeen years.

Mr. Labouchere, in the estimation of politicians, is still a young man, and considered one of the most rising statesmen of the day. He was born in 1797, at his father's seat at Hylands, in Essex, and has increased his political and family connections by his marriage in 1840 with one of the daughters of that wealthy and powerful baronet, Sir Thomas Baring, a brother of Lord Ashburton.

In being elected to take a great share in the government of Ireland, Mr. Labouchere has a very arduous duty to perform. In the endeavours to relieve the appalling distress of the Irish people, he has been the party towards the adopting, if he has not actually suggested, a series of bold and adventurous measures such as the wisdom and capacity of man scarcely ever dared before. The grievances of Ireland are not at present to be dealt with as matters of ambitious speculation, nor to be used as means of political aggrandizement. Mischief is to be corrected; it is to be traced to its most latent causes, and the remedies necessary for its cure are to be declared.

During the time that Mr. Labouchere has been Secretary for Ireland haggard famine and gaunt destruction have overspread the land, and the breath of pestilence has blasted the fair fields. In this state of things, while a destroying angel was passing over the bountiful earth, which was refusing to give food to the people, and the poor-houses were filled with paupers, the Labour Act was proposed to Parliament and carried, and in being administered gave partial relief to the wretched Irish. It is not unfair to imagine that a great many of the schemes suggested in it proceeded from the brain of the present Secretary for Ireland, considering the situation he holds, how remarkable he is for his statesmanlike proceedings, and what advantages he has derived from a long practical political experience.

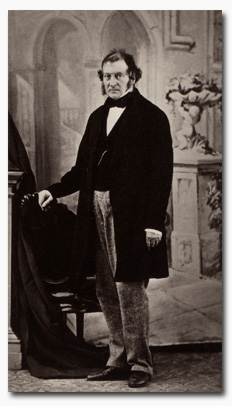

Mr. Labouchere's personal appearance is very prepossessing. He is handsome in figure and has a most pleasing countenance, though it is not remarkable for any striking intellectual peculiarity or superiority. This, Indeed, is the general characteristic of his efforts as a parliamentary speaker. Mr. Labouchere's speeches are more remarkable for the matter than the style, and even in this excellence, he hardly goes beyond mediocrity. Lucid arrangement and an earnestness of purpose in the inculcation of his arguments, are his leading qualities. He has the character of being a first-rate business man, which any one may see who reads the reports of the speeches he has been forced almost nightly to make in the House of Commons this session on subjects connected with Ireland. There is much mannerism in the style of the Right Honourable Gentleman. In addressing the House on the most trivial subject in answer to the most hap-hazard question he proceeds with as much pomposity of tone and manner, as if he was plunged into the depths of an official speech on a grand field night. At times, too, especially when the moral condition of Ireland forms the theme of his discourse, one would almost imagine he was listening to a popular preacher. His ordinary style of address savours very much of the pulpit school. But with all these defects, Mr. Labouchere is an able and effective speaker, and he must be found a valuable prop to his colleagues in the Government. With perhaps a slight dash of what some might call the "finical," in his manner, Mr. Labouchere is a most polished gentleman, and he is exceedingly popular in society.

The family of Mr. Labouchere was settled in France till the revocation of the edict of Nantes, when they emigrated to Holland, and there embarked in mercantile speculations, and acquired a considerable fortune. The father of Mr. Labouchere, Peter Caesar Labouchere, Esq., was the first of his family who settled in this county. He became a partner in the great mercantile house of Hope, and purchased the estates of Hylands, in Essex, and Over-Stowey, in Somersetshire; the latter of those estates now being to the subject of this memoir. Mr. Labouchere has only one brother, who is a banker in London.

("The Star" 15 Jul 1869, page 2):

DEATH OF LORD TAUNTON

We regret to announce the sudden death of Lord Taunton. He died between 2 and 3 o'clock on Tuesday afternoon, after an illness of only a few hours. On Tuesday afternoon, after an illness of only a few hours. On Tuesday last he spoke in the debate upon the Irish Church with even more than his accustomed impressiveness and authority; he spoke again shortly on Friday. Although he did not attend the House of Lords on Monday, he drove out in an open carriage, and it was only on Tuesday that the fatal symptoms appeared. Although never in the first rank of politics, Lord Taunton's career had been throughout one of high distinction. Born in 1798 he took a first-class in classics at Oxford in 1820, and was early initiated into official life. He was a Lord of the Admiralty from 1832 to 1834, Vice-President of the Board of Trade from 1835 to 1839, then for a short time Under Secretary of the Colonies, and then, returning to his former office, but with augmented rank, President of the Board of Trade from 1839 to 1841. He was, as he reminded the house in his last considerable speech, Chief Secretary for Ireland from July, 1846, to July, 1847, including, therefore a large portion of the famine period, and on leaving Ireland he resumed once more his old place at the Board of Trade, which he filled from 1847 until 1852, during which time he took a leading part in the repeal of the Navigation Laws. In 1855 he became Secretary of State for the Colonies, which office he held until 1858, and in the following year he was raised to the Peerage as Lord Taunton, a title which he assumed in compliment to the borough he had represented for nearly 30 years. Although he sat 10 years in the House of Lords, Lord Taunton will be best known as Mr. Labouchere, under which name the longer as well as the more active portion of his political life was spent, but in both Houses of Parliament he was generally and highly respected. Before entering parliament he travelled in the United States and in Canada with Lord Derby and the present Speaker of the House of Commons, and both by material interests and by sympathy he was largely connected with America. By his first wife, a daughter of Sir T. Baring, and sister of Mr. Thomas Baring, M.P., who also died suddenly in 1850, he had several daughters, one of whom is married to Captain Ellis, Equerry of the Prince of Wales. Lord Taunton subsequently married, in 1852, Lady Mary Howard, daughter of the sixth Earl of Carlisle, who survives him. Lord Taunton's last public employment was as Chairman of the Endowed Schools Commission; but in whatever capacity he appeared he increased the reputation he had early gained as a scholar, as a gentleman, and as a zealous and able servant of the public.

("Liverpool Daily Post" 15 Jul 1869, page 9):

HENRY LABOUCHERE, FIRST AND LAST LORD TAUNTON.

One of the strange contrasts which occur now and then in public as in private life has just taken place in the death of Lord Taunton. On Friday he addressed the Peers, and received unusual attention. On Monday Lord Stanhope spoke with great respect and interest of his speech, and expressed regret that he was absent through indisposition. Some one sitting near the Earl said "Lord Taunton has been here." Lord Stanhope replied, "He was here, but was not well enough to remain." This occurred some three nights ago, and now Lord Taunton's mortal part is prepared for its last home. He was only seventy-one, and he leaves behind him, apparently in full health, not a few peers from five to eighteen and twenty years his senior. Any one who saw him dashing about the purlieus of the House of Commons fifteen years ago, with his head stooping forward in the city manner, as of one bent on doing a quick stroke of business in the next lane, and who compared his wiry frame with the delicate physique of Lord Russell, several years his senior, would have thought it but little likely that in 1869 he would suddenly fade away from his old haunts, leaving Lord Russell stouter and better to all appearance than he was at 45. Such are some of the vagaries of health and debility, strength and physical failure. For a long time Lord Taunton looked languid and ailing. He always walked with a stick, and, though he did not absolutely lean upon it, seemed to find it of service. His voice quite lost its penetrating quality, without any accession of that careless sotto voce style to which, as well as to the bad acoustic characteristics of the House of Peers, the inaudibleness of many of their lordships is attributable.

Though the suddenness of Lord Taunton's death must have attracted some notice, in any case it is obvious that the interest awakened by it is mainly owing to the circumstance of his having so lately made the most impressive speech of his life. A man who had respectably held so many high offices could not but be held in high estimation in such a chamber as the House of Peers; but Henry Labouchere never was effective (except upon this one occasion) in any style but the easy, business vein which suited his character, and which was probably derived from his ban king and commercial progenitors. But on this one occasion he surprised probably himself, certainly the Peers, into real emotion. He began in his usual weak and ineffectual voice, and seemed unlikely to win the attention of the house, but he went on to speak of his own experience of the famine year -- of the indelible impression it had left on his mind -- of the acquaintance he had formed with the clergy of both religions in the ante-chamber of the Chief Secretary for Ireland (which office he held in that terrible year). As he spoke his spirit burned, and the flame was caught by those who heard him. It was a simple triumph, but a great one -- a triumph such as is occasionally made when a sudden revelation displays hitherto unexpected depths in a simple and generous nature.

Till last Friday the good man whose kindly sympathies were thus revealed had lived on the heights of the political life of his time without achieving any reputation but that for business ability, courtesy, and tact. He never originated or boldly illustrated any elevated idea, but he was always ready to harness himself to the chariot of progress; and a more trustworthy steed was never in the traces. From the beginning -- and his beginning as a member of Parliament was in 1826 -- he was a Whig. Two years before the Reform Bill he left the borough of St. Michael's, for which he had formerly sat, and was elected for Taunton. He was exactly the man a borough which once got him would never desire to part with. He was a Cardwell, without Mr. Cardwell's fishy coldness and apparently affected sentiment. Taunton never let Mr. Labouchere go till he took the peerage, which becomes extinct upon his decease.

He took office first at the Admiralty under Sir James Graham. The Administration of Lord Melbourne gave him till 1842 to improve his position, and he attained Cabinet Office as President of the Board of Trade. This fell to him again when his party re-commenced business with the Liberal profits of Sir Robert Peel's Corn-law repeal. The Whig Government -- for there were still Whigs even as late as 1848 -- had not much spirit, but they had enough to carry on Sir Robert Peel's free trade legislation. They proposed the repeal of the Navigation Laws, and in a very different way, but with satisfactory efficiency. Mr. Labouchere had a task somewhat resembling that which Mr. Gladstone afterwards performed for the French treaty. Mr. Labouchere was left out of the Aberdeen Ministry with his own consent, but Lord Palmerston restored him to his Board of Trade on acceding to the Premiership, and when Lord Palmerston resigned he was Colonial Secretary. The Willis's Rooms compact again left him out in the cold, and with his acceptance of a peerage his active career was at an end.

Of his last words we have already spoken. They will be frequently quoted in the coming concurrent endowment debates; and thus, in his latest moments, Lord Taunton won the right to be at least as well remembered as Henry Labouchere. As commoner he was a good and true servant of his country. As Peer, in his last speech he spoke remarkable words of genial wisdom, by which his country will surely in one way or other profit.

("London Daily News" 20 Jul 1869, page 3):

The mortal remains of the late Lord Taunton were removed from the family residence in Belgrave-square on Sunday for interment at Overstowey, near Bridgwater. The funeral takes place to-day.

("Birmingham Daily Gazette" 21 Jul 1869, page 4):

The funeral of the late Lord Taunton took place this (Tuesday) afternoon. The remains of the deceased nobleman were interred in the family vault in the parish church of Over Stowey, Bridgwater, near his lordship's mansion, Quantock Lodge. The funeral was strictly private.

("Morning Post" 22 Jul 1869, page 5):

The funeral of the lamented Lord Taunton took place on Tuesday, when his remains were deposited in Overstowey Church, a short distance from Quantock Lodge, the family seat near Bridgewater. The funeral procession left the mansion for the church shortly after twelve o'clock, the honoured remains of the deceased nobleman being taken in a hearse, and the mourners, clergy, and labourers following on foot. The body of the deceased lord was enclosed in several coffins, the outer one being covered with black velvet, ornamented with brass mountings. Beneath a baron's coronet was a brass plate with the simple inscription – "The Right Hon. Henry Labouchere, Lord Taunton, born 15th August, 1797; died 13th July, 1869."

The church was completely filled. Lady Taunton, Lady Elizabeth Grey, Hon. Mrs. E. Howard, and the three daughters of the late lord -- namely, the Hon. Mrs. Ellis and Hon. Misses Labouchere -- occupied a pew during the solemn service. The mourners were Captain Ellis (son-in-law of the late lord), Hon. Charles Howard, Admiral the Hon. Edward Howard, the Hon. and Rev. F. Grey, Mr. Thomas Baring, Lord Northbroke, Mr. H. Labouchere, Mr. H. Lascelles, Lord Ronald Leveson-Gower, Lord E. Cavendish, the Rev. J. Gallway, the Rev. J.W. Inwin, the Rev. J. West, the Rev. W. Gordon, Mr. Luttrell, Sir Alexander Hood, Mr. R. Buller, Mr. Liddon, Mr. King, Mr. Cornish, Mr. Woodley, Mr. Repster, &c. About 300 tenantry and labourers followed his lordship's honoured remains to the grave. The funeral service was impressively read by the Hon. and Rev. Frederick Grey, assisted by the Rev. W.E. Buller, vicar of Overstowey. The funeral was conducted by Mr. W. Radermacher, of Halkin-terrace, Belgrave-square. The Duke of Devonshire, the Duke of Argyll, and the Earl Granville were alone prevented attending the funeral by their parliamentary duties.

("The Statist: A Journal of Practical Finance and Trade" Vol. 30, 1892, page 532):

Lord Taunton (the Right Hon. Henry Labouchere), who died in 1869, aged 71 years, and whose widow died in September last, was noted, so it was written nearly 40 years ago, for his love of truth, and those who knew him best believed that no conceivable temptation would induce him to compromise his veracity. When the Eastern Counties Railway was cut through his estate, Hylands, near Chelmsford, he refused, so it was said, to accept some 18,000 or 20,000 pounds as compensation for the estimated damage to his property, because he did not himself believe that the railway had done any injury at all to his estate.

Numerous portraits of Lord Taunton are known to exist, as well as engravings and photographs. A striking portrait by William Tweedie is held at the London National Portrait Gallery. One posthumous portait by George Richmond is still in the collection of Port Eliot.