My Life: The Story of Mariamne Denissieff

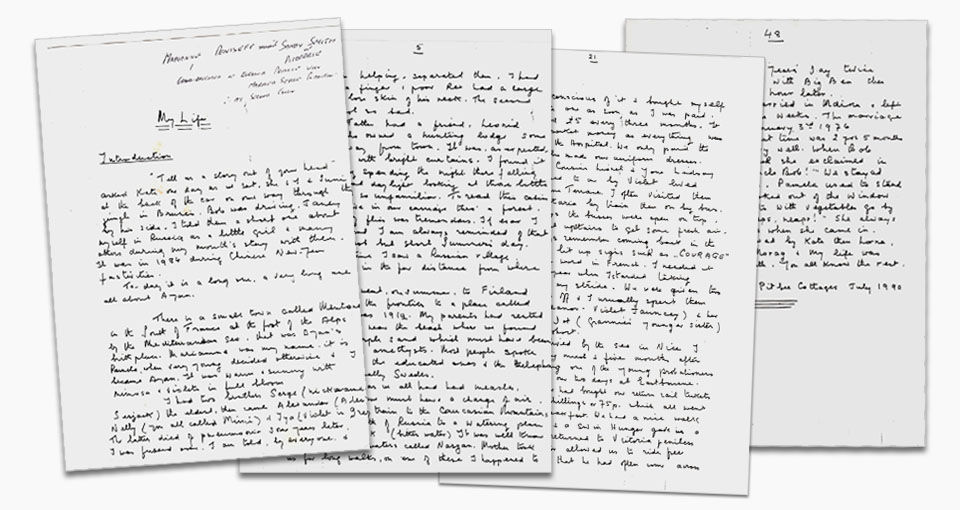

The following autobiography was written by Mariamne Smith (nee Denissieff) in 1990 as a gift for her grandchildren and published for them in a very small edition in 1991. She also presented the original unedited version as forty-eight handwritten pages to her cousin, Lord Charles Jauncey. He kept those pages with his own family notes about visits to Russia and France. It is the story from those pages that is presented here.

INTRODUCTION

"Tell us a story out of your head," asked Kate one day as we sat, she and I and Suni, at the back of the car on our way through the jungle in Brunei. Bob was driving, Janey by his side. I told them a short one about myself in Russia as a little girl and many others during my month's stay with them. It was in 1984 during Chinese New Year festivities.

Today it is a long one, a very long one, all about Ayan.

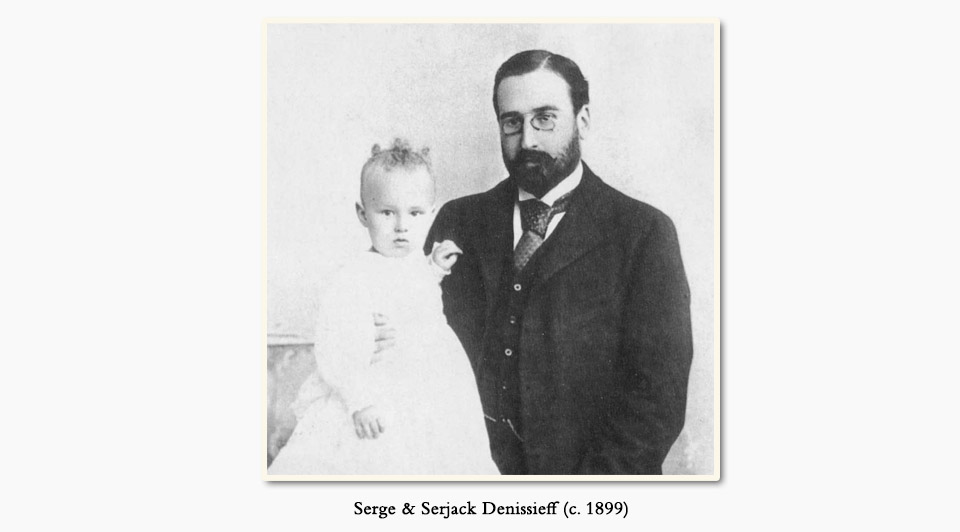

I had two brothers, Serge (nicknamed Serjack) the eldest, then came Alexander (Alec), Nelly (you all called Mimi) and Iya (Violet in Greek). The latter died of pneumonia some years later [1980]. I was fussed over, I am told, by everyone and called "Baby" for many years to come. I was looked after by my Nanny, Mrs. Hays, who was as large as she was kind, and my sister Mimi says that she can remember as if it was yesterday the day that she saw me for the first time.

I first came to Russia when I was three years old as I was supposed to have been delicate. We lived in Petrograd (the town of Peter, now Leningrad) in Lopoohinskaya Street, on one of the islands. The house was wooden and stood in its own grounds. It was built off the ground and we could crawl about underneath amongst the lagged central heating pipes. I can remember one occasion when I did this.

There was a short canal near the house which led to the river Neva that ran through the town between the islands. There was a lovely view across the river with a church near its banks. On the north side of the house was a large field where we skied in the winter. A drive ran along the nearer side where I learned to ride a bicycle, my father standing at one end waiting for me and my brother Alec setting me off. There was a stretch of land along the river which must have been on our land where barges were moored. One day Alec found a greyhound that had fallen into one. He retrieved it and brought it home. Father made enquiries and the owner took it away, not before it had managed to jump through a closed window.

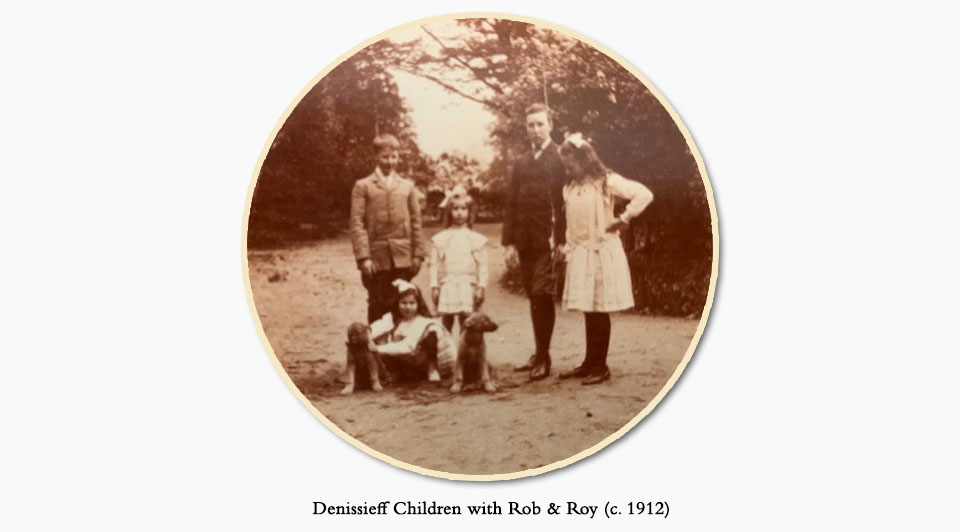

We had some grass in front of the house where our two Alsatians used to lie in the spring. Rob and Roy were brothers. As they lay enjoying the sun, crows came and picked out the underlying soft fur for their nests. The dogs never moved, enjoying the feeling.

A drive led from the house to the street which led to the larger thoroughfare with its electric trams that took you over the bridge to the centre of the town, passing the Admiralty building, then the Winter Palace Embankment (quai de la Cour) with its handsome private houses leading to the Palace itself. One of them was my grandfather's house, and when I was in Leningrad in 1961, I noticed it had scaffolding which meant it was being kept in good repair. We must come back to our house. There were two lilac bushes, one white and one purple, on each side of the steps leading to the front door. It may be for that reason that lilac is one of my favourite flowers. Not far from the house, on the way to the river, we kept rabbits. It was a mound surrounded by netting. On the drive before reaching the house was a wing which, during the First World War, was turned into a convalescent home by my mother for soldiers. She had passed the necessary exams to run it. She wore a veil and an apron like the nurses when she went over for her round. I went over several times but did not like to see the healing wounds being dressed which made me feel faint.

In those days, one had servants. We had seven. The butler, Ossip, had a daughter; she was about seven and Mimi taught her to read. She also taught me a poem "My First Tooth". I could recite it at the age of three. Then there was the footman, Philip, a younger man. The maid was Olga, and Mother had her own maid. I felt it was an honour when the latter helped me. I hardly saw the cook and kitchen maid as we were not allowed in the kitchen. Doonia, the laundry maid, I remember well. She got engaged and asked our mother to bless her before her wedding. There was also a yard man.

My mother was very fond of dogs. I have already mentioned the Alsation brothers, Rob and Roy. Rob was the elder of the two. He hurt his paw once and had a dressing on it. He came every evening and put his paw on my mother's lap to have it changed. Alec had a collie, not a Scottish sheep dog but the long nosed breed with very thick fur. He hated being brushed and had to be muzzled as he could easily have bitten you. His name was Don. Mother had a dachshund, Poopsik, which was devoted to her. Rex was Mimi's cocker spaniel given to her by her godmother for passing an exam. She was then 15 years old. I must not forget Boyka who lived in a kennel at the back of the house. He was the watch dog. His lead extended the whole length of the house in the open space at the back. It ran on a fixed wire. He had a large scar on one of his hind legs where he had been burnt as a puppy before we had him. Rob and Roy, who were fully grown when Rex came, no longer a puppy, could not stand him. They had to be kept apart. Twice, unfortunately, they met. Serjack and Alec, and I of course helping, separated them. I had a bite on a finger, poor Rex had a large tear on the loose skin of his neck. The second time was not so bad.

My father had a friend, Leonid Davidoff, who owned a hunting lodge some distance away from town. It was, as expected, a log cabin with bright curtains. I found it very exciting spending the night there, falling asleep in broad daylight looking at those little curtains, all so unfamiliar. To reach this cabin, we had to drive in our carriage through a forest. The buzzing of flies was tremendous. If ever I hear that sound, I am always reminded of that forest on a hot but short summer's day. It was the only time I saw a Russian village, unfortunately in the far distance from where we were.

Once we went, one summer, to Finland, not far across the frontier to a place called Terioki. It was 1912. My parents had rented a villa. It was near the beach where we found patches of purple sand which must have been crushed and worn amethysts. Most people spoke Swedish, that is the educated ones, and the telephone staff were actually Swedes.

In 1915, as we all had had measles, Mother decided we must have a change of air, so we set off by train to the Caucasian Mountains right in the south of Russia to a watering place called Kislovodsk (bitter water). It was well known for its mineral waters called Narzan. Mother took us for long walks, and on one of these I happened to look round at a lady passing by. Mother told me it was rude to stare at people, to which I answered: "I was not looking at the lady, I was looking at her hat." We stayed at a hotel and every evening we hung our navy serge skirts outside our bedroom door to be brushed. One morning, I found a tiny bunch of flowers pinned on to my skirt. It was from a little boy, aged 9, whom I had met the previous day while we were playing outside.

Kislovodsk is situated on the northern lower slopes of the Caucasian range which is between the Caspian and the Black Seas. It is here, on these slopes, that Mimi went riding with an instructor. I, as usual, was not going to just watch and managed to get Mother to allow me to ride Mimi's horse for a little while. It did not take the horse long to realise that I knew very little about being in control and it decided to carry me at a gallop in the direction of the stables. The instructor came to my rescue.

As I have said above, it was 1915, in the second year of the First World War. I remember the taking of the town of Erzerum by the Russian forces from the Turks, the town being in the Turkish province of Armenia.

After two or three weeks, we returned home. The journey by train took two days and one night. We passed Moscow without stopping.

We had a coachman, a horse drawn sledge and several vehicles, open and closed ones. As we travelled a lot, we did not own horses but hired two when at home. They were call Little Basil and Little Breeze (Vaska and Veterok). The carriage came to the door every morning to take Father to work. As the coachman waited, Mimi used to climb on to the horse for fun. One day, Father and Mother were going to town; they did not take me but I was determined to go, so as they set off, I climbed on to the springs at the back and when we were well on our way, I called out and was put between them. I don't remember being scolded. On one occasion in the winter, my godmother took me for a run in her horse drawn sledge to a point on the Gulf of Finland which was a popular spot to drive to watch the sun set. I still remember the smell of the large brown bear skin which covered our legs.

It was 1916 when we moved from this house to a flat in one of the main streets. Once again, I don't know the reason. We had to give away the dogs, except Poopsik, my mother's dachshund. My two brothers attended the Imperial Lycee which was opposite the flat. That Easter, we went to the midnight service in the chapel of the Lycee. The knowledge that the choir was made up of blind singers made an impression on me. In the Russian Orthodox Church choir, there are no boys' voices, only men's and women's.

Mother died in the spring of 1916 [sic]. She was 46 [sic]. She died of pneumonia. That summer, Father got us to go to Finland with our French governess, Mlle Labarre. We had bought, some months earlier, a plot of land on the river Vuoksa. The wooden house which was being built unfortunately burned down through the carelessness of a workman with his cigarette. We had rooms above a grocer's shop and bathed a lot. It was here that Alec taught me to swim.

In the autumn of that year 1917, the revolution was brewing and troubles had started with mobs fighting the police in the streets. Father very wisely contacted Granny and Grandfather in Nice and arranged for us girls to leave Leningrad with Mlle Labarre. As Serjack was starting university and Alec was finishing his secondary education, Father did not think they should leave. He thought the revolution would only last a few months, and we would then return home. We therefore left by train for Archangel and were met by one of our Plaoutine cousins, Michael. He died soon after [1920], shot by the bolsheviks.

Father had managed to get us berths on a British cargo boat sailing for Montrose with a cargo of capoc.

Before carrying on, I would like to say a few words about Father. He was a mining engineer on the staff of the Mint. He coached Mimi for maths. She never liked them and was never good at them. He was too old and my brothers too young to take part in the war at that time. He was also a sportsman in his younger days, and won prizes in cycle races, amongst them a gold pendant representing a bicycle wheel of gold with a diamond in the centre that he eventually gave to Mimi. He also played tennis and taught her. During the revolution, he earned his living by coaching students in maths. Once in power, the bolsheviks were merciless and shot not only the Imperial family, but thousands of people they thought a menace to their party. My Uncle Misha and Aunt Lillie were victims. As I said, Father was on the staff at the Mint and was put on to the list to be shot. The workmen, through their petition, saved his life.

Archangel was a sleepy town with hardly any traffic. There were duckboards replacing pavements to keep you out of the mud. Very few people about. We actually sailed the day the bolshevicks came into power. There was a large passenger ship in the harbour about to sail and years later, we found out the Mimi's future husband, Kyril Armfelt (you know as Papy) and his mother were on board, heading for Poland.

The whole country was suffering from shortages of food, therefore it was a pleasant surprise to have unrationed white bread and sugar on the dining-room table.

The Captain was a pleasant man. He used to take me on his knee for a chat as I reminded him of his daughter. One day he asked me if I had been lonely. I said "no" as I thought that lonely meant alone.

We headed through the White Sea to the Norwegian Fjords. At night we were told to wear our life jackets as the sea had been mined. We sailed in a convoy and were told that one of the ships had struck a mine. It never entered my mind to be frightened; it felt like an adventure. I remember the fjords well. I found them magnificent. We put into harbour once in Aalsund. The little grey houses perched down a slope to the water's edge looked like a toy village. Passing the Shetland Isles, I looked out for Shetland ponies but never saw any. We landed in Montrose on a Sunday morning. Walking down the street to the railway section, I noticed a group of children heading somewhere, and I was told they were going to Sunday School. This horrified me. "What a country, they even go to school on a Sunday," I thought to myself.

Granny must have contacted one of her cousins, Evelyn Kennedy (Aunt Vivi), who had reserved sleepers for London for us. Mlle Labarre was a little annoyed as she was bringing a sum of money to Granny but had to pay for the tickets. By the way, she refused to bring out Mother's jewellery as she did not want the responsibility of it.

In London, we stayed with Aunt Vivi in Cranley Gardens. Our rooms were at the top of the House with barred windows. They had been nurseries.

The dining room table was beautifully polished but had no cloth on it; that struck me as strange. The meals seemed so luscious. During our stay in London, we experienced an unexpected event. The police were looking for a Russian governess (a spy) with two boys who had left Russia at the same time as us. We had to go to the police and be interrogated; they soon discovered their mistake.

We stayed ten days with Aunt Vivi, then carried on to France via Southampton and Le Havre. The journey was uneventful, although it was war time. We never actually reached Nice railway station by train as the locomotive had broken down near the River Var some fifteen miles away. We all clambered down to the road where buses had come to pick us up. We got out in the rue de France, named that way as the County of Nice was Italian and became French in 1860 – it was the way that led to France. The street that took us to the foot of the steep Avenue St Laurent came off it. Mlle Labarre must have been quite exhausted when we reached Chateau St Laurent and my grandparents' flat. Granny seemed quite surprised to see us arrive earlier than expected.

We were a little bewildered by our surroundings but settled down quickly. Grandfather, a sweet and gentle person, greeted us warmly. A couple of weeks later, we bacame ill with mumps. Mlle Labarre was not well, I think liver trouble, and soon left for her home town of Bordeaux. Mme Pacotte, a doctor's widow with a daughter in boarding school, appeared to replace her and I started boring lessons with her on my own. When her daughter Camille was on holiday, she lived in her flat down in the Valley of la Madeleine; during the term she slept with us. The days she slept away I always hoped that something would prevent her coming the following morning. I anxiously looked out from the balcony to see if she would appear, coming up the hill.

Grandfather had two nice ladies who came to read the papers to him. One was Russian who came from Kieff. Her name was Ovsiannaya. We nicknamed her Mrs Oats, as ovis is oats in Russian, eventually she became Mme O. who gave me Russian lessons. Mrs Greenhill, who came on alternate days, read the English papers; she came from Devon and lived with a married son across the Valley. We could see their flat window from our rooms. Grandfather was deaf and we spoke to him through a mouthpiece; his sight was also very bad.

After three years, Granny at last heard of a school for "nice" girls I had longed for. So at the age of fifteen, I went to school for the first time.

Chateau St Laurent was an attractive three storey building standing in its own grounds. It belonged to two English spinster sisters, the Misses Gurney. They inherited it from their father, Dr [Henry Cecil] Gurney, who had acquired it with a view to turning it into a nursing home at the turn of the century. The sound of the trains running at the foot of the grounds, the P.L.M. Paris-Lyon-Mediterranee, proved too noisy for the comfort of the patients, so the idea was given up.

It was situated on a slope on the edge of the west end of the town. Rich vegetation surrounded the villas there. From our balcony we could see the sea due south over the roofs below us. When bathing, we swam out until we could see the house. We saw it from Galena in 1967 when sailing to Malta.

The building had a ground floor and three floors above. Miss Gurney and her sister lived in a maisonette at the east end of it. The west end was occupied by a Canadian with his Swiss wife and two little girls. Their flat was also a maisonette. In between them, on the first floor, lived Miss Walsh with an Italian companion we nicknamed Rayon X (x-ray) as she was very inquisitive. Granny and Grandfather had the second floor which ran the whole length of the building. On the photograph from right to left: Granny's bedroom, the diningroom, the drawing-room, and lastly Grandfather's bedroom. On the top floor lived a French couple - survivors of the Titanic disaster.

Granny and Grandfather's was beautifully situated with the sun shining in the whole day. In the east end was the kitchen, the cook's bedroom, the tradesmen's entrance at the north end of the kitchen, then east the bathroom, south Granny's bedroom, the dining-room, the drawing-room. Grandfather's bedroom had a window looking due west and a French window leading to the balcony. West was my bedroom, Mimi's bedroom and the classroom. On the northern side was a spare bedroom which was used by Mme Pacotte, the governess I mentioned earlier, when her daughter was at boarding school. Then came the front door leading to a white marble staircase. Then Amelie's bedroom looking out on to the road. It led up and turning right to follow the top edge of the railway line. In between all these rooms was a long passage joining them.

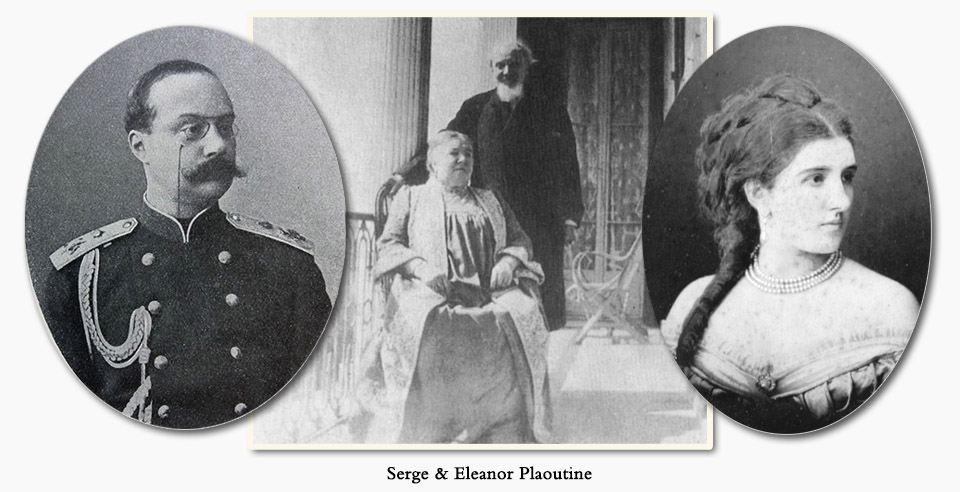

My grandparents rented this flat, which was furnished by Miss Gurney. My grandfather had been a very wealthy man in Russia and owned several estates. He said Russia was a young country with a future, so he never took any money out when he left St Petersburg for Nice in 1914. He only owned a couple of pictures, some Russian coins and a few French bronzes. He sold everything one by one when money stopped coming from his estates from the day the bolsheviks came to power.

The flat was carpeted throughout. The carpets were taken up every spring, beaten on the terrace below and stored by a firm until autumn. The floors were tiled and easy to keep clean during the dusty summer months. If a mattress (they were all hair mattresses) needed redoing, a man would come and carry it down to the terrace and card it there. In those days, glaziers with large panes of glass carried on their backs would walk the streets calling out their wares.

The Miss Gurney I talk about was the elder of the two sisters; Amy was the younger. She was a quiet little person who never took decisions. There was also an Italian person, Miss Gina, who looked after the pigeons in a large aviary and fed them on maize. We liked her but nicknamed her Rusty Tooth as she had brown stains on her teeth.

There was also a gardener who tended the flower beds. A lot of watering had to be done in the summer months. Miss Gurney did not approve of us running about on the paths and perhaps stepping onto a bed by mistake. She used to get very annoyed and called us "barbarians".

The grounds of Château St Laurent were very lovely, all on a slight slope, with gravelled paths amongst the rose beds, all bordered with pale grey velvety plants where hid slow worms pretending to be snakes. Looking into one of these large roses, you would invariably find a large and beautiful greeny-gold scarab. The oleander trees could be seen from the house along a path.

There was also an avenue of Seville oranges (bitter). Cork oaks filled the remaining space down to the railway line. Here there was a cutting through which the sounds of the bells of the Russian Cathedral could be heard rich and deep. The building was founded in 1914, just before the First World War. The funds were raised by the Russian colony. It was beautiful, and had an outstanding choir. From the age of 15 until I left for London, I hardly missed a service on Sundays and feast days. I had to ask Granny the permission to go. If it rained, she would not allow me, so I waited until it stopped for a few moments to ask. I took the small country road above us going east high up parallel to the railway. It had a few nice villas on it. It was known as Les Collinettes.

Up to then we had hardly made any friends, as Granny was very strict about whom we should meet. Thanks to Mme O., we got to know two French sisters, Paule-Andrée and Rolande Schmidt, whose father owned several hotels in Nice. Mme O. gave them Russian lessons. We saw them often and joined them in their carriage for the battle of flowers during carnival time. Carnavale (Italian) means farewell to meat - the week before Easter Lent. As I think I have already mentioned, Grandfather, up to the revolution of 1918 [sic], had been one of the wealthiest land owners in the country. His younger son, Michael (Uncle Misha), managed the estates and money flowed in regularly. When the troubles started, the supply ended abruptly and we would have been penniless without the very kind gesture of one of Granny's cousins, the Hon. Ronald Lindsay, who was British Ambassador in Washington. Thanks to him, we carried on a normal life. The only difference was that the maid was replaced by a daily cleaner. The cook and Granny's maid, Amélie, remained.

My grandparents up to then had spent the hot summer months in Royat - a watering place in the Auvergne. They had to give this up and we all went up into the mountains and enjoyed our holidays without governesses, meeting our friends, the Schmidt girls. We had a rented villa in St. Marin-Vésubie.

During the summer of 1924, Granny was not well enough to leave, so she sat most of the day in the middle of her bedroom with the windows and doors wide open. She died that year after a short illness, aged 82.

Granny's maid, Amélie, stayed on and looked after Grandfather. I heard her every morning pulling his curtains and bringing his breakfast, saying loudly to him: "Bonjour, mon Général, il fait beau ce matin." He outlived Granny by one year and died of loneliness and old age. He was 91. They had been married for 56 years. By then I had left for London and a very new life.

About 1920, the Russian revolution continuing, thousands of Russians left the best way they could to the west, away from the hunger and death. Many left on foot carrying their young children. Among the people who left was a timber merchant from Archangel, Valneff, with his wife and daughter of Mimi's age. He managed to take away his capital. He bought Chateau St Laurent. Miss Gurney had built herself a villa nearby as she felt it was time to retire. A second merchant, also from Archangel, bought a very nice villa a little higher up the hill. His wife and daughter gave parties for us young ones which we enjoyed. Having left school, I started earning some pocket money. My first job was teaching French to a six year old Turkish girl. We sat on the beach with a picture book and I pointed out what we saw in French. We used to go back to the house for tea prepared by the Turkish maid. I learned one word in Turkish - "Bilmurun" - which means "I don't understand". The little girl's father, like most educated Turks, had studied in Germany.

It was in the spring of 1924 that my appendix started to grumble and our doctor Walter (a Russian Jew) decided it should be removed. The Greenhills (mentioned earlier) had remained friends of ours all these years and they decided French nursing was not good. They managed to get me admitted to the Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital on a slight promontory on the way to Nice harbour, as I was the granddaughter of a Scottish person.

I was duly admitted and the operation was performed by a French surgeon. The matron was Scottish, a Miss Adam, young and pleasant. When I told her I didn't know what sort of work I would like to do for my living, she suggested nursing. I must say the nurses were very nice; they would come and eat my chocolates and tell me about their site-seeing. The impression I got was of a wonderful profession: you ate chocolates and saw the world. Miss Adam mentioned to me that King's College Hospital matron was on holiday in Menton. She could arrange a meeting. And so a few days later, I set off by train into the unknown. Miss Wilcox (sister of the film producer) was pretty imposing but pleasant. She decided that I looked older than my age - 19 instead of 18 - which was the age for starting training. She sent me the application forms as soon as she got back to the UK. I had to produce medical and dental certificates from British professionals. That was easy as in those days there was a very large British colony living along the Riviera with their own Anglican church in Cannes, Nice and Menton. So, in October 1925, with all my friends offering me flowers, my train moved off from Nice. I left these friends and the sunshine, travelling alone for the first time in my life. On my way through France, I spent a night in Paris with my widowed Aunt Maya (my elder Uncle's wife) who had managed to leave Russia in 1920 through the Kingdom of Serbia (now Yugoslavia). To live in the UK, I had to have a guardian, as I was still a minor. Violet Jauncey accepted the responsibility. She met me at Victoria Station, London, and took me to her club in Hill Street and gave me my uniform that had been sent to her. I was a bit taken aback with the thick woollen stockings. They proved far more satisfactory for hot tired feet than other types that other nurses wore. We set off to King's College Hospital, Denmark Hill, SE5.

There were eighteen of us starting in this set. I spoke with a fairly pronounced accent; I had not yet mastered the English ‘R'. I was very soon nicknamed "the foreign body" (something in your eye is a foreign body). I was the first foreigner to train there. I had a Norwegian passport, that is, a Nansen one. He was a Norwegian philanthropist who managed to get displaced people an identity document. (We had left Russia and our Imperial passports were no longer valid.) Being a foreigner, I had to report at Vine Street Police Station at regular intervals. One year, I forgot and a policeman stood at the entrance of the ward I was working in. I apologised and all was well.

Everything seemed strange compared to my life in Nice. The English girls with their ways, their chat. Boots for a chemist seemed a strange name. They wore modern underclothing. Amélie, who made most of our clothes, even winter coats, had made me a very old fashioned set. I was very conscious of it and bought myself an up to date one as soon as I was paid.

We earned £5 every three months. It was really pocket money as everything was provided by the hospital. We only paid the dressmaker who made our uniform dresses. My Granny's cousins, Lionel and Yone Lindsay, were introduced to me by Violet; they lived in Westbourne Terrace. I often visited them, going to Victoria by train and then on by bus. In these days, the buses were open on top. We always sat upstairs to get some fresh air. I shall always remember coming back in the dark and seeing lit up signs such as ‘COURAGE' (Ale), the same word in French. I needed it for about a year when I started taking everything in my stride. We were given two days a month off and I usually spent them with Va (Eleanor-Violet Jauncey) and her mother, Aunt Dot (Granny's younger sister); she was very short.

Having lived by the sea in Nice, I missed it very much and five months after starting training, one of the young probationers and myself spent our two days off at Eastbourne. By the time we had bought our return rail tickets I had only 15 shillings (or 75p), which all went on our bed and breakfast. We had a nice walk on Beachyhead and a swim. Hunger gave us a headache. We returned to Victoria penniless. The tram conductor allowed us to ride free to King's. He said that he had often come across nurses going back unable to pay the fare. Our training lasted 3 ½ years, 1925-29. The nurses were often asked to stay on a few months at the end of their training. During our training, we had to work about six weeks in every ward so as to gain experience in nursing all the various cases before sitting the final exam for the Certificate of State Registered Nurse. Midwifery was quite separate. It took six months. I did it with two friends, Joanie and another, at Chiswick and Ealing Maternity Hospital outside London. My very first ward was ‘Ear, Nose and Throat'. It made all the difference if the sister of the ward was pleasant; this one was. I spent my time with my eye on the ward clock so as not to fall behing in my work. After six weeks trial, the sister decided whether you were suitable as a nurse and you decided whether you wanted to spend the next three years training to become a qualified nurse. As I said before, we were eighteen in our set, all starting the same day.

After three years only six finished the course. One preferred marriage, one got flat feet, one did not like the work, one gave up through ill health, etc. Our first six weeks were spent in ‘Garden House', a small building in the Hospital grounds. There we learned mostly practical activities, such as cleaning out a room, lighting a fire, making a bed, washing patients in bed (known as a blanket bath). A dummy lay in bed during the making of it. We learned the name of surgical instruments, bathing a celluloid doll. After these six weeks we entered the ward we had been assigned to. We had a bedroom in the Nurses' Home and we were allowed no more than 15 articles on the table and on the chest of drawers. We were awakened every morning at 5.45am by a very loud elecric bell outside in the corridor. We got so used to it that I found myself sleeping on and dreaming that I was dressing. If late for roll call, we had to go and apologise to the Home Sister, that morning ‘Lizzie'. Going to Assistant Matron was always very daunting, but we were young and full of life and not in a ward, so a lot of giggling and whispering took place. We queued for theatre tickets which were given free by theatres in town, that is, if we were free that evening. The Assistant Matron was nicknamed ‘Fluffy', a high spirited joke; her appearance was far from that. One of her eyelids was slightly contracted through an accident involving carbolic acid, which gave her a very severe expression. I well remember an incident in which Joan Evans (Joanie) had to go and see Fluffy. We in the queue stood outside and watched. Joanie was standing with her arms tight against her sides. "Lift up your arms, Nurse," said Fluffy, which Joanie did, revealing a large tear in her dress. You can imagine the suppressed mirth amongst the waiting nurses. Poor Joanie had to go and change her dress.

After breakfast we went to our respective wards, starting work at 7am. At 11am, we had 20 minutes for coffee, bread and dripping, which I enjoyed, and then we changed our aprons. The day nurses' work stopped at 9pm, unless they were off from 6pm to 10pm. The night nurses and probationers started then. The off duty was four hours, 7am to 11am, 2pm to 6pm, or 6pm to 10pm. If off at 7am, breakfast was at 9am.

When off duty we were obliged to go out at least twice a week as "a duty towards ourselves". We sat on top of buses for fresh air. There was a timetable sheet in the Nurses' Home entrance we had to fill in. Sometimes we were not very honest and filled in going out time when we stayed in and went up for a sleep!

In our set I made friends with Joanie and Marion Denny. We often went out in small groups. Being young and bubbling over with life, the moment we left the Hospital building it all came out. We got on the tram taking us into town, Joanie sitting with her mouth wide open like a half-wit, we pretending not to know her. When on night duty we went out in the morning. One time I bought a dozen Bath buns thinking of sharing them with friends. By the time I got back, I found they had all gone to bed and, hungry as I always was, I ate them all myself.

We were allowed three weeks holiday a year. Every year I spent my holiday with Mimi and Papy.

I had a little money in the bank from the sale of Granny's things. The return trip to Nice via Newhaven-Dieppe was £11. I used to get my ticket well in advance, which made me feel well on my way to the sunshine. I couldn't afford a sleeper so sat up all night in second class. By the morning, the train was well south and I got more and more excited.

At my first visit, I saw Helene for the first time. She was 8 months old -- a lovely fair haired bouncy baby. Joanie came two years running from Hospital then after we had trained. It was great fun, but horrid packing and coming back to earn more money for the next trip.

One of the most unpleasant moments in those days was when I woke up in the morning after my holiday still thinking I was away. Then I realised I was back and had been appointed to the women's surgical ward which had a horrid ward sister. I managed to keep in her good books. One day I had to let her know that the Chaplain had come and I said to her, "Sister, the vicar would like to speak to you". She corrected me and said: "Not vicar, Nurse, but clergyman or priest."

I was called to Sister Matron's office twice during my training, once to interpret for a Russian private patient. The second time she showed me a letter and asked me to translate it. I had to tell her it was in Hebrew!

Once a year we sat exams and the finals came and all was well. I got first class in surgery and second in medicine. In cookery I burned the toast but that did not affect the result.

I must explain that years back, when King's was still in the Strand, it was a convent hospital and that is why the word ‘Sister' was used: Sister Matron, Sister Tutor, Sister Elsie, etc. When off duty and in the building, we had to wear hats. We were not allowed to speak to male students and at Christmas with a lot of coming and going in the corridors, the Home Sister stood in a strategic position to see that no conversation took place.

There was snobbishness as well: dental nurses, massage staff, physiotherapists were far below us nurses! When I first went to the Ear, Nose and Throat ward, I happened to use the word ‘maid'. She heard me and snapped back saying "Phyllis to you".

The ward I liked the least was the children's ward. I was there on night duty as a probationer. I was so sorry to see all those sick little faces.

We were all very afraid of the night sister. She was tall, had flat feet and had her hair in a bun. On night duty in one of the wards, I had taken a lot of trouble to get a patient to sleep. Night Sister came along and when she heard him breathing a little heavily, she turned his head over and woke him up! Another time there was a black patient in the ward and Night Sister said to me: "If this patient goes blue let me know." That was not easy to see in a darkened ward.

In spite of her looks she was really quite nice. She often took us night nurses sightseeing in town in the mornings.

In 1929 I became a State Registered Nurse and stayed on for three weeks after the finals. When I took my leave of King's I was given £9 and felt very wealthy. I went off to the South of France for a lovely holiday. Joanie came with me. She and I and another nurse of our set, Laverack, decided to train as midwives to complete our careers. We joined the staff of Chiswick and Ealing Maternity Hospital. It was a small cottage hospital in its own grounds. The work was not hard, nothing like the training in a large maternity hospital in London. There was a nice lawn where we held croquet competitions. During our training we had to deliver three babies in the district in their own homes. The midwife who accompanied us was a rough looking woman. As she scrubbed her hands before the delivery she always had a water mark on the rest of her arm; where the scrubbing stopped was pale grey. One time when she and I were called out in the middle of the night, we asked a policeman the way to the address we had been given. He just exclaimed, "It is my wife!" and we followed him at great speed. The policemen's married flats were very nice.

Some cases lived in slums, two or three or more children on one bed with no sheets or pillow cases. They had been given the necessary linen, but had pawned everything. When I returned to see the baby the following day, the little white dress was grey where dirty hands had lifted the baby.

Once my midwifery course was over (6 months), I applied for private work and joined the Mrs Coward's Private Nurses Agency, George Square, Pimlico, where I worked from 1930 to 1937. Mrs Coward was Noel Coward's aunt by marriage and was very proud of him. I decided on that type of nursing as the pay was better: £4 per week, £5 for doctors' families. I could also stop when I wanted to for as long as I liked, usually until the savings ran out! I was just taken off the books until I returned. There was always plenty of work and I was hardly ever waiting for a call. In between cases, I lived out at Hampton with Joanie's mother, Mrs Mason. Joanie by then had joined the Overseas Nursing Organisation and was in the Colony of Nigeria where she met her future husband. I was unable to do so as I had not yet got a British passport.

Most of my private patients lived in the home counties or in London. Very few of them were unpleasant. I used to take the train to wherever the case was and was picked up by a chauffeur driven car. I used to try and guess what the family I was going to was like. Sometimes it was a small Ford and obviously a handyman at the wheel; sometimes a large smart car with a smart chauffeur.

On one occasion my cousin, Yone Lindsay, asked me to stay with her mother, Aunt Vivi Kennedy (with whom we stayed in London), while her attendant was on holiday. It was at Burnthouse-Cuckfield near Haywards Heath, Sussex. It was a leisurely time but oh so lonely and boring. The only person I spoke to was the butler. He lent me his gramophone and a record ‘Lonely awakes my heart' out of Samson and Dahlila [sic], which I played again and again. Aunt Vivi liked rabbit pate so I went out and shot her a rabbit now and again in the glade nearby. She was very sweet and offered me the choice of an evening dress or driving lessons. I chose the latter and had six lessons with a garage owner. For experience in traffic we went to Brighton. That was in the 1930s. I never touched a car again until 1951, when in Knockbreck, Tain, we had an old Austin. When the doors started falling off we got the Allard. I had preserved my driving licence and only had to send it off to be renewed. It came back by return of post, but to drive I had to start again from scratch.

Aunt Vivi's son Leo was Assistant Foreign Editor of The Times newspaper. He came to visit his mother every weekend. He taught me to shoot with a rifle. We aimed at an orchard near the house. One day the neighbour rang to ask us to aim some other way as the bullets were flying around his wife's ears!

In 1932, after a short time in Nice, the whole family including Papy's mother, Countess Sophia Armfelt, and myself set off for Grenoble where they had found rooms for their summer holidays. I carried on to Berne to stay with Granny's cousin, Countess Ada Sermoneta (family name Caetani – Aunt Vivi's sister) who was there to get away from the great heat of a Roman summer. As with Aunt Vivi, her attendant had gone on holiday and I replaced her. Aunt Ada was a grand old lady in her eighties, completely independent in her ways. We were staying in Hotel Bellevue. We had a suite each (bedroom and sitting-room) and a balcony overlooking the river Aar and the Jungfrau in the distance. I used to go down and bathe, walking upstream for about ½ mile, throw myself in and let the current bring me back down.

I got to know a young secretary and his wife. He was at the British Embassy and we often bathed together. I also got to know an American working at the US embassy. He was separated from his wife who lived in America. As he was going on a trip to Venice, he asked me to accompany him. As I did not want to go alone with him, I got my new English friend to join us. Aunt Ada was very sweet about letting me go and said: "It only goes to show how nice you are."

The car was a two seater with an open boot at the back, known as a ‘dickie'. My friend sat there in the fresh air; she was expecting her first baby and not feeling too great. It was a very nice holiday; we went and returned via the Brenner Pass.

It was during Mussolini's fascist time. As we stopped at one stage to have a look at the engine, two ‘black shirt' young officers stopped and offered us their help. When we started up they said they would follow us in case we needed help. Their political party was out to become popular.

As I have said, Aunt Ada was a grand old lady. She had married into one of the oldest Roman families. She had six sons and one daughter. I met one of the sons. When he was a young man he had had a long illness and during his convalescence, he started to study sculpture and became a good sculptor. I saw the Palazzo Caetani, the name engraved on the large columns of the entrance, when Colette Leslie and I visited Rome years later. It was a sombre entrance in a narrow street, but I expect magnificent inside. The palace and the estate in the country had passed into a different branch of the family as Aunt Ada's only grandson was killed when Italy was at war with Albania in the 1930s.

The Viennese Choir Boys were in Berne staying in our hotel. Aunt Ada asked the choirmaster if the boys could sing for her, which they did.

On my way to and from Nice, I used to stop overnight in Paris with Aunt Maya, the widow of Uncle Koli (Nicolas), my mother's elder brother. She spoke of "Googa" – George. It was her youngest son who was divorced and working as a surveyor to the French Government ‘Ponts et Chaussees (Bridges and Roads). He had two children who were being cared for by an elderly Russian couple in the country in Burgundy (Central France). Aunt Maya suggested that I should go and see him during my holidays between private nursing and Nice. He was in the port of Nemours, Algeria, quite close to the Moroccan frontier. In the autumn of 1936, I set out to visit him. Nemours was a busy little harbour, an outlet for the minerals of Morocco. George was very friendly and we got on well. We corresponded and when I returned, we became engaged. Waiting for formalities to be completed, we did some sightseeing. We visited Fez, the largest town in Morocco, where he gave me the two brass peacocks, which were actually containers for scent, and my engagement ring. We were married in February 1937 by a Russian priest. I soon succumbed to a tummy infection. The doctor said I was lucky that it turned out to be a fairly mild one. The children, Michael (Misha) and Mary (Masha) were by then 10 and 7 respectively. With their education in mind, George managed to be transferred to Philippeville, a fairly important harbour between Algier and Bone, the latter not far from Tunisia. For interest sake, Oranie ( the most westerly), Algeria and Tunisia were part of France. We found a very nice flat on the outskirts of the town. It had two storeys. We were on the ground floor with a terrace and a thick wild vine that sheltered us from the hot summer sun, also a small plot of land where later I grew tomatoes and aubergines which flowered and developed in no time.

Once organised, we left for Paris to collect the children who were staying with their Granny (Aunt Maya) awaiting our arrival. She lived at Sceaux, a suburb of Paris. It was during the International Exhibition. We went to visit it. What stuck in my mind was the USSR pavilion where the European Russia was laid out in green enamel with the rivers and towns made of precious stones.

When in France, Misha went to the local school, so spoke French as well as Russian. Once in Philippeville and ready for school, Masha had to learn French, which she did very quickly. As she was born in Morocco, she told everyone at school that she was a Moroccan.

On 3 September 1939, Great Britain and France declared war on Germany who had invaded Poland. George was mobilised and joined the Engineers and left for Medea, a small village in the Middle Atlas, south of Algiers. We joined him and lived in a nice villa. There were occasional air-raids by the Italians over Algiers harbour. We were told that when they first started, the people used to stand on their balconies and watch the bombs fall and explode!

The Germans walked through Holland, Belgium and France, eventually occupying the whole of France. Until then I was able to send Papy, Mimi and Helene dried bread and dried dates as they were short of food. Helene was dancing in Marseilles Opera House.

When the British and American forces landed on the beaches of Algeria, that is when the Germans and Italians started their air-raids. Once Germany occupied the whole of France, the French out of the war, George was demobilised and we returned to Philippeville. I was by then expecting my little girl – Helene. She was born on 24 Aug 1940, the same day as Pamela, my granddaughter, thirty four years later.

The months passed; we had dug a shelter in the front of the house as we were getting raids from German and Italian planes. A few days after Christmas 1942 the sirens went off, warning the civilians of approaching enemy planes. Misha left the house for the shelter. Aunt Maya was just leaving her seat, George was standing by my side and I was about to stand up with little Helene when there was a crash, the lights went out and part of the upper floor came crashing down. George, Helene and Aunt Maya were killed outright. Masha, about 10 feet away from me, was pinned down by her leg. I had a beam right across my shoulders, so was doubled up. I really thought that the end was coming and prayed for the Allies to win. I was slowly getting short of breath. In no time, I heard English voices, so called out to them and a soldier cried out: "She speaks English." I explained where Masha was from where I was. The soldier had found my arm and held it so as not to lose the spot where I was. Masha had a cut on a shin and I had a few small ones on my head. The British Medical Officer was very kind and saw to Masha's cut. Eventually we were offered rooms in a flat. The husband was a French Algerian lawyer and his wife the head of the Girl Guides whom we knew.

The French Protestant Church, L'Eglise Reformee de France, buried my family, Helene together with her father, as there was a shortage of wood.

Eventually, Misha who had a scholarship to a boarding school in Bone, continued his schooling, as did Masha. They were then 15 and 12 respectively. I heard from one of George's brothers with a teenage son who lived in Paris. He suggested having Misha and Masha. I accepted as it was the best for them, being French with a French education, we would not be remaining in Algeria. I would be returning to England.

The Ponts et Chaussees where George had worked offered me a job as interpreter and telephonist that they needed, as by then they were in contact with the British and American forces. I dealt with the correspondence, also accompanying the engineers when they went out to the British and American air fields.

One day I was told that two British officers were downstairs. One was Colin Lindsay, the son of Lionel and Yone Lindsay I got to know when I went to King's in 1925. The other was Sandy Smith, the 1st Lieutenant of a minesweeper, the Unst, in for repairs. The repairs were done and they left. The crew of the Unst never thought they would return to Philippeville, but they did and I saw Sandy Smith (the future Granpa) once more. It was during the first week of 1943 that I was invited to the Royal Navy New Year cocktail party in their offices at the Harbour.

I was struck by Granpa's good French but thought he must be overworked as his nails were black (pipe ash in his pockets). His captain was a Mr Smith who invited me on board a few days later. My first present to Granpa was a bunch of garlic and he gave me a cake of toilet soap.

A few days later, the Unst left for Malta. They carried on to Greece where they started sweeping mines to open up safe channels between the islands.

It was 1945, peace was in sight. Communications between France and Algeria were easier. French orphans had started to be evacuated back to France. The turn of Misha and Masha came and they sailed to Marseilles, then travelled on to Paris to their uncle.

After the departure of the Unst, Granpa and I started to correspond regularly. This lasted for two years. We got to know each other and like each other. Now left on my own, my wish was to return to England. I would have to move to Algiers to get a boat back. I applied for a transfer which was accepted. In Algiers, rooms had been requisitioned by the British Army for their civilians and I was given one in the centre of town. My landlady was quite pleasant. I was also entitled to have my meals at the British Civilian Mess. It was run by a sergeant, a Jew who used to show me pieces of jewellery he had bought off unsuspecting people, reselling them at a good profit.

Algiers is very hot in the summer so at lunch time I came back to the flat to have a sponge down in the bathroom that the landlady had polished that morning. One day she turned to me and said: "Madame, you are like a duck!" I had splashed her polished taps! After office hours, I went to the Poste Restante to see if Granpa had written; it was a lovely Moorish building built by the French at the turn of the century.

I was the only foreigner ever to have been employed by the Ministry of the Ponts et Chaussees. I was to be employed until my services were no longer needed. Once in Algiers, I made myself known to the British Ministry of Transport so as to get a passage back to the UK. A few merchant ships had started sailing and meanwhile I worked away at my office. Everyone was very nice and I made some friends. But there were no more outings to the air fields.

In the autumn of 1945, I was informed that a passage had been reserved for me to England and I gave in my notice at the office, which was accepted. I left on a Norwegian cargo boat carrying iron ore to Workington. There were two young newly weds in the two available cabins; mine belonged to one of the mates who was absent. The crew was made up of several nationalities and they managed to communicate with each other by speaking to the ones whose language had words resembling their own. The meals were Norwegian with delicious fish balls. The ship had been away from home for four years and the captain was looking forward to seeing his wife who was meeting him in Workington. He had a whole lot of presents he had collected for her on his trips. The first night when I was getting to bed, I heard a sound round my feet as if I had dropped a belt. When I looked down, I found a rat rushing around trying to get away. One of the crew helped me to chase him out.

The journey took about three weeks. We arrived in Workington in the dark. The sight of a bobby after eight years absence was a pleasant one. The moment the engine came to a standstill, the crew were free to leave the ship, all the lights went out and we, the passengers, were left in darkness. Some kind person helped me to take my trunk ashore and I left by train for London. I must have had a permit as I had no English money. Joanie's elder sister lived in north London and was warned by her of my arrival. Granpa arrived on the same day as me from Marseilles (south of France). He got in touch with Joanie in Cornwall and left his address – a room in a requisitioned hotel behind Victoria Station. He somehow knew that his parents were in London, he gave me their address on the phone. The following day we met there. I was in the only clothes I possessed, he in uniform, fresh from the barber's. Great Granny was in bed with flu. So I first saw Granniepapa (as he called himself after Andrew was born) coming down the stairs to meet me. He took me up to meet her. They left for Crowmallie soon after and Granpa and I took the train for Cornwall. He did not feel that he wanted a big wedding with guests he had not seen for years. So we had a quiet one with Joanie's husband giving me away. It was at Paul Church outside Penzance, not far from Lamorna where they lived. It was on the 15th December 1945.

We left for Crowmallie just before Christmas. We hadn't been there longer than a week when the phone went, ordering Granpa to report to the office for duties near Southampton. We found a room in a private house in Hamble, near the office. I could hear the ships' horns in Southampton harbour. Granpa, in uniform, left every morning on foot, soon after 8am, to his office, which was in a requisitioned private house down the road. After a few weeks he was demobilised, given a suit and a lightweight coat, and we set off to London to Gogo and Di's flat. They had a maid, so we were very comfortable. Andrew was on the way, and I longed for drinks of Bovril! Gogo was away on a destroyer where he was 1st Lieutenant, Di was at Crowmallie. Waiting for Andrew, we finished up in furnished rooms. Just before that, we decided to visit Papy, Mimi and Helene who were then in Paris where Helene was dancing. There I became unwell and the French doctor sent me to the British Hospital. The ward was full of British patients who had at one time either worked in France and settled there, or married Frenchmen. Feeling better, we set off for Chantilly, near Paris, known for its lace. It was a lovely spot near a forest and we took drives in a horse drawn carriage. When at last I felt stronger, Granpa got flights for us through Thomas Cook's Travel Agents in Paris. We flew from Le Bourget to Croydon (Heathrow had not yet been built). The stewardess announced that the pilot had flown many thousands of miles and that the first aid box was well equipped! Grannypapa had organised an ambulance. We were taken to Gogo and Di's flat. We eventually found furnished rooms and we settled down to wait for Andrew. Granpa decided to take lessons in Russian and went daily to the Berlitz School.

The day came when I was to be admitted to Mandeville Nursing Home, near Harley Street, and Andrew was born the following night, 31 October 1946. He was the first grandchild and there was great excitement at Crowmallie expecting us.

We stayed at Crowmallie a few months. At that time a university friend of Granpa's suggested we engage a Swiss nanny for Andrew, and just to please him we accepted. She was a pleasant very tall young woman in her 20s from Zurich. I would have preferred looking after him myself but we kept her a few months.

As Granpa was keen to have an occupation, he decided to buy a fishing boat, the Village Maid. He started his fisherman's life in Portmahomac, not far from Tain on the Moray Firth. We had a room over a grocer's shop. Annaliza and Andrew remained at Crowmallie and I spent alternate weekends with them. Through friends who lived in the region, we were offered a cottage in Embo, a tiny village nearby, and Annaliza and Andrew joined us. Embo cottage had a bathroom, the only one in the village. At night, sheep and lambs used to cross from one field to the next, making a lot of noise looking for each other.

Granpa had a fishmonger who sold his fish for him, and who was determined to find us a bigger house to live in. His name was Ernie Stout. He heard that Knockbreck House was for sale and suggested we should bid for it, which we did. That is how we acquired it. By then, Annaliza had returned to Switzerland, not without shedding a tear because she had become very fond of Andrew.

Knockbreck House was an 18th century house built by an Edinburgh architect and it was situated a short distance from Tain. It had a short drive leading to the main road north. From the bathroom window, one could see Dunrobin Castle in the far distance over the Firth. We moved in in May 1948. We found it very spacious after our tiny cottage at Embo. It was a lovely happy house. When Va (Eleanor-Violet Jauncey) came to stay, her bedroom was on the top floor. She said she felt the presence of a kindly lady. None of us did.

It was the following November 2nd, that Bob was born in the front spare bedroom on the first floor. I had a midwife who stayed ten days. At that time, Mimi and Papi came to stay with us. Mimi took Andrew for walks and Papi took over the cooking. When Andrew and Bob were small, Knockbreck was an ideal place. They spent hours playing with their Dinky toys in front of the house or up and down the drive with their tricycles, or down towards the walled garden and the gardener's cottage.

As the boys grew, we felt that the main road was too close for cycling. There was also the question of schooling.

In 1957, Grannipapa died and Great Granni decided to divide Crowmallie between Gogo and Granpa. We had a kitchen built on into the yard, a bathroom on the top floor and a staircase to the first floor. We moved in in 1958 and were nearer to relations and friends.

Time had come for Andrew to go to school, and Bob followed two years later. They first boarded at Wester Elchies above the Spey, near Craigellachie, aged 11, to Aberlour across the river, then finally to Gordonstoun. They left, Andrew in 1964 and Bob in 1966.

Having visited Corsica from the sea, I decided that it would be so nice to do it by land. So in 1966, when Andrew was 19 and allowed to drive, we set off, that is myself, Bob, Jeremy Quin and Martin Robinson (school friends), from Crowmallie. Helene joined us from Monte Carlo. We crossed over from Nice to Calvi. Granpa joined us later in Ajaccio, as Great Granny had not been well, sailing from Marseilles. The trip was great fun. We had no tents and relied on the lovely weather. Everyone had a job when setting up camp and leaving. Helene and Jeremy buried the rubbish. We motored all the way down to Bonifacio following the road in the west. We returned north up the east side of the island to Bastia from where we sailed back to Nice. There we spent the night in a flat belonging to one of Helene's friends.

Andrew became interested in farming and started working with Jim Steven at Craigmill, the home farm. Soon after, Pitbee became vacant so he asked his uncle Gogo if he could rent it. Gogo accepted and in 1968, Andrew bought it.

Bob and I went on living at Crowmallie. The motor club in Aberdeen was a great attraction. Both Andrew and Bob won many cups. They both became North-East champions.

Galena was built in Buckie in 1967. That same year Granpa and Bob visited the Orkneys in her. It was the following year – 1968 – that Granpa, Willie the deckhand, and Bob undertook the long trip to Malta. They sailed down the west coast and crossed over the Cherbourg from Poole. That was in May.

Jeremy Quin, Alice Troup and I joined Galena south of Paris, along with Helene and Walter; this was at La Roche Migenne. Willie the deck hand left for the UK from there. Papi and Mimi with their two dogs had just gone home. Then visitors came and went at intervals: Martin Robinson, Rosemary Jones, Maya Trotsky and her two, Aliosha and Sandra.

It was a most interesting journey through the French canals and rivers, all the way down the Rhone to Saint-Louis near Marseilles. We carried on east, hugging the Italian coast. Maya and her two left us at Imperia, near the Franco-Italian frontier, to return to Belgium. They were the last visitors on Galena, leaving Granpa, Bob and myself with Jeremy to carry on to Malta. On our way, we visited the famous Carrara Marble quarry. I believe that East Crowmallie drawing-room mantle piece is made of it.

We had a most interesting and exciting night off Stromboli volcano sheltering us from the easterly wind. It is not far north of the tip of Italy and the Sicilian coast. It is an active volcano erupting constantly like a giant firework with the ashes falling still alight into the sea. It was pretty hot, even Galena's water in the tank was warm. At 4am, Granpa decided we could proceed and at 11am, we were having a lovely swim off Messina in Sicily, just off the tip of Italy.

The last stage of the great enterprise from Sicily to Malta was sunny but very windy and rough. I became worried with the pitching and tossing. I sat in the saloon counting the waves, the seventh always the largest. I was convinced that we were heading for Tunis, but Bob came down to announce that they had sighted Malta. It took us four hours to reach the island and entering Valetta we left the pitching and tossing behind.

During her six year stay in Malta, Galena sailed several times to Corfu and Greece.

In June 1974, Granpa brought her back as far as Sete, some distance west of the Camargue. There Andrew, Bob and Janey brought her back through the Canal du Midi, along the Atlantic coast of France and the west coast of Scotland to Buckie. Tom (Pittodrie), Muriel and Bill Rumbles joined for the sail through the Canal du Midi.

When Andrew and Bob were at school, I did a lot of travelling. My guests for the various trips were Joanie Evans, Maya, No.1 Di or Helene. We visited Portugal, the USSR, Italy, France, Switzerland, Morocco and the USA, the latter with Helene. We sailed on the SS New Amsterdam, returning by the Queen Elizabeth.

In 1970, Robin Buchanan Smith kindly invited me to the Passion Play in Oberammergau, Bavaria, Germany. The two day stay was very well organised. The tourists who came slept in private houses. Little boys met the buses and took the people to the addresses that had been given with the tickets. The play was quite unforgettable. Jesus, Mary and the disciples were acted by inhabitants of the village of Oberammergau.

In 1971, Andrew married Anne at the Chapel of Garioch on 28 July. A marquee had been erected on the lawn at Crowmallie in case of rain, but as it happened we had glorious sunshine and the guests sheltered themselves in it from the heat.

On 29 December 1975, we all set off for Malta from Heathrow for Bob and Janey's wedding. We had a lovely party on New Year's Eve, celebrating New Year's Day twice – once British time with Big Ben then again with Maltese time one hour later.

Bob and Janey were married in Mdina and left for Kenya for three weeks. The marriage took place on 3 January 1976.

Pamela at that time was 2 years 5 months old and behaved very well. When Bob entered the church she exclaimed in a loud voice: "Uncle Bob!" We stayed in Andrew's villa; Pamela used to stand on the sofa and look out of the window, watching the carts with vegetables go by and calling out: "Neeps, neeps!" She always took off her dress when she came in. Pamela was followed by Kate, then Lorna, Suni and finally Morag.

My life was filled with warmth. You all know the rest.

Pitbee Cottages, July 1990