Who were the owners of Port Eliot, which of them were Earls, and how were they related?

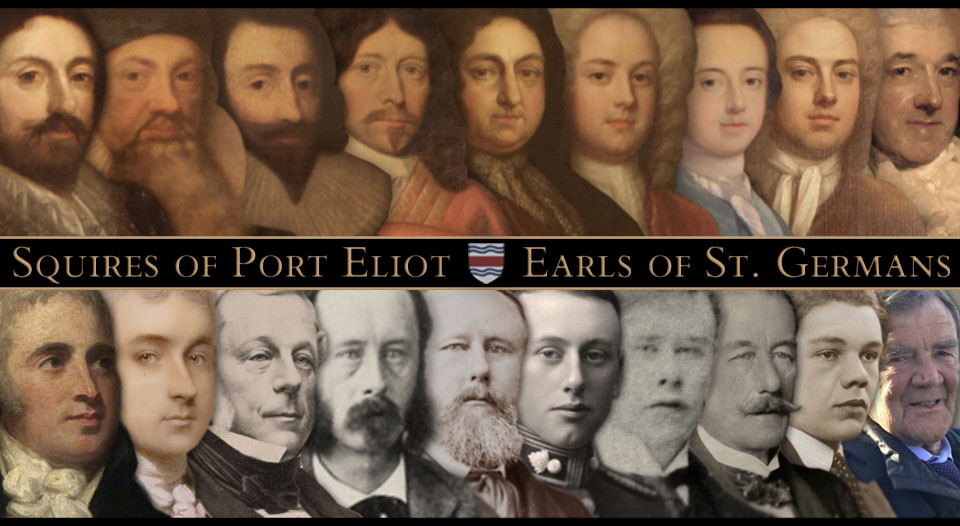

When do 9 + 10 = 450? In Cornwall, of course, at Port Eliot. The banner at the top of this page contains the likenesses of all 19 owners of the estate, in chronological order. Working from left to right, the top row features the pre-Earl "squires" of PE, the bottom row the Earls of St. Germans. This page is dedicated to these 19 Eliot men and the 450 years which they spanned.

Port Eliot first came into the possession of the Eliot family in 1565. King Henry VIII had died just 18 years earlier, the country had since bowed the knee to four different monarchs, and Turbulence alone reigned supreme. When John Eliot of Coteland (great-uncle of Sir John Eliot) purchased the PE estate, "Good Queen Bess" was 32 years old and only seven years into what would be a long and pivotal reign. The priory of St Germans, having been uninhabited for nearly 30 years since the Queen's father had evicted the Augustinians and claimed the once-thriving estate for the crown, bore little resemblance – inside or out – to what is now known as the Port Eliot mansion.

During the first 450 years of Eliot ownership, the house and estate passed through the hands of nineteen male heirs in the one Eliot line. One was a Knight, and ten Earls of St. Germans graced the halls of Port Eliot.

The house has been remodeled, restored, renovated, added to, modernized, closed and opened. Outbuildings have been built and torn down. The estate's original 200 acres have been swelled by later acquisition and estate management to about 12,800 acres and shrunk back to its current state of about 6,000 by personal loss and tax levies. Manors have come and gone, fields cleared, the river moved away from the park, marshes drained, and Sir John Eliot's birthplace demolished. The various owners of Port Eliot have sometimes resided in the house, at other times leasing it out or using it as a holiday refuge. The one thing that remained the same, though, is the fact that one single family line has had unbroken possession of Port Eliot for more than 450 years, and that's a remarkable record.

Understanding the line of succession can be a little confusing, because lines have ended and the entailed estate passed to uncles, cousins and brothers bearing the same Christian names. This page presents the squires of Port Eliot and the Earls of St. Germans (including some of their particular contributions to the estate), continuing through the earldom of Peregrine, 10th Earl of St. Germans, which ended in 2016.

This John Eliot has rightly been called the "founder of the family's fortune," being the first Eliot to leave Devon and settle in Cornwall. Sadly, he has been, more often than not, confused with his nephew and heir, Richard Eliot. But it was not Richard who purchased Port Eliot, it was John.

John Eliot of Coteland was a "gentleman, merchant and mayor" of Plymouth before leasing the manor of Cuddenbeak (some time before 1554) in St. Germans. This provided him with a splendid view of the Champernown's property, the old Augustinian priory standing beside the ancient church of St. German's. In 1565, after more than ten years of looking at this neighbouring acreage, Eliot purchased from Henry Champernown the priory and almost two hundred acres. There is a deed in the Port Eliot collection that records a payment of £500 for the land, but tradition has it that there was a trade of the St. Germans property for Eliot's inherited estate of Coteland in Devon. As John was definitely the last Eliot to live at Coteland, it seems that both the land and money completed this deal.

Now that he had acquired a nice property, John set about turning the old priory into an "attractive and extensive Tudor dwelling". He married twice but died (without issue) on 29 Apr 1577 at Port Eliot, and his estate was left to his wife and his nephew, Richard Eliot. While his will only mentions that his wife had a life interest in Port Eliot as her jointure, biographer Harold Hulme recorded that the mansion, orchards, gardens and some fifty acres had been included in the marriage settlement. After John's death, there is no evidence that she remained in Cornwall, but Richard and his family continued to live on the estate at Cuddenbeake, and the house presumably sat and waited.

Having inherited his uncle's property, Richard Eliot became a well known and loved squire in St. Germans. He lived with his wife at Cuddenbeak, until Port Eliot reverted to him in 1596, after which time they resided in the Port Eliot "mansion".

Richard was known for his "ancient hospitality and generous living", and he was a friend to almost all the neighbouring gentlemen of the area. When it became likely (due to ill health) that he would not live to see his only son attain his majority, Richard spent much of his time preparing his estate and attending the legalities of the wardship of John. This was given to his friend, Richard Gedy of Trebursey (who was also one of the four men to hold Eliot's property in trust until young John came of age). In one last effort to secure the estate, Eliot arranged for his son to marry Gedy's daughter, Radigund.

Richard Eliot died at Port Eliot on 22 Jun 1609, leaving his estate to his seventeen-year-old son, John.

Without a doubt, Sir John Eliot the Patriot was the most influential and renowned member of the Port Eliot family. While his actions brought the family more political renown and social status than had been enjoyed before, he did not have a very active hand on the Port Eliot estate. He married Radigund Gedy in June 1609, and the young couple made their home at Cuddenbeak.

Port Eliot sat empty during most (if not all) of Sir John's life. He leased it to a tenant farmer who farmed the land, but there is no evidence of anyone living in the house. Sir John signed two letters during his life "at" Port Eliot, and he reserved the right (which he exercised) to style himself "of Port Eliot," but that seems to be the extent of his involvement with the house. When he died, the interior inventory, as recorded at the time, describes no more than a series of store rooms filled with the barest of trunks and bedsteads.

Sir John's legacy was certainly more for the good of the country than for his personal estate, but as that deserves a page of its own, we will continue with the simple story of Port Eliot's owners. Once again, the squire (this time being Sir John) faced the certainty that the estate would be left in the hands of a minor. Unfortunately, Sir John died in the Tower in the early morning hours of 28 Nov 1632, before completing the arrangements to secure his son's guardianship by marrying him to the daughter of Sir Daniel Norton. Port Eliot passed to his oldest son, another John, in one of the most financially precarious positions the estate would ever know.

Young John Eliot was eleven months away from his majority at the time of his father's death, leaving him a ward of the court. In an effort to combat the effects this would have on the estate, Sir John Eliot had arranged for his son to marry the daughter of Sir Daniel Norton, a trusted friend. Unfortunately for all involved, the wedding took place on the morning of 28 Nov 1632. What no one outside the tower could possibly have known was that Sir John had passed away in the wee hours of the same morning, causing young John's marriage to be made without the permission of the court of wards. The Norton and Eliot estates were heavily fined, and the following years were tumultuous for the young squire of Port Eliot. (So severely did the estate suffer "at the hands of the Royalists", in fact, that a £7,000 compensation was granted to John Eliot –fifteen years later, in 1647 – by the Long Parliament.)

John Eliot held numerous parliamentary positions, but he was usually listed as inactive. He spent most of his life in Cornwall, with some time in Hampshire (the home of his in-laws). No indication or record has surfaced (at this time) to show whether John actually made his home at Cuddenbeak or Port Eliot. He and his family may have lived in either or both. Without a doubt, though, he was able to pass the estate on in a much better state of being than the one he had inherited. Port Eliot appears to have been financially sound, and it was certainly in good condition as a private residence (if it was not already being used as one).

John died in March of 1685 and was buried in the family vault, under the church floor, on the 25th of that same month. Port Eliot passed to his third (but oldest surviving) son, Daniel, the fifth Eliot to claim possession of the estate.

Daniel Eliot was about forty years old when he inherited Port Eliot from his father. Four months later, Daniel married, and two years after that a daughter was born. This was his only child, and while he made monetary provision for her, leaving the estate to a woman was not in his plans.

Daniel made some of the most lasting decisions for the Port Eliot estate – decisions which have impacted every heir since, all the way into the 21st century. He definitely made Port Eliot his home and lived in some affluence in his home county, being a gentleman "of near three thousand pounds per annum." While Daniel made his home at Port Eliot, his cousin, William Eliot, made a home at Cuddenbeak (then referred to as the family's "Dower House"), and the estate flourished.

At the end of Daniel's life, Port Eliot House had still not changed much since the minor renovations accomplished by the original John Eliot, as evidenced by the abundance of extant rooms, windows and walls dating from the mid-fourteenth century. While Daniel may not have changed the structure very noticeably, though, his ownership would impact the Eliots for generations to come.

Daniel's foremost desire was that the estate should remain in the family name. To this end, he placed an entail on the entire estate in his will (written in 1694). To accomplish this and in the absence of a son of his own, he was forced to choose one of the male descendants of Sir John's other sons, since even all of his own brothers had pre-deceased him. This meant going through the line of either Edward Eliot of Trebursey (Sir John's third son) or Nicholas Eliot of St. Juliot (Sir John's fifth son). Daniel chose the eldest grandson of Nicholas, Edward Eliot, and – when Edward was still a young boy – brought him to his own house, paid for his schooling and raised him as his heir.

An interesting family story, recorded many generations later by the 4th Earl, shows that young Edward was not Daniel's first choice, however. (Presumably, he was thinking of an Eliot from the Trebursey line.) "It is related that the person whom [Daniel] had designated as his heir, on one occasion (when leaving Port Eliot), turned round to take a last look. Mr Eliot conceived [this] to be an indication of his intention to make alterations on succeeding to the property; and, taking offence thereat, altered his will, leaving Port Eliot to his first cousin once removed, Edward Eliot."

To add even more mystery to the story, there was an original stipulation in Daniel's will that young Edward should marry Daniel's daughter, Katherine. There is, however, no further reference to this stipulation in the codicil, and young Edward is made heir with no mention of his marriage to any particular girl. It is this pivotal entailment, shifting the family line into that of the youngest son of Sir John Eliot, that put Port Eliot into the hands of the future Earls of St. Germans.

Daniel Eliot died on 11 Oct 1702, at the age of about fifty six years, and the estate passed to his cousin's young son. (NB Daniel's will was the last one in the Eliot line of descent for a hundred years, the following three squires all dying intestate.)

Edward was only about nineteen years old when he inherited his cousin's estate. Until his 21st birthday, business was conducted by the trustees named in Daniel's will. Edward seems to have been quite up to the task of managing his business, however, and by December 1705 his name appears on legal deeds and parliamentary reports.

Edward was quite active in politics as well as exercising his squire's hand on his home estate. Rooms remaining from the fourteenth century priory were torn out. His real contribution, though, lay in the fact that he was the first Eliot to begin the large-scale battle of clearing the water from the Port Eliot park. In 1716, he caused a large stone pier to be erected. He had many plans for the grounds and estate at large, including an elaborate waterway and dam system to create areas for both fresh and saltwater fish, an ornamental garden, and the establishment of a parochial library at St. Germans. Alas, his sudden death in September of 1722, at the age of only thirty-nine, prevented any of these coming to fruition, and it was left to an infant's care.

Edward had married twice, but it was not until his second marriage that he was blessed with children – a boy and a girl. This son, James, was only sixteen months old when Edward passed away.

At only sixteen months, James Eliot was the youngest heir to the Port Eliot estate in the family history. His mother was one of the daughters of James Craggs the Elder, and she possessed a remarkable business head. As guardian of her son, she oversaw much of the financial end of the running of the estate. She lived at Port Eliot with her young son for several years after Edward's death, but once young James left for school, it appears that she left for London. All of the political business and day-to-day running of the local affairs was looked after by young James' uncle (only surviving brother of Edward), Richard Eliot.

By 1729, Richard and his wife were living "at Port Eliot". They certainly spent time there; but, throughout the 1730s, their home was in another house on the estate (Molenick). Once again, just who was living at Port Eliot during this period is unknown. Perhaps James and his mother used it as a country seat, but young James certainly spent most of his time at school and in London.

In May of 1742, James came of age, and Port Eliot and the local tenantry could once again look forward to an active squire. It did not last, however – James did not even have time to stand for one of the family's parliamentary seats. In November, while still living at his house in London, James caught a cold "by dancing, sitting up too long after it, without taking proper care of himself, then rode near twenty miles the next day, in most violent weather". His cold developed into a fever, and he died at his London home on 24 Nov 1742.

James died intestate, and everything passed (by entailment) to his uncle, Richard Eliot.

Richard Eliot was the first of the Eliots to inherit who could not possibly have imagined that he would one day be squire of the estate. He was forty-eight years old and the father of eight children. He had spent the early years of his career in diplomatic service, later becoming very active in politics and the care of nephew's estate in Cornwall.

While it may have been an unforeseen turning point in his life, Richard was up to the task. He began the process of modernizing and developing Port Eliot and its park into the grand seat that it became in the 19th century. He began the draining of the water from the park, planted trees, made walkways, renovated the house and built "The Craggs" (a magnificent folly on the property) on an old quarry, crowning it with a circular summer house.

Times became difficult for Richard. His finances were under great strain, due to the enormous cost of certain political positions which he held, and the stress took a toll on his health. In the summer of 1748, when it became clear to all that his health would not recover, Richard called his oldest son, Edward, back from his "Grand Tour" on the Continent. Edward had just turned twenty-one, and father and son hurriedly journeyed to London with a box of family documents. All money and property was signed over to Edward at that time, insuring that everything stayed in the family's hands. Directly the work was finished, before there was even time to journey back to Cornwall, Richard died. He was taken back "home" and buried at the St Germans church on 3 Dec 1748.

Edward Eliot is the first of the key figures in the Eliots' rise to affluence and political influence, both in Cornwall and abroad. During his fifty-five years as squire, Edward brought the family estate out of debt, acquired more valuable property, turned the house and park into a fitting seat for their new station of prominence, and exercised more political power in Cornwall than any Eliot before or since.

Edward had purchased and inherited large portions of property, swelling the estate to an impressive size. The Craggs inheritance added the substantial manors of Kidbrooke and Down Ampney, leaving the Eliots in possession of 1-1/2 square miles of Greater London property.

Edward did not love London or city life, and with each passing decade he spent more and more time at Port Eliot. He continually worked on his various renovations and updates, finally effecting the removal of the unsanitary churchyard which stood "just outside the dining room window". He created a formal garden area between Port Eliot and St. German's Church. The 30-acre park was raised by 15-20 feet to bank the river back from the house. (NB The one-way valve installed by Edward before 1804 has only been replaced twice – once in the 19th century and again in 2010, when the 10th Earl was forced to replace the replacement.) One of Repton's now-famous Red Books is a family heirloom at Port Eliot, even though Edward did not hire the landscaper to carry through on any of the suggestions.

Edward was actively interested in agricultural improvement, and he used his own estate for the advancement of the same. (NB He was the first person to introduce the growing of Turnips into the county of Cornwall.)

Edward was the father of four sons. His two elder sons having died in his own lifetime, the Port Eliot estate passed to his third son, John Eliot. He wrote a lengthy will, entailing all of these additional properties to his male heirs. On his death in February 1804, Edward left a financially solvent estate, greatly enlarged and updated by his own diligence and hard work.

John Eliot inherited Port Eliot when he was forty-two years old and ready to pick up where his father left off. He took the already altered estate and continued updating the house, firstly by engaging the renowned architect, Sir John Soane. He also added to his purse (or paid for his alterations to the estate) by selling large amounts of timber for the use of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic wars.

John also continued to be active in politics, even after his inheritance, and it was for his continued support to the ideals of William Pitt that he was created Earl of St. Germans in 1815. He married twice but without children. When he died in November of 1823, his entailed estate and family titles passed to his brother, William.

William inherited at the age of fifty-six, when he had four grown children and was happily married to his fourth wife (having outlived the others). He had been the owner of the Trebursey estate, once the seat of Richard Gedy, for the previous twelve years. After the death of his brother, William moved his family to Port Eliot and sold his house at Trebursey, making Port Eliot his main residence for the rest of his life.

This change in squires marked a new era for the tenants of the estate and the villagers of St. Germans. William was a very benevolent landlord, and a loyalty between the family and the tenants began that was not broken for the next hundred years. William made some great changes to the house in the 1820s by executing not a mere renovation but a "rebuild." He added the first offices, a smoking room, the large kitchen and a complete servants wing (in the process of which the old gallery and music room were razed). As well as accomplishing these great additions to the house, the former Diplomat turned his special brand of attention to creating a loved and revered name throughout Cornwall – for himself and his family to come.

After twenty-one years as a most beloved and honourable squire, William passed away; but not without leaving provision for his one surviving daughter and passing the titles and estates on to his forty-six-year-old son.

Edward inherited a flourishing estate. At the time of his inheritance, the estate was valued with an income of £20,000, and included holdings in Cornwall, London, Gloucestershire and Wiltshire.

It would seem, however, that the family felt some more modernization was necessary. For the several years as owner of the Cornish mansion, those "improvements" were carried out. Family letters from the time infer that great changes were taking place in and out of the house.

Edward was certainly the political pinnacle of his family, considering the many posts he occupied throughout his career (not the least of which was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland). The pre-school portion of their children's youth were divided between Port Eliot and London. Port Eliot was definitely the place to spend Christmas; the autumn leaves drew them every year, and shooting parties at PE became legendary. (NB The vast quantity of game shot during these was typically donated to the village poor and various other charities.)

The death of their second son in November 1854 (during the battle of Inkermann in the Crimean War) so affected the Earl and Countess that they withdrew to Port Eliot for comfort. The Countess survived their loss less than two years, before passing away from the effects of her overwhelming grief. Edward, too, was never the same and retired from public life, spending the last decades of his life at Port Eliot. He was a good master and greatly loved by all the employees and tenants on his estates.

On Edward's death in 1877, the estate and titles passed to his third son, William.

William never expected to inherit the family estates or titles, having two older brothers. Having been trained from a young age for service in the diplomatic field, he spent more than ten years serving in embassies around the world. After their untimely deaths, however, he found himself holding the courtesy title of Lord Eliot and returned home to his native England to embark on a political career. So valued were his opinions, that he was called to the House of Peers as Baron Eliot, in his own right, during the lifetime of his father.

William was considered to be "exceedingly popular" in the neighbourhood of Port Eliot and "always ready to assist any good work", but this seems to have been more in the form of lending his park to various charities for their bazaars and fetes. His brother and sister-in-law lived in the house and kept it running for him. His real delight lay in the Port Eliot estate as a place away from it all, where the memories of his childhood freely roamed. For much of his adult life, he catalogued family history and visited ancestral burial grounds.

Shortly before the death of his father, William (still Lord Eliot) "most pressingly" invited a man to visit him at Port Eliot. In his memoirs, the man recorded, "I went on Saturday. He met me at the station, and I was almost walked off my feet for four hours, being shown every picture in the house, every plant in the garden, and every walk in the woods. There is a limit in what ought to be shown, and Lord Eliot has never found it out." (For what it's worth, this gentleman published his memoirs in three large volumes, obviously not having understood the limits himself.)

William died, unexpectedly and unmarried, at the age of fifty-one — having been Earl for less than three years. The estate and titles passed to his younger brother, Henry.

Henry was, perhaps, the most beloved Earl of St. Germans. Although trained for a career in the Navy from the earliest days, congenital loss of hearing forced him to transfer early on to a Clerkship in the Foreign Office. Unprepared for public life, he little imagined that the role of Earl and squire would fall to him – least of all at the age of 46 years. Nevertheless, Henry assumed the duties of his station and honoured the names and reputations of his most noble father and grandfather before him. During his thirty years as Earl, the estate flourished, reaching the pinnacle of its beauty and local reputation.

Henry was heavily involved in almost every charity and organization for the aid and betterment of others in his beloved St Germans. He also undertook major renovations of the house and the church in the 1880s-1890s (many of them still in place today), creating a thoroughly "modern" home and perfect backdrop for the many balls, parties and social events.

Time had taken its toll on Port Eliot, and Henry spent more of his resources on repair work than additions. (According to Peregrine, 10th Earl, Henry did not repair or add, he RENOVATED.) The one remaining Priory wall had begun to buckle, necessitating that a support wall be built alongside it. During this period, twelve radiators were added to the 100+-room house and bathrooms were most likely modernized. Renovation occurred inside and out, the Orangery was in constant use as a Bazaar area, and the bulk of Henry's mark on the estate was the Victorian reconstruction of the Norman church.

After the sudden death of his 23-year-old son and heir in 1909, Henry's health deteriorated, and he died at the home he loved in September 1911. His estate and titles passed to his only surviving son and heir, John.

John (known as Mousie to his family and friends) inherited the titles and estates just months after his twenty-first birthday. He was an officer in the Royal Scots Greys and, despite his new station, remained with his regiment to serve in the trenches throughout the first World War. The death taxes imposed on him (after the death of his father) were enormous and required that he sell some outlying portions of the family's Down Ampney estate. Throughout the war, the house was used by his mother and was the site of many fundraising events. But the days of fancy balls and parties were over, and the formal garden faded from sight with the lack of men to maintain it.

John returned from the war a hero and married the daughter of the Duke of Beaufort, bringing a young Countess home to Port Eliot. Their main entertainment was hunting and riding, so many horses and dogs were brought to the estate. Modernization was once again needed in the house, so projects were undertaken in 1921 which forced the young family to make their temporary home with his mother at Penmadown (the Dower House and home to the Dowager Countess).

In April of that year, John was severely injured when his horse fell and rolled over him during a local Point-to-Point race. Unfortunately, he never recovered from the ill effects and passed away nearly one year later. John died leaving only two infant daughters, so the entailed estate reverted back to the next male heir in the family line – his first cousin, Granville John Eliot. The death of this "noble Lord" marked the end of an era for the whole village and estate. With the great changes brought about by the two world wars, and the change in ownership, the Earls and tenants never regained the same relationship that had been enjoyed throughout the nineteenth century.

"Jack" (as he was known by family and friends) was the oldest son of Charles Eliot, the sixth and youngest son of the 3rd Earl. He had grown up at Port Eliot, but the inheritance of the estate was certainly a surprise to this branch of the family. Jack had been committed to a mental institute in April of 1921 (a year before his succession to the earldom) and remained there for the rest of his life. Consequently, he never set foot in Port Eliot, or even Cornwall, for the twenty years he was squire and Earl. His affairs were managed by his younger brother, Montague, who moved into Port Eliot at the time of Jack's inheritance. It was to Montague that the estate passed on Jack's death in 1942.

While Montague officially inherited the Port Eliot estate and family titles in 1942, he had been living on the estate and managing its affairs during his brother's time as Earl. This made his time as acting squire a rather staggering thirty-eight years.

The time of great renovation was over, and little was done to the interior or exterior of the house during his time beyond decorating. Because of this, you can still see much of the original 1804-era paint, as well as the 1890s damask wall coverings. Montague continued the ongoing work of cataloging the family paintings, as well as bringing in professionals to clean the most renowned works in the collection.

Montague did not have a good relationship with his oldest son and heir. His grandson, Peregrine, when not at school, resided at Port Eliot with his grandparents. On 21 Sept 1960, Montague, 8th Earl of St Germans, passed away at Port Eliot. The late Earl's will was probated in February and March of 1961.

Nicholas was an Earl of St. Germans, but he was not owner or squire of Port Eliot, since this part of the estate passed directly to his son.

It us unclear whether the 8th Earl's will split the estate or Nicholas did it in his own time. What is clear is that Nicholas retained control of his own portion, apart from any Trustees, comprising the immensely valuable 1-1/2 square miles of London property. Blackheath had belonged to the Eliots for 200 years (part of the Craggs inheritance) and was the primary source of funding for the entire estate. Nicholas held this property for a short time only before selling it off and gambling the proceeds, thus leaving the Port Eliot estate bereft of the necessary income. The rest of the estate, comprising the now-unfunded Port Eliot and other Cornish properties, was placed in a Trust and "gifted" by Nicholas to his son, Peregrine, on the latter's 21st birthday. Nicholas never lived at Port Eliot as Earl, having gone into "tax exile" by making a home for himself in Tangiers, where he died in 1988.

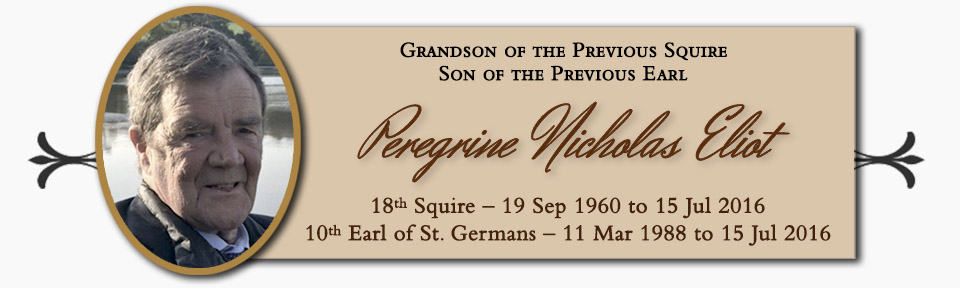

Peregrine, the 10th Earl, was more than two years from his majority when his grandfather died. When he came of age on 02 Jan 1962, in an unprecedented move, his father signed over possession of the Port Eliot mansion and other Cornish properties to Peregrine. He lived there as "King of the Castle" (to use his words) for fifty-six years – the longest time-period in the family history in which one Eliot was the squire of the estate.

While his contributions to the estate included the addition of a maze and other statuary in the grounds, as well as the fairs and festivals for which the property is now known, Peregrine did not undertake many renovations within the house (apart from some bare necessities, such as a lock on the front door). His knowledge of the family history was astounding, however, and Port Eliot was an integral part of his being. He was well-versed on all the intimate details of the house and its past inhabitants and had more than a nodding acquaintance with the art and beautiful furnishings belonging to the estate. He was a "frustrated architect" who knew every detail of the house's structural and landscape history. There was not a room in the house that had escaped his notice. If he was asked if the family possessed a particular historical item (no matter how unusual), his answer was immediate and detailed (usually down to the current location of the item). He was particularly fond of the Naval history of his family and interested in all things having to do with his family's military and royal service. He had read through family diaries and knew the history of the important jewelry pieces and bric-a-brac scattered throughout the living areas at Port Eliot.

Peregrine's counter-culture lifestyle belied the true nature of this aristocratic Englishman. He was, in his heart of hearts, a throwback to the old country squire, who looked on his land and stood a little taller with pride. Before he died, he said that every owner of PE had left a legacy, and he wanted – as his legacy – to leave a Port Eliot Family History book to stand next to the others in the library. As 18th squire of the Port Eliot estate, that's a lot of history, and Peregrine, the 10th Earl of St Germans, is the end of an era that began more than 450 years ago. An era of proud squires whose lives were inextricably bound with the Eliots who had made Port Eliot what it is today. A home with a very long family history.

While Peregrine passed away before his dream of a book was realised, he had laid the foundations for this website and compilation of his family's history. It was his intent that this information be made freely available, in the hopes that his love of the family history and estate would be kept alive for generations to come.