The Making of the Port Eliot Estate: 18th-Century Finances

Having been largely passed over and forgotten, the 18th-century Eliots are particularly intriguing. It is thanks to the Eliot families of this era that the family rose to their political and social influence of the following century, but the identities of the few individuals who are remembered are always confused with one another and/or misidentified by researchers. No one seems able to sort out just which Edward Eliot was raised to the Peerage in 1784, or who married the sister of William Pitt, or whose mother was the natural daughter of James Craggs. Sorting all of these facts and people out always goes right back to one interesting topic: The Eliot Finances of the 18th Century.

The solution to the mystery of the early Eliot state of affairs lies in the wills, letters and notes of all persons connected to the family during those early years (not just the Eliots).On the surface, the early Eliots appear to be quite wealthy. The family travelled between their country estate of Port Eliot and different London properties, attended court functions, served in prominent government and diplomatic positions, and married into some of the most influential families of the period. Dig a little deeper, though, and you discover that the Eliot's finances were often stretched, at times almost to the breaking point. As the saying goes, they were "land poor". The early Eliots of Port Eliot owned a large estate, but they lacked the money to finance improvements to their house and land.

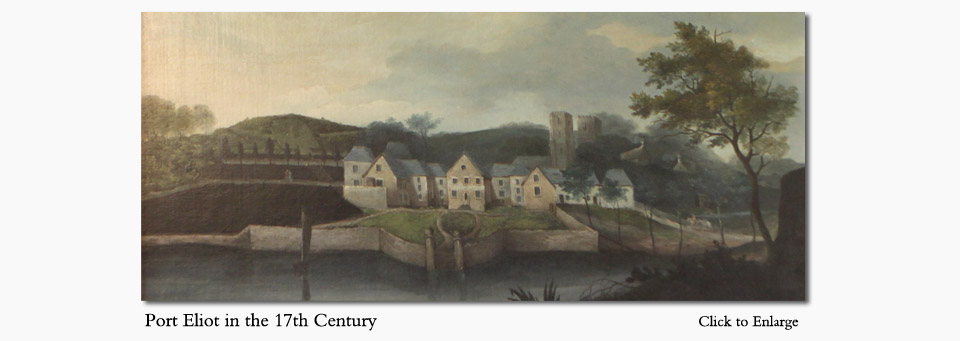

When Richard Eliot (the second Eliot to own the estate and father of Sir John) inherited the estate in 1577, it was worth about £300 per annum. By the time of Daniel Eliot's death in 1702, the same estate was valued at nearly £3,000 per annum, marking the beginning of earnest improvements to Port Eliot and the family purse. The subsequent hundred years proved the making of the estate, culminating in the massive renovation of the house by Sir John Soane in 1804.

The value of the Port Eliot estate continued to grow steadily throughout the nineteenth century. During this period, the Eliots could finally claim an annual income greater than their annual expenditure. They were influential in their town and in politics. They maintained property and estates in Cornwall, Kent, Gloucestershire and London. They employed scores of servants (60 in their heyday), supported the local poor, and were very active in their local community. While the estate may have reached its financial peak in the mid-twentieth century as far as overall ledger value goes, the latter half of the nineteenth century was certainly the zenith of the Eliot "dynasty".

Edward Eliot of Port Eliot (1702-1722)

Daniel Eliot bequeathed Port Eliot and the Cornwall estate to Edward Eliot (the under-age son of his cousin, William Eliot of Lewannick), taking charge of young Edward's education and maintenance. This was an interesting choice, considering the amount of male relatives who were passed over in order that Edward should inherit the estate. Daniel Eliot's only child was a daughter, Katherine, and it was stipulated in Daniel's will that Edward must take her as a bride in order to gain Port Eliot. After Daniel's death, however, Katherine married the famed historian, Browne Willis, instead of her cousin Edward. A family story states that Daniel intended to leave the estate to a closer relative (obviously the Eliot cousins of Trebursey), but that on one occasion, upon leaving Port Eliot for his own home, this relative had glanced behind him at the house. Daniel took this to mean that the gentleman planned on making changes to the house and property. Not wanting anything changed, Daniel took immediate steps to change his will in favor of his cousin's young son, Edward. An entailment on the property, which is still in effect today, was also established at that time.

Daniel died in 1702, at which time Edward Eliot was about nineteen years old. His newly inherited Cornish estate, with properties and incomes included, was far from the flourishing estate and vast holdings to come. The house was little more than a converted Priory, with boxy rooms and no proper lawn. To make matters even more difficult, Daniel's daughter contested the will and claimed the estate for herself. After a legal battle in the same year, Edward was ordered by the court to settle a sum of some £4,500 on his cousin Katherine Eliot (later wife of Browne Willis). Edward's finances at this time, however, appear to have been insufficient to lay out this sum. So, a marriage settlement was written in 1711, in which it was agreed that Edward's future father-in-law (Sir William Coryton) would pay £3,000 of his daughter's dowry to Browne & Katherine Willis. Payment of the balance was achieved by the surrender of part of the Port Eliot estate, under lease for the lives of Katherine Willis, Edward Eliot and his younger brother, Richard.

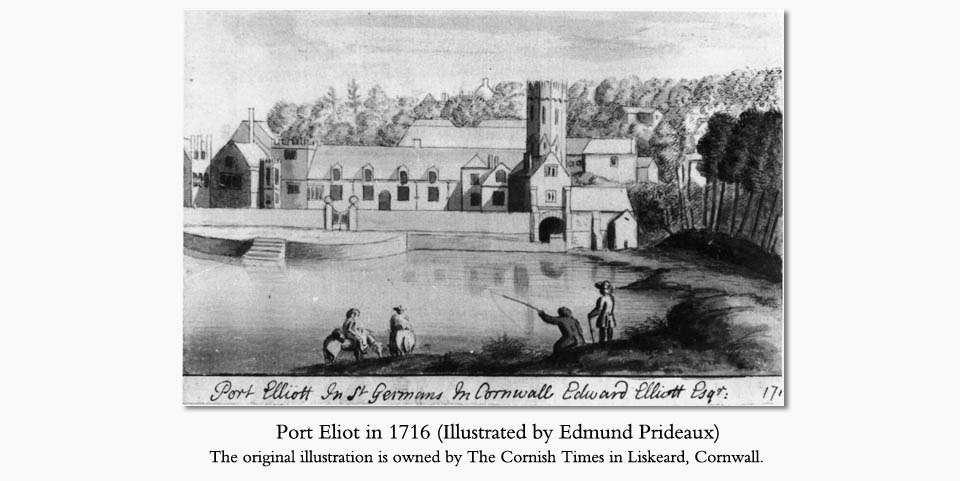

The first major eighteenth-century improvement to Port Eliot was recorded as Edward's construction of "a handsome stone pier", which formed a lawn between the river and the formal gardens on the North side of the house. The result was painted in 1716 (the very year of the pier construction) by Edmund Prideaux, a distant relative of the family.

At the time of his early death in 1722, Edward was in the process of establishing a parochial library, and, though he left an endowment for the purchase of books, it does not appear that his vision was ever fulfilled. It was also at this time that the town of Liskeard came under the influence of the family, becoming a pocket borough of Port Eliot. While this added revenue and parliamentary power (Liskeard sent two representatives to the House of Commons) to the Eliot's estate, it became a serious financial drain on the estate which lasted a hundred years.

James Eliot of Port Eliot (1722-1742)

Edward Eliot died, intestate, at the age of thirty-nine, leaving a young widow and two infant children. His son, James, was only seventeen months old when he inherited the Port Eliot estate. Business matters were handled by the boy's mother and his paternal uncle, Richard Eliot. James' mother, Elizabeth (daughter and coheir of James Craggs the Elder), had a very large fortune in her own right, but there is no evidence of any alterations or improvements made to the estate over the next twenty years. James spent most of his life either away at school or in London. His Mother lived at Port Eliot until about 1729, at which time Richard Eliot moved in with his growing family and Elizabeth moved to London. James died unexpectedly in 1742, unmarried and childless, just six months after reaching his majority.

Through the entailment set up by Daniel Eliot, the estate passed to Richard. This was the first of what would be a long string of younger sons inheriting, a problem which would plague the family at Port Eliot for the next 200 years. Beginning with Richard in 1742 and ending with Montague, 10th Earl of St. Germans, in 1942, seven of the ten owners of Port Eliot during these two centuries were younger sons who had been raised with little or no expectation of inheriting. Although Richard had assisted with the estate matters for years, the thought of inheriting from a young and healthy nephew must certainly have never crossed his mind.

Richard Eliot of Port Eliot (1742-1748)

It is during Richard's time as owner of Port Eliot that the greatest evidence of the family's financial difficulty comes to light, illustrated through the family's own words, in the collection of letters at the Cornwall Record Office. In 1726, Richard had married Harriot Craggs, the natural daughter of James Craggs the Younger and niece of Elizabeth, Richard's previously mentioned sister-in-law. Harriot brought what was termed as a "large" and "immense" fortune to her marriage, but (despite his wife's fortune and the income made from his various diplomatic and political posts) Richard still did not have enough money to support (let alone expand) the Port Eliot estate.

The first written evidence of the family's financial situation is seen in a letter from Richard, dated 23 Nov 1746. He encouraged his oldest son, Edward (who was on the Continent for a "Grand Tour" of study), to make the most of his time and studies, saying that, although he would one day inherit the estate, that that was only one step towards a successful future. Richard continued by saying that the estate was "not of that value the world generally esteems it", and that the costs of living expenses and estate charges had forced him to "put a stop to the Grotto and other schemes". He admitted that this had "greatly contributed to the melancholy looks, which with Filial duty, you have observed to me".

Edward's reply to his father's letter arrived the following month, full of assurances that he was doing all he could to travel as inexpensively as possible. He wrote, "I am heartily sorry your estate does not answer your expectations, nor bring in as much as the world thinks it does. I solemnly promise [to be as frugal as possible], more on account of you, Sir, and the rest of the family (whose well being I hope I shall ever prefer to my own), than for my own particular sake." He promised to send his father an exact account of necessary expenses (e.g. board, servant, masters, etc.) every time a change or move should arise, asking his father to judge if he had been extravagant in any way.

One month later, in January 1747, Edward wrote to his father in need of funds. His request came in the form of an apology: "I am really sorry to be so obliged to ask for any money. I wish from my soul I could do without it, or at least with less." These financial pressures continued to weigh on the mind of young Edward, as illustrated in another letter dated 24 Jan 1747, when he wrote to his father saying, "I write these few lines to inquire after your health, and to ask pardon for a thing that I had done before your letter recommending Economy to me in so very strong a manner reached my hands. Arquebusade Water, I have heard, is the best thing in the world for all cuts, wounds, bruises, etc. It outdoes Fryars Balsam prodigiously. This is the country where it is made and sold cheap. And in England it is a vast curiosity and hardly to be got for love or money. As I thought this would please some of my Relations and friends, and likewise might really be of very great service to them, I remembered to send a dozen little bottles to Mrs. Nugent, Mrs.Booth & my aunt Eliot. I have sent, likewise, a little box full to my mother, and a lesser one to Capt. Hamilton. . . . Now that I have received your letter of the 21st of November, I really begin to fear I have done wrong, and that I may possibly incur your displeasure, which gives me a great deal of uneasiness. I do protest that I never should have sent home any little idle curiosity, which I thought would be only ornamental or pretty and of no use, but this is quite different."

Richard Eliot responded immediately to his son's letter, applauding him for "thinking so rightly of your friends and for the useful present sent them". He explained that he was very aware how young people who had been "brought up with too high and pleasing (the deluding) notions of their Parents' Fortunes" often came to grief and so had felt it his duty to inform his son of the financial state of affairs. He goes on to assure Edward that he has so high an opinion of his son's good sense and prudence "that you may depend on being supplied to the utmost of my power with what cash you think necessary to make you that complete Scholar and Gentleman".

Two months later, in March 1747/48, Richard Eliot had promised his son a further £200 to finance his studies and daily expenses in Europe for the next year. Edward responded with sincere thanks, though he doubted that the sum would last him longer than nine or ten months. He assured his father that he would do his best to live on the £200, as he did not want to deprive any of his family at home. This subject was a common topic in each succeeding letter over the following five months, and Edward expressed his regret at the necessity of mentioning these worries and requests for money, saying "It is an interruption to the happiness of our correspondence."

While Richard's finances were, indeed, stretched, he was yet able to accomplish some major improvements on the estate — despite some postponements and setbacks. It seems that he was merely taking advantage of the state of affairs to train his son in frugality and care of the estate, knowing that Edward would very soon be master of Port Eliot.

Another drain on the Eliot finances was Richard's position as Receiver General of the Duchy of Cornwall. He held this post, valued at about £500 per annum, for each of the last ten years of his life. Despite the honor of the position, it cost more money than it made, causing severe strain to the Eliot purse. In the end, Richard's wife stated that the position had cost them £7,000 and was "the source of all our present woes, yea even of his death, I do believe." Since Edward Eliot went on to serve in this capacity for over fifty years, it must be presumed that the family finances were in better shape than supposed or that the position itself changed for the better.

By the early Summer of 1748, Richard realized that his death was approaching and wrote to call his son home to England (asking that Edward arrive by July) to "settle our family affairs for the general good of all of us by preventing Port Eliot Estate to another family, whilst we have heirs of our own descended from us". This wording is a bit of a mystery, since Port Eliot had already been entailed through the male line by Daniel Eliot. Richard must have been referring to more recent additions to the estate that were not yet included in any will or entailment. Edward returned to Cornwall, setting out with his father for London in the early part of November. Richard Eliot barely survived the trip and died on 19 Nov 1748, just a few days after arriving in the City. Richard died intestate, leaving Edward (as oldest son and heir) as administrator of the estate. Young Edward Eliot, just four months past his twenty-first birthday, was now the head of the family and the struggling estate.

Edward Eliot, 1st Lord Eliot (1748-1804)

Edward took over his father's parliamentary seat as M.P. for St. Germans in December 1748 and in June of 1751 was appointed Receiver-General of the Duchy of Cornwall. Richard had left a lot of debts for his son to pay, but Edward managed to pay them all before the summer of 1751. The well-learned lessons of frugality during his study on the continent, combined with a personality naturally inclined to parsimony, would serve Edward and the estate well in the following decades. While his parsimonious nature could be seen (and often was) as a general character flaw, Edward did manage to accomplish more for the estate than any Eliot before him.

In 1756, he married Catherine Elliston, an extremely wealthy heiress who brought a fortune of more than £60,000 to her marriage. The estate began to flourish under Edward's hands, and he was able to make substantial improvements to the house and property, as well as purchasing large portions of land in the surrounding parishes of Cornwall. He was able to send all three of his sons to Cambridge University and establish them in various political, legal and diplomatic positions, appearing, by all accounts to suffer from no more financial troubles. He was also granted a peerage, being created Baron Eliot in January of 1784.

There was one last major financial "scene", however, in the life of the family at Port Eliot, which took place in August 1785. Edward's oldest son, Edward James, was soon to marry Lady Harriot Pitt. Lord Eliot was disappointed in his son's choice of a bride possessed of neither fortune nor dowry, though he actually liked Harriot personally. Edward James travelled to Port Eliot, in order to discuss the upcoming marriage with his father. Their ensuing conversation was described in a letter (written by Edward James that same night) to Harriot in London. He began by saying that his father told him "with a good deal of agitation, that he already had annual expenses beyond his annual income. That, therefore, it was altogether out of his power to give me any assistance. That he almost desponded of his own affairs and thought it little less than absolute Ruin for us to think of going on on the present plan in the present circumstances, concluding with putting it to me in the most earnest manner and with the most pressing instances . . . not to conclude (or rather to delay concluding) this engagement till Lord Nugent's death or some other circumstance should enable him to do as he should wish to do upon that occasion."

A week later, Edward James (now back in London) wrote to his father to inform him that the marriage was to go ahead as planned. He apologized, saying, "It is no small additional anxiety to me to reflect on the inconveniences of a different kind which you feel yourself in, but which, as some consolation to myself, it is my firmest resolution never to multiply or augment." True to his word, Edward James never imposed upon his father for monetary support, and the father-son relationship was eventually restored to its former state of affection.

While Edward had already achieved many of his alterations and improvements, the estate was still not able to do more than maintain itself. The costs incurred by election and borough expenses were still escalating at a faster rate than incoming profits, illustrated in a letter written by Edward to William Pitt in October 1797: "In election transactions I have never received what in the one town or the other I had not previously laid out. Such receipts were matters of necessity—I have never submitted to them without a feeling of reluctance. Often I have received nothing, and not infrequently have thereby suffered very considerable personal inconvenience." The pocket borough of Liskeard appears to have been the biggest monetary drain in Edward's political career, but it would take several years before it could be sold off. This is the last evidence of the Eliots having what must have seemed like insurmountable financial difficulties, marking an end to the constant money struggles.

The Craggs Estate and Port Eliot

Edward's earlier reference to his son about Lord Nugent's death supplies the key to the solution of the Eliots' long-lasting financial worries. Even though Catherine Elliston's fortune was the largest ever recorded for an Eliot bride, it was not enough to solve the continual Eliot problem: annual expenditure greater than annual income. From the outside, Port Eliot appeared to be a grand old mansion house, but inside it still bore remarkable resemblance to the Augustinian Priory that it had been for centuries. Sadly for Edward, who desired to turn this building into a grand home, the estate could not support the necessary renovations. Through careful accounts and good investment, Edward had been able to achieve some of his desired work, but more money was needed to complete the work.

The answer to Edward's difficulties came from an unexpected quarter: the inheritance of the Craggs estate. This eventual inheritance happened gradually, over more than five decades, and came to the Eliots through a series of unexpected deaths.

The Craggs fortune was . . . vast! It consisted of the estate of James Craggs the Elder and his only adult son, James Craggs the Younger. Father and son both died intestate, exactly one month apart in 1721, and their property and money was divided equally between the three surviving daughters of James Craggs, Senior. The exact amount of the estate is unknown, since there are no estate papers or wills to document particular sums. Craggs the Elder was heavily involved and convicted in the South Sea Bubble scandal, as a result of which Parliament ordered that the executors of the estate refund the £69,000 which Craggs had realized from his fraudulent transactions. (Interestingly enough, Craggs the Younger was not convicted of fraud and did not benefit by funds from the scandal, so his estate went to his sisters untouched.) Estimates of the value of various portions of the estate were printed in newspapers around the country. A fair representation of the estate of Craggs the Elder (divided between his three daughters) was reported to have been £12,000 per annum in Lands (most of it purchased shortly before Craggs' death), £92,000 in South Sea stock, £43,000 in East India stock and £26,000 in Bank stock. The failed scheme was the "hot news of the day", however, and reports were often as misleading and comically erroneous as they are in our present time. The "Ipswich Journal", for instance, went so far as to publish the exaggerated statement that "upwards of 900,000 pounds in Bank Notes, India Bonds, &c. were found in Mr. Craggs's Closet immediately after his Soul was divorced from his Body."

Understanding just how the Craggs property was divided is difficult, since there are no surviving wills from either of the Craggs men or two of the three daughters and co-heirs. James Craggs the Younger's acknowledged natural daughter, Harriot, was given a large share of her father's estate, but this must have been done privately through the beneficence of her three aunts, since she had no legal right to her father's fortune.

The three Craggs sisters (Anne, Margaret and Elizabeth) remained very close throughout their lives, and the estate of their father was split evenly between them. Anne married three times, raising together her one surviving child (James Newsham, from her first marriage) and her brother's natural daughter, Harriot. Margaret had one child, a daughter who died at the age of four years. Elizabeth had two children, James and Elizabeth, but neither survived to have children of their own, both dying in the lifetime of their mother.

Margaret was the first of the three sisters to pass away, dying in 1734 without surviving children. No will is known to exist for Dame Margaret Cotton, but the fact that she left her third part of the Craggs estate to her two sisters is recorded in documents written by her sister, Elizabeth Eliot.

In 1765, Anne departed this life, having vested her moiety with trustees for diverse uses in which her son had an interest. The remainder was left to the lifetime use of her third husband, Lord Nugent, and then intail to the children of Richard Eliot and Harriot Craggs (in order of birth, male followed by female).

Elizabeth Eliot remained a widow, following her husband's early death in 1722, and signed her will in 1760 (with two codicils dated the following year). Quite a lengthy document, it gives an interesting portrait of Elizabeth and her relationship with her nephew, James Newsham. She left all of her property and estates in the care of trustees, directing that they supply him with an income throughout his life. If he were to marry and beget lawful children, those children were to inherit the same properties and money on the death of their father, but she made it very clear that James was never to be allowed to touch any kind of principal or do anything with property from her estate at any time during his life. She loved her nephew because he was the only son of her sister, but she recognized him for the profligate man that he was. In short, she entailed the estate, first to any lawful sons of James Newsham, then to any lawful daughters. If he were to have no lawful children, then the estate was entailed to Edward Eliot (son of Richard Eliot and Harriot Craggs) and his children.

James Newsham did live to marry, but he did not have any children. In fact, his marriage seems to have been rather short-lived, since his bride went back to her father's house in Kent, and James was living with another woman at a hotel in France at the time of his death. He died in November 1769, which means that it was at this time that Edward Eliot of Port Eliot inherited his Aunt Elizabeth's moiety of the Craggs estate, which included her third plus half of Margaret's third (Margaret having passed away first, as mentioned above). This inheritance generously added to the family's ready funds, enabling Edward to begin rebuilding and renovating a wing at Port Eliot just one year later.

In October of 1788, 67 years after the death of James Craggs the Elder, his son-in-law, Lord Nugent, died. According to Anne Craggs Nugent's will, the second half of the vast Craggs holdings passed on to Lord Eliot of Port Eliot, including (but certainly not limited to) the estates of Down Ampney in Gloucestershire and Kidbrooke in Blackheath, Kent.

In order for all three parts of the Craggs estate to have been bequeathed to the Eliots, it had been necessary for all three daughters of James Craggs, their six husbands and five children to die without heirs. As unlikely as this must have seemed at the time, this is exactly what happened over the course of those 67 years. In compliance with the stipulation in his Aunt Elizabeth's will, Edward Eliot assumed, by sign-manual, the additional surname of Craggs. Each male born or married to one of the three Craggs daughters had taken the name of Craggs but, as mentioned, left no offspring. Though Edward Eliot used the name of Craggs (or Craggs-Eliot) for the remainder of his life, his sons did not choose to change their surname. Well into the nineteenth century, however, the family did continue to quarter the Eliot arms with those of Craggs.

The Zenith of the Eliot Dynasty

Following the inheritance from Lord Nugent in 1788, there is no evidence that the Eliot finances were ever strained again. In fact, through the work of Edward Eliot and his third son, John (1st Earl of St. Germans), the estate flourished and became self-sustaining (aided periodically by advantageous marriages, of course). Edward and John succeeded in remodeling the Port Eliot house and grounds, as well as repairing and maintaining Down Ampney and Kidbrooke. They also seem to have been shrewd real estate investors, adding much to the size and value of the estate. The vision and ceaseless attentions of the first Lord Eliot and the first Earl of St. Germans resulted in an estate which has since supported numerous Eliots, through the centuries and, Lord willing, into the future. It has been more than 250 years since the Eliots have been "land poor", saddled with an estate that had more annual expenditure than income. Hats off to the men who made it possible . . .